The reporter from Men’s Health asked me: “You finish dinner, even a satisfying low-carb dinner,” — he is a low-carb person himself — “you are sure you ate enough but you are still hungry. What do you do?” I gave him good advice. “Think of a perfectly broiled steak or steamed lobster with butter, some high protein, relatively high fat meal that you usually like. If that doesn’t sound good, you are not hungry. You may want to keep eating. You may want something sweet. You may want to feel something rolling around in your mouth, but you are not hungry. Find something else to do — push-ups are good. If the steak does sound good, you may want to eat. Practically speaking, it’s a good idea to keep hard-boiled eggs, cans of tuna fish around (and, of course, not keep cookies in the house).” I think this is good practical advice. It comes from the satiating effects of protein food sources, or perhaps the non-satiating, or reinforcing effect of carbohydrate. But the more general question is: What is hunger? Read the rest of this entry »

Targeting insulin inhibition as a metabolic therapy in advanced cancer. Part 2. The hypothesis.

Posted: November 30, 2012 in Cancer, Cell Signaling, evolution, ketogenic diet, low-carbohydrate dietTags: biochemistry, Cancer, carbohydrate, evolution, hunter-gatherer, insulin

Guest post: Dr. Eugene J. Fine

Last time I discussed our pilot study showing the effects of carbohydrate (CHO) restriction & insulin inhibition (INSINH) in patients with advanced cancers. We described how the molecular effects of INSINH plus systemic (total body) effects like ketosis might inhibit cancer growth. My goal now is to present the underlying hypothesis behind the idea with the goal of understanding how patients with cancers might respond if we inhibited insulin’s actions? Should all patients respond? If not, why not? Might some patients get worse? These ideas were described briefly in our publication describing our pilot protocol. Read the rest of this entry »

Targeting insulin inhibition as a metabolic therapy in advanced cancer

Posted: October 15, 2012 in Cancer, Cell Signaling, ketogenic diet, low-carbohydrate dietTags: Cancer, carbohydrate, dietary guidelines, ketogenic diet, low carbohydrate

Dr. Eugene J. Fine. Dr. Feinman invited me to contribute a guest blog on our recently published cancer research study: “Targeting insulin inhibition as a metabolic therapy in advanced cancer: A pilot safety and feasibility dietary trial in 10 patients” which has now appeared in the October issue of the Elsevier journal Nutrition, with an accompanying editorial. Today’s post will focus on this dietary study, and its relation to the general problem of cancer and insulin inhibition. Part II, next week, will discuss in more detail, the hypothesis behind this study. Richard has already mentioned some of the important findings, but I will review them since the context of the study may shed additional light. Read the rest of this entry »

Suddenly last summer. Part II

Posted: October 2, 2012 in Cancer, Cell Signaling, low-carbohydrate dietTags: biochemistry, carbohydrate, cell biology, insulin, low carbohydrate, nutrition

In the last post, I had proclaimed a victory for dietary carbohydrate restriction or, more precisely, recognition of its explicit connection with cell signaling. I had anointed the BMC Washington meeting as the historic site for this grand synthesis. It may have been a matter of perception — many researchers in carbohydrate restriction entered the field precisely because it came from the basic biochemistry where the idea was that the key player was the hormone insulin and glucose was the major stimulus for pancreatic secretion of insulin. We had largely ignored the hook-up with cell-biology because of the emphasis on calorie restriction, and it may have only needed getting everybody in the same room to see that the role of insulin in cancer was not separate from its role in carbohydrate restriction. Read the rest of this entry »

Reading the Scientific Literature. A Guide to Flawed Studies.

Posted: July 11, 2012 in Association and Causality, The Nutrition Story, triglyceridesTags: low carbohydrate, nutrition, scientific literature, statistics

Doctor: Therein the patient

Must minister to himself.

Macbeth: Throw physic [medicine] to the dogs; I’ll none of it.

— William Shakespeare, Macbeth

The quality of nutrition papers even in the major scientific and medical journals is so variable and the lack of restraint in the popular media is so great that it is hard to see how the general public or even scientists can find out anything at all. Editors and reviewers are the traditional gate-keepers in science but in an area where rigid dogma has reached Galilean proportions, it is questionable that any meaningful judgement was made: it is easy to publish papers that conform to the party line (“Because of the deleterious effects of dietary fructose, we hypothesized that…”) and hard to publish others: when JAMA published George Bray’s “calorie-is-a-calorie” paper and I pointed out that the study more accurately supported the importance of carbohydrate as a controlling variable, the editor declined to publish my letter. In this, the blogs have performed a valuable service in providing an alternative POV but if the unreliability is a problem in the scientific literature, that problem is multiplied in internet sources. In the end, the consumer may feel that they are pretty much out there on their own. I will try to help. The following was posted on FatHead’s Facebook page:

How does one know if a study is ‘flawed’? I see a lot of posts on here that say a lot of major studies are flawed. How? Why? What’s the difference if I am gullible and believe all the flawed studies, or if I (am hopefully not a sucker) believe what the Fat Heads are saying and not to believe the flawed studies — eat bacon.

Where are the true studies that are NOT flawed…. and how do I differentiate? : /

My comment was that it was a great question and that it would be in the next post so I will try to give some of the principles that reviewers should adhere to. Here’s a couple of guides to get started. More in future posts:

1. “Healthy” (or “healthful”) is not a scientific term. If a study describes a diet as “healthy,” it is almost guaranteed to be a flawed study. If we knew which diets were “healthy,” we wouldn’t have an obesity epidemic. A good example is the paper by Appel, et al. (2005). “Effects of protein, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate intake on blood pressure and serum lipids: results of the OmniHeart randomized trial,” whose conclusion is:

“In the setting of a healthful diet, partial substitution of carbohydrate with either protein or monounsaturated fat can further lower blood pressure, improve lipid levels, and reduce estimated cardiovascular risk.”

It’s hard to know how healthful the original diet, a “carbohydrate-rich diet used in the DASH trials … currently advocated in several scientific reports” really is if removing carbohydrate improved everything.

Generally, understatement is good. One of the more famous is from Watson & Cricks’s 1953 paper in which they proposed the DNA double helix structure. They said “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.” A study with the word “healthy” is an infomercial.

2. Look for the pictures (figures). Presentation in graphic form usually means the author wants to explain things to you, rather than snow you. This is part of the Golden Rule of Statistics that I mentioned in my blogpost “The Seventh Egg” which discusses a very flawed study from Harvard on egg consumption. The rule comes from the book PDQ Statistics:

“The important point…is that the onus is on the author to convey to the reader an accurate impression of what the data look like, using graphs or standard measures, before beginning the statistical shenanigans. Any paper that doesn’t do this should be viewed from the outset with considerable suspicion.”

The Watson-Crick paper cited above had the diagram of the double-helix which essentially became the symbol of modern biology. It was drawn by Odile, Francis’s wife, who is described as being famous for her nudes, only one of which I could find on the internet.

Krauss, et. al. Separate effects of reduced carbohydrate intake and weight loss on atherogenic dyslipidemia.

The absence of a figure may indicate that the authors are not giving you a chance to actually see the results, that is, the experiment may not be flawed but the interpretation may be misleading, intentionally or otherwise. An important illustration of the principle is a paper published by Krauss. It is worth looking at this paper in detail because the experimental work is very good and the paper directly — or almost directly — confronts a big question in diet studies: when you reduce calories by cutting out carbohydrate, is the effect due simply to lowering calories or is there a specific effect of carbohydrate restriction. The problem is important since many studies compare low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets where calories are reduced on both. Because the low-carbohydrate diet generally has the better weight loss and better improvement in HDL and triglycerides, it is said that it was the weight loss that caused the lipid improvements.

So Krauss compared the effects of carbohydrate restriction and weight loss on the collection of lipid markers known collectively as atherogenic dyslipidemia. The markers of atherogenic dyslipidemia, which are assumed to predispose to cardiovascular disease, include high triglycerides (triacylglycerol), low HDL and high concentrations of the small dense LDL.

Here is how the experiment was set up: subjects first consumed a baseline diet of 54% of energy as carbohydrate, for 1 week. They were then assigned to one of four groups. Either they continued the baseline diet, or they kept calories constant but reduced carbohydrate by putting fat in its place. The three lower carbohydrate diets had 39 % or 26 % carbohydrate or 26 % carbohydrate with higher saturated fat. After 3 weeks on constant calories but reduced carbohydrate, calories were decreased by 1000 kcal/d for 5 week and, finally, energy was stabilized for 4 weeks and the features of atherogenic dyslidemia were measured at week 13. The protocol is shown in the figure from Krauss’s paper:

The Abstract of the paper describes the outcomes and the authors’ conclusions.

Results: The 26%-carbohydrate, low-saturated-fat diet reduced [atherogenic dylipidemia]. These changes were significantly different from those with the 54%-carbohydrate diet. After subsequent weight loss, the changes in all these variables were significantly greater…(my italics)

Now there is something odd about this. It is the last line of the conclusion that is really weird. If you lose weight, the effect of carbohydrate is not significant? As described below, Jeff Volek and I re-analyzed this paper so I have read that line a dozen times and I have no idea what it means. In fact, the whole abstract is strange. It will turn out that the lower (26 %) is certainly “significantly different from.. the 54%-carbohydrate diet” but it is not just different but much better. Why would you not say that? The Abstract is generally written so that it sounds negative about low carbohydrate effects but it is already known from Krauss’s previous work and others that carbohydrate restriction has a beneficial effect on lipids and the improvements in lipid markers occur on low-carbohydrate diets whether weight is lost or not. The last sentence doesn’t seem to make any sense at all. For one thing, the experiment wasn’t done that way. As set up, weight loss came after carbohydrate restriction. So, let’s look at the data in the paper. There are few figures in the paper and Table 2 in the paper presents the results in a totally mind-numbing layout. Confronted with data like this, I sometimes stop reading. After all, if the author doesn’t want to conform to the Golden Rule of Statistics, if they don’t want to really explain what they accomplished, how much impact is the paper going to have. In this case, however, it is clear that the experiment was designed correctly and it just seems impossible from previous work that this wouldn’t support the benefits of carbohydrate restriction and the negative tone of the Abstract needs to be explained. So we all had to slog through those tables. Let’s just look at the triglycerides since this is one of the more telling attributes of atherogenic dyslpidemia. Here’s the section from the Table:

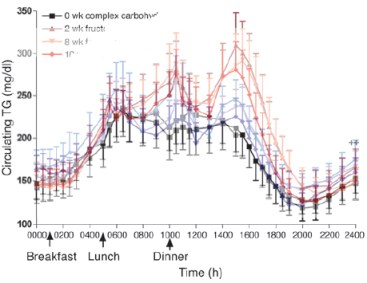

Well this looks odd in that the biggest change is in the lowest carb group with high SF but it’s hard to tell what the data look like. First it is reported as logarithms. You sometime take logs of your data in order to do a statistical determination but that doesn’t change the data and it is better to report the actual value. In any case, it’s easy enough to take antilogs and we can plot the data. This is what it looks like:

It’s not hard to see what the data really show: Reducing carbohydrate has an overwhelming effect on triglycerides even without weight loss. When weight loss is introduced, the high carbohydrate diets still can’t equal the performance of the carbohydrate reduction phase. (The dotted line in the figure are data from Volek’s earlier work which Krauss forgot to cite).

The statements in the Conclusion from the Abstract are false and totally misrepresent the data. It is not true as it says “carbohydrate restriction and weight loss provide equivalent…” effects. The carbohydrate-reduction phase is dramatically better than the calorie restriction phase and it is not true that they are “non-additive” Is this an oversight? Poor writing? Well, nobody knows what Krauss’s motivations were but Volek and I plotted all of the data from Krauss’s paper and we published a paper in Nutrition & Metabolism providing an interpretation of Krauss’s work (with pictures). Our conclusion:

Summary Although some effort is required to disentangle the data and interpretation, the recent publication from Krauss et al. should be recognized as a breakthrough. Their findings… make it clear that the salutary effects of CR on dyslipidemia do not require weight loss, a benefit that is not a feature of strategies based on fat reduction. As such, Krauss et al. provides one of the strongest arguments to date for CR as a fundamental approach to diet, especially for treating atherogenic dyslipidemia.

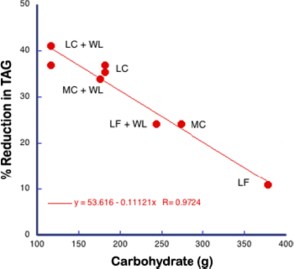

An important question in this experiment, however, is whether even in the calorie reduction phase, calories are actually the important variable. This is a general problem in calorie restriction studies if for no other reason than that there is no identified calorie receptor. When we published this data, Mike Eades pointed out that in the phase in which Krauss reduced calories, it was done by reducing macronutrients across the board so carbohydrate was also reduced and that might be the actual controlling variable so we plotted the TAG against carbohydrate in each phase (low, medium and high carb (LC, MC, HC) without or with weight loss (+WL) and the results are shown below

This is remarkably good agreement for a nutrition study. When you consider carbohydrates as the independent variable, you can see what’s going on. Or can you? After all, by changing the variables you have only made an association between carbohydrate and outcome of an experiment. So does this imply a causal relation between carbohydrate and triglycerides or not? It is widely said that observational studies do not imply causality, that observational studies can only provide hypothesis for future testing. It certainly seems like causality is implied here. It will turn out that a more accurate description is that observational studies do not necessarily imply causality and I will discuss that in the next posts. The bottom line will be that there is flaw in grand principles like “Random controlled trials are the gold standard.” “Observational studies are only good for generating hypotheses,” “Metabolic Ward Studies are the gold standard.” Science doesn’t run on such arbitrary rules.

Making Americans Afraid of Meat.

Posted: May 13, 2012 in Association and Causality, Crisis in Nutrition, Red Meat, saturated fatTags: carbohydrate, Meat Intake and Mortality, red meat,, statistics

TIME: You’re partnering with, among others, Harvard University on this. In an alternate Lady Gaga universe, would you have liked to have gone to Harvard?

Lady Gaga: I don’t know. I am going to Harvard today. So that’ll do.

— Belinda Luscombe, Time Magazine, March 12, 2012

There was a sense of déja-vu about the latest red meat scare and I thought that my previous post as well as those of others had covered the bases but I just came across a remarkable article from the Harvard Health Blog. It was entitled “Study urges moderation in red meat intake.” It describes how the “study linking red meat and mortality lit up the media…. Headline writers had a field day, with entries like ‘Red meat death study,’ ‘Will red meat kill you?’ and ‘Singing the blues about red meat.”’

What’s odd is that this is all described from a distance as if the study by Pan, et al (and likely the content of the blog) hadn’t come from Harvard itself but was rather a natural phenomenon, similar to the way every seminar on obesity begins with a slide of the state-by-state development of obesity as if it were some kind of meteorologic event.

When the article refers to “headline writers,” we are probably supposed to imagine sleazy tabloid publishers like the ones who are always pushing the limits of first amendment rights in the old Law & Order episodes. The Newsletter article, however, is not any less exaggerated itself. (My friends in English Departments tell me that self-reference is some kind of hallmark of real art). And it is not true that the Harvard study was urging moderation. In fact, it is admitted that the original paper “sounded ominous. Every extra daily serving of unprocessed red meat (steak, hamburger, pork, etc.) increased the risk of dying prematurely by 13%. Processed red meat (hot dogs, sausage, bacon, and the like) upped the risk by 20%.” That is what the paper urged. Not moderation. Prohibition. Who wants to buck odds like that? Who wants to die prematurely?

It wasn’t just the media. Critics in the blogosphere were also working over-time deconstructing the study. Among the faults that were cited, a fault common to much of the medical literature and the popular press, was the reporting of relative risk.

The limitations of reporting relative risk or odds ratio are widely discussed in popular and technical statistical books and I ran through the analysis in the earlier post. Relative risk destroys information. It obscures what the risks were to begin with. I usually point out that you can double your odds of winning the lottery if you buy two tickets instead of one. So why do people keep doing it? One reason, of course, is that it makes your work look more significant. But, if you don’t report the absolute change in risk, you may be scaring people about risks that aren’t real. The nutritional establishment is not good at facing their critics but on this one, they admit that they don’t wish to contest the issue.

Nolo Contendere.

“To err is human, said the duck as it got off the chicken’s back”

— Curt Jürgens in The Devil’s General

Having turned the media loose to scare the American public, Harvard now admits that the bloggers are correct. The Health NewsBlog allocutes to having reported “relative risks, comparing death rates in the group eating the least meat with those eating the most. The absolute risks… sometimes help tell the story a bit more clearly. These numbers are somewhat less scary.” Why does Dr. Pan not want to tell the story as clearly as possible? Isn’t that what you’re supposed to do in science? Why would you want to make it scary?

The figure from the Health News Blog:

|

Deaths per 1,000 people per year |

||

| 1 serving unprocessed meat a week | 2 servings unprocessed meat a day | |

| Women |

7.0 |

8.5 |

| 3 servings unprocessed meat a week | 2 servings unprocessed meat a day | |

| Men |

12.3 |

13.0 |

Unfortunately, the Health Blog doesn’t actually calculate the absolute risk for you. You would think that they would want to make up for Dr. Pan scaring you. Let’s calculate the absolute risk. It’s not hard.Risk is usually taken as probability, that is, number cases divided by total number of participants. Looking at the men, the risk of death with 3 servings per week is equal to the 12.3 cases per 1000 people = 12.3/1000 = 0.1.23 = 1.23 %. Now going to 14 servings a week (the units in the two columns of the table are different) is 13/1000 = 1.3 % so, for men, the absolute difference in risk is 1.3-1.23 = 0.07, less than 0.1 %. Definitely less scary. In fact, not scary at all. Put another way, you would have to drastically change the eating habits (from 14 to 3 servings) of 1, 429 men to save one life. Well, it’s something. Right? After all for millions of people, it could add up. Or could it? We have to step back and ask what is predictable about 1 % risk. Doesn’t it mean that if a couple of guys got hit by cars in one or another of the groups whether that might not throw the whole thing off? in other words, it means nothing.

Observational Studies Test Hypotheses but the Hypotheses Must be Testable.

It is commonly said that observational studies only generate hypotheses and that association does not imply causation. Whatever the philosophical idea behind these statements, it is not exactly what is done in science. There are an infinite number of observations you can make. When you compare two phenomena, you usually have an idea in mind (however much it is unstated). As Einstein put it “your theory determines the measurement you make.” Pan, et al. were testing the hypothesis that red meat increases mortality. If they had done the right analysis, they would have admitted that the test had failed and the hypothesis was not true. The association was very weak and the underlying mechanism was, in fact, not borne out. In some sense, in science, there is only association. God does not whisper in our ear that the electron is charged. We make an association between an electron source and the response of a detector. Association does not necessarily imply causality, however; the association has to be strong and the underlying mechanism that made us make the association in the first place, must make sense.

What is the mechanism that would make you think that red meat increased mortality. One of the most remarkable statements in the original paper:

“Regarding CVD mortality, we previously reported that red meat intake was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease2, 14 and saturated fat and cholesterol from red meat may partially explain this association. The association between red meat and CVD mortality was moderately attenuated after further adjustment for saturated fat and cholesterol, suggesting a mediating role for these nutrients.” (my italics)

This bizarre statement — that saturated fat played a role in increased risk because it reduced risk— was morphed in the Harvard News Letters plea bargain to “The authors of the Archives paper suggest that the increased risk from red meat may come from the saturated fat, cholesterol, and iron it delivers;” the blogger forgot to add “…although the data show the opposite.” Reference (2) cited above had the conclusion that “Consumption of processed meats, but not red meats, is associated with higher incidence of CHD and diabetes mellitus.” In essence, the hypothesis is not falsifiable — any association at all will be accepted as proof. The conclusion may be accepted if you do not look at the data.

The Data

In fact, the data are not available. The individual points for each people’s red meat intake are grouped together in quintiles ( broken up into five groups) so that it is not clear what the individual variation is and therefore what your real expectation of actually living longer with less meat is. Quintiles are some kind of anachronism presumably from a period when computers were expensive and it was hard to print out all the data (or, sometimes, a representative sample). If the data were really shown, it would be possible to recognize that it had a shotgun quality, that the results were all over the place and that whatever the statistical correlation, it is unlikely to be meaningful in any real world sense. But you can’t even see the quintiles, at least not the raw data. The outcome is corrected for all kinds of things, smoking, age, etc. This might actually be a conservative approach — the raw data might show more risk — but only the computer knows for sure.

Confounders

“…mathematically, though, there is no distinction between confounding and explanatory variables.”

— Walter Willett, Nutritional Epidemiology, 2o edition.

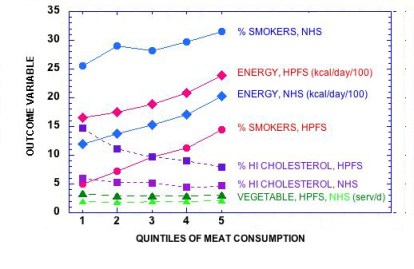

You make a lot of assumptions when you carry out a “multivariate adjustment for major lifestyle and dietary risk factors.” Right off , you assume that the parameter that you want to look at — in this case, red meat — is the one that everybody wants to look at, and that other factors can be subtracted out. However, the process of adjustment is symmetrical: a study of the risk of red meat corrected for smoking might alternatively be described as a study of the risk from smoking corrected for the effect of red meat. Given that smoking is an established risk factor, it is unlikely that the odds ratio for meat is even in the same ballpark as what would be found for smoking. The figure below shows how risk factors follow the quintiles of meat consumption. If the quintiles had been derived from the factors themselves we would have expected even better association with mortality.

The key assumption is that the there are many independent risk factors which contribute in a linear way but, in fact, if they interact, the assumption is not appropriate. You can correct for “current smoker,” but biologically speaking, you cannot correct for the effect of smoking on an increased response to otherwise harmless elements in meat, if there actually were any. And, as pointed out before, red meat on a sandwich may be different from red meat on a bed of cauliflower puree.

This is the essence of it. The underlying philosophy of this type of analysis is “you are what you eat.” The major challenge to this idea is that carbohydrates, in particular, control the response to other nutrients but, in the face of the plea of nolo contendere, it is all moot.

Who paid for this and what should be done.

We paid for it. Pan, et al was funded in part by 6 NIH grants. (No wonder there is no money for studies of carbohydrate restriction). It is hard to believe with all the flaws pointed out here and, in the end, admitted by the Harvard Health Blog and others, that this was subject to any meaningful peer review. A plea of no contest does not imply negligence or intent to do harm but something is wrong. The clear attempt to influence the dietary habits of the population is not justified by an absolute risk reduction of less than one-tenth of one per cent, especially given that others have made the case that some part of the population, particularly the elderly may not get adequate protein. The need for an oversight committee of impartial scientists is the most important conclusion of Pan, et al. I will suggest it to the NIH.

Guest Review: Nutritional Chromodynamics

Posted: April 1, 2012 in Guest BlogTags: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, red meat,

April 1, 2012. Piltdown, East Sussex, UK . Two prominent researchers, Drs. Ferdinand I. Charm and June E. Feigen of the University of Piltdown Center for Applied Nutrition (PCAN), submit the following guest review on a ground-breaking area of nutrition.

Nutrition is frequently accused of being a loose kind of science, not defining its terms and speaking imprecisely. Complex carbohydrates, for example, still refer, in organic chemistry, to polysaccharides such as starches and for many years, it was absolute dogma in nutrition that complex carbohydrates were more slowly absorbed than simple sugars. Science advances, however, and when measurements were actually made it was found not to be so simple, giving rise to the concept of the glycemic index. The term “complex,” had since then been used loosely but has currently evolved to have a more precise meaning derived from mathematics, that is, as in complex numbers, having a real part and an imaginary part although the recent Guidelines from the USDA make it difficult to tell which is which. In any case, the glycemic index has expanded to the concept of a glycemic load and now there is even more hope on the horizon.

Nutrition has borrowed a page from particle physics in the application of quantum chromodynamics. In the way of background, the discovery of the large number of subatomic particles and the need to classify them meant that designations had to go beyond charge and spin to include strangeness and the three flavors of quarks. Ultimately, it was decided that quarks have an additional degree of freedom, called color and the strong interaction was identified as a color force. A large amount of evidence supports this idea with interaction via the gluons.

Nutritional Chromodynamics.

A similar idea has arisen in nutrition and it is now clear that the more color, the better and extensive experimental work at CARN is currently under way (Figure 1). The recent CRAYOLA study showed the value of spectral nutrient density. Support for the theory was summarized in a recent press release:

Blueberries were up there, the wild type being the best.

“The wild blueberries are blue inside as well as blue outside. The ones we normally eat are sort of white inside. So there are more of the antioxidants in these all-blue blueberries.”

Along the line of color is good, cranberries were close behind as were blackberries.

But what about vegetables?

Dried red beans topped the list overall–red kidney and pinto beans were also in the top 10. But surprisingly, so are artichokes. “This is sort of interesting because they are not deeply colored, the inside, the part that we actually consume is white or very pale green but never the less they contain very large amounts of antioxidants.”

There are nuts that did not make it into the top twenty but did have high enough content worthy of mention– pecans, hazelnuts and walnuts were the ones with the greatest antioxidant content. But the antioxidants are concentrated, so you need only a handful a day to get the amount you need.

The problem here may be the bland coloration of the nuts. This has been jarring to some theorists, leading many to question whether the Standard Model of nutrition will last, or whether the highly abstract bean-string theory will ultimately prevail. The recent identification of chocolate with the dark matter that fills the majority of the universe, however, has established the field of nutritional chromodynamics. Still, critics point to the problem of red meat, one of the very few foods that actually decreased during the epidemic of obesity. By applying the USDA Nutritional Guidelines, however, this result can be made to vanish.

Figure 1 Souper-Collider at CARN (Centre Alimentaire de Recherche Nucléaire).

Although this is pretty convincing, there is the uncertainty principle. Because the outcome of a nutritional experiment and its support for the experimenter’s theory rarely commute, it is impossible to simultaneously measure outcome and whether the results mean anything. Again borrowing from particle physics, there is the concept of the virtual particle that mediates interaction between other particles. The evolving principle in the field of nutritional chromodynamics is the existence of the mayon, the virtual particle that mediates the so-called Dietary Weak Interaction or DWI, as in “phytochemicals may prevent cancer.”

And then there is the matter of Quark. Most physicists know that Quark is the German word for sour cream and many physicists on tour in Germany have their picture taken in front of delicatessens selling Quark (at least those who don’t have their picture taken in front of a jewelry store). Less widely known outside of the German-speaking countries is that Quark colloquially means nonsense or trash. In any case, it’s pretty clear at this point that, the Tevatron results notwithstanding, blueberries and sour cream are the real Top Quark.