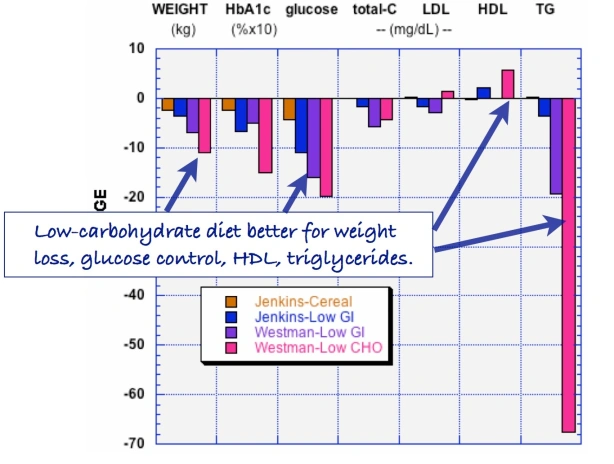

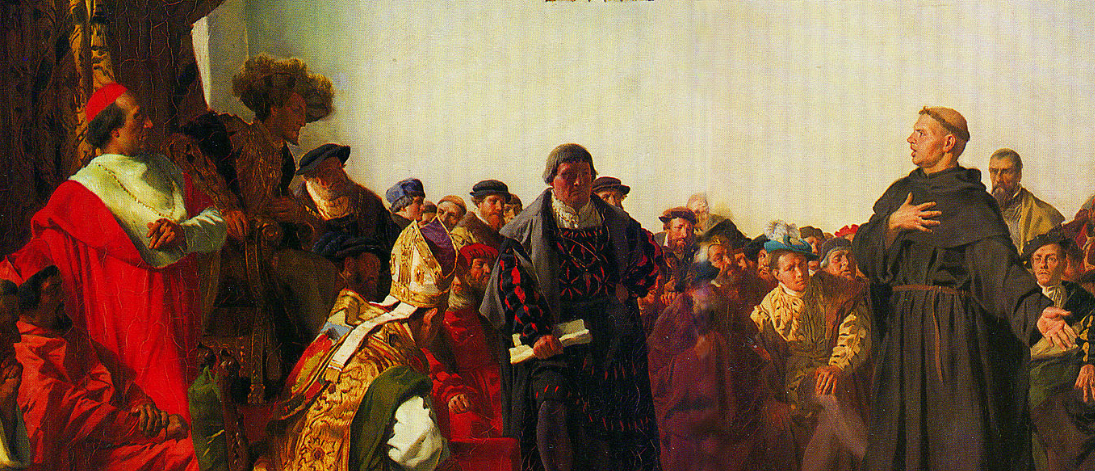

Our 2015 paper, Low-carbohydrate diets as the first approach in the treatment of diabetes. Review and evidence-base, summarized the clinical experience and the research results of the 26 authors. Meant to be a kind of manifesto on theory and practice, the first version of the manuscript was submitted to a couple of major journals under the title “The 15 Theses on…” harking back to Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. A critique of Church practices, particularly indulgences — for a few bucks, we get you or your loved ones out of purgatory — the Theses were supposed to have been nailed by Luther to the door of a church in Wittenberg. Our MS was rejected by BMJ and New England Journal although, like the original 95, it did not seem particularly radical — The American Diabetes Association (ADA) acknowledges that dietary carbohydrate is the major source of high blood glucose and most of our points of evidence were based on pretty solid fact. Anyway, somebody suggested that we were, in effect, trying to nail our low-carbohydrate paper to the door of the ADA and, in the end, we changed the name to “evidence base” and it was ultimately published.

Until recently, I had not noticed the extensive parallels of the current low-carbohydrate revolution with the Protestant Reformation. The recent imperious and rather savage actions of professional organizations, notably two in Australia, the DAA (Dietitian’s Association of Australia) and AHPRA (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency) in clamping down on their own members for deviation from orthodoxy brought out the similarities. Unlike Luther, who felt that the church really needed his help in getting abuses straightened out, Jennifer Elliott, a dietitian with an established practice of 30 years and Gary Fettke an orthopedic surgeon, thought that they were just doing their job and that, however, non-standard, the low-carbohydrate diets that they recommended for people with diabetes, was far from heresy. Because of the ties between government health agencies, Jennifer ultimately lost her job and Gary is under the bizarre order not to recommend diets to his patients because, as an orthopedic surgeon, there is “nothing associated with your medical training or education that makes you an expert or authority in the field of nutrition, diabetes or cancer.” (Those of us who are actively trying to upgrade the medical curriculum would question which part of the medical profession has such expertise or authority). Dr. Fettke’s training does, however, allow him to perform amputations which have diabetes as its greatest cause, second only to accidents. In any case, offering low-carbohydrate diets to patients has long been perceived as a threat by establishment medicine. While their claims that they, and they alone, can control the epidemics of obesity and diabetes has been at the level of offering reduction of time in purgatory. The medical establishment has been intolerant of criticism but has largely responded by delaying or preventing publication and by refusing to fund research that might get the “wrong” answer. The direct attacks on practitioners is new. There are several instances but the Australian cases distinctly represent desperation.

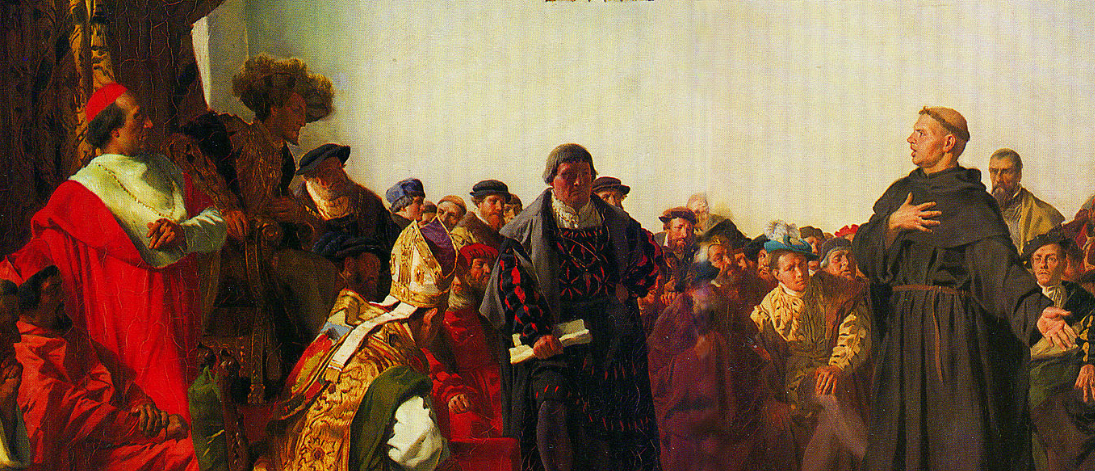

Luther at the Diet of Worms.

History of religion remains one of the gaps in my undergraduate liberal education and I was unfamiliar with the dramatic events surrounding Luther’s mission. The sixteenth century was a brutish time and I should have guessed how violent and oppressive would have been the response of the Catholic Church to Luther’s suggestions for improvement. After all, if you insisted on the word of the Bible rather than the word of priests, indeed, if you wanted direct access to a Bible in your own language rather than in Latin, then everybody could be their own savior. Being burnt at the stake was standard punishment for such heresy. We all know about Galileo’s brutal treatment and his being forced to recant his heliocentric theories, although at some point, he supposedly muttered, under his breath, “eppur se muove.” (It (the earth) does move anyway). That was almost a century after Luther’s protest and the danger was even greater in 1521. Luther, however, was a madman and refused to recant. Ultimately, he faced a trial at the Diet of Worms. (Contrary to popular opinion, “Diet” is an English word and means assembly; the German is Reichstag; Worms is in Germany, about 60 kilometres from Frankfurt-am-Main, and is pronounced “Vorms,” to rhyme with “norms,” but the joke is widely made, even by Shakespeare: see end of this post). At The Diet, Luther got off because a unanimous vote was required for conviction. He had an inside man, Frederick the Wise, the elector (as local political leaders were known) in his province. Frederick seems to have thought that Luther was good for tourism (and probably helped get the Church off his own back). Of course,“not guilty,” doesn’t mean innocent and, as for sex-offenders in our day, you could get killed in the street anyway and the authorities would understand. To protect him, Frederick had Luther “kidnapped,” disguised as an aristocrat with the alias Junker Jörg and he went to the mattresses in a Castle in Wartburg for a year until it all blew over. Lucas Cranach the Elder painted a portrait of Jörg, possibly to let followers know that Luther was still alive.

Junker Jörg aka Martin Luther.

Junker Jörg aka Martin Luther.

Heresy down under

So what had the Australian health professionals done to arouse the wrath of the “Church”? Not much. Jennifer Elliott has more than 30 years of experience and is the author of the excellent book, Baby Boomers, Bellies & Blood Sugars which is distinguished by its straight-forward practical approach and does not seem to tweak anybody’s beard. In fact, she was not really accused of any specific thing although the message was clear: low-carbohydrate high fat (LCHF) diets are forbidden. Trying to help out, I sent an email message to Claire Hewat, head of DAA. I attached the twelve-points of evidence paper and I explained our position. I pointed out that “Ms. Elliott seems quite upset and genuinely puzzled since carbohydrate restriction has been a treatment for diabetes more or less forever, certainly going back to Elliott Joslin (early twentieth century physician and authority on diabetes).”

Claire Hewat, head of DAA.

Claire Hewat, head of DAA.

I mentioned an interview with a reporter from the New York Times who could not understand the resistance to an established, successful and ultimately obvious therapy — you don’t give carbohydrates to people with a disease of carbohydrate intolerance — and I made the case that the burden of proof should be on anyone who didn’t approve. I suggested a discussion, “perhaps an online webinar, in which all sides present their case. I and/or my colleagues would be glad to participate.” Claire’s answer was that I was “obviously not in possession of all the facts in this matter, nor can I apprise you of them as this is part of a confidential complaints process …nor is DAA afraid of debate but this is not the place for it.”

Not to digress too much, I loved the idea that I did not have the facts right but the facts were not available because they were confidential. It reminded me of watching a scene in one of the old Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes movies. Holmes is playing the violin and his arch-enemy, Professor Moriarity suddenly appears in the doorway:

Moriarity: “Holmes, I’ve come to….Well, I am sure that you can deduce why I’ve come.”

Holmes: “Yes. And I’m sure you can deduce my answer.”

Moriarity: “So that’s final?”

Holmes: “I’m afraid so.”

Most distressing remains the fact that DAA constitutes a professional dietitians’ organization which should, as in Macbeth, “against his murderer shut the door, / Not bear the knife myself.” (Is this a DAAger I see before me?)

The details of Jennifer’s case are buried in evasive legal double-talk but the precipitating events make it clear that censure derives from her recommending low-carbohydrate diets to her patients with diabetes. Claire Hewat’s defense against this obvious lack of due process was that Jennifer was invited to appear before an inquiry, set up somewhat along the lines of the Diet of Worms, but Jennifer refused to appear. In fact, it would have been worse than the Diet in that there were no formal charges and even Luther had been afforded legal representation. There would certainly be no defenders, as Luther had in Frederick, the Wise. Most important, recanting was not an option — if it wasn’t about anything real, there was nothing to recant. (Like Luther, she probably would not have felt able to recant anyway). Jennifer declined to attend telling Claire that it appeared to be “an invitation to a beheading.” The net effect is that she lost her job and and legal recourse would likely be exorbitant.

The words

In the reformation, heresy might have meant simply owning a Bible in your native language, or really owning any Bible at all. The Church held onto the Latin versions which you did not get to see directly. Somewhat like governmental nutritional guidelines in our tme, it was not in your native language, and required an “expert” priest to tell you what’s what. The first English translation was accomplished by John Wycliffe and during the English Reformation, several people were actually executed for owning a Wycliffe Bible. I found it somewhat analogous to the persistent hatred of Dr. Atkins so long after his death, that, at some point, the Church in England had Wycliffe’s body exhumed and burnt at the stake.

Ultimately, Luther succeeded because of Gutenberg and the invention of movable type. Now you did not have to make copies by hand. Now Luther could really get the word out. And he wrote the word. During his period of lying low in Wartburg, he translated the Bible into German. And he published it. It was a big hit although the German population recognized that they had been swindled — financially as well as theologically — and history records a Peasant’s Revolt which was put down with great brutality. We recognize in all this parallels to what is really going on in the establishment’s determination to repress LCHF diets. And everybody recognizes the analog of Gutenberg’s press.

Unser Gutenberg and the Fettke case

Our Gutenberg is, of course, the internet where technical and scientific writings, once the province of specialists, can now be viewed by many and where they can be discussed widely. Publishers of many journals try to maintain pay-walls in keeping with somebody’s observation that publishers’ function used to be to make new information available while now they work to make information unavailable. (Many simultaneously cash in on open access which charges the authors outrageous fees). Whether the availability of scientific facts is out-weighed by proliferation of alternative facts is open to question but, on balance, we have a view, not only of the science, but of the inner workings of the health agencies that might otherwise be visible to only a few. And that’s how we have extensive access to the Fettke case and an associated Diet convened by the Australian Senate.

As reported by Marika Sboros, Fettke “cannot tell patients not to eat sugar. Why not? Because the country’s medical regulatory body, Australian Health Practitioners Regulatory Authority (AHPRA), says so….It has been investigating Fettke for more than two years now. That was after the first anonymous complaint from a DAA dietitian in 2014. Earlier this year, AHPRA told Fettke to stop talking about nutrition until it had decided on a suitable sanction.” and — I’m not making this up — “informed Fettke that it was investigating him for ‘inappropriately reversing (a patient’s) type 2 diabetes…’”

Dr. Gary Fettke testified at an Australian Senate Inquiry on November 1. and just “by coincidence,” a few hours later, AHPRA’s 2 1/2 year investigation came to an end and Fettke was told that he would be constrained from giving nutritional advice. In the end, this did not sit well with the Senate which undertook further hearing interrogating Martin Fletcher, the CEO of APHRA.

“Haven’t you got better things to do?”

You can see Martin Fletcher trying to defend AHPRA’s actions. on Youtube. At 31:25, one of the Senators asked “…if a health practitionerr is advising a patient to go on a … sensible, medically-accepted diet program, why would you risk-assess that and have all guns blazing? Haven’t you got better things to do?”

One of life’s great disappointments is that when you finally corner the bad guys, they turn out to be pathetic like Saddam Hussein. They don’t break down on the stand as in the old Perry Mason episodes. It is sad but it is also hard to feel much sympathy.

Martin Fletcher, CEO of AHPRA trying to juggle the truth at the Senate hearing.

“Bread thou art…”

It was a trip to Rome, intended to deepen his faith, that ultimately contributed to Luther’s transformation. He saw corruption on a grand scale but what really freaked him out was that corruption and vice were coupled with a cynical disregard for religious practice. A priest going through the motions of giving the elements in the sacrament muttered to himself “Bread thou art, and bread thou shalt remain; wine thou art, and wine thou shalt remain.”

That becomes the most distressing feature of this analogy. The quotation above, “There is nothing associated with your medical training or education that makes you an expert or authority in the field of nutrition, diabetes or cancer,” comes from a letter to Dr. Fettke that continued “Even if, in the future, your views on the benefits of the LCHF lifestyle become the accepted best medical practice, this does not change the fundamental fact that you are not suitably trained or educated as a medical practitioner to be providing advice or recommendations on this topic as a medical practitioner.”

This statement that treating disease is less important than loyalty to political power stands as the greatest exposition of the need for Reformation in Medicine.

Appendix. Shakespeare on the Diet of Worms.

Hamlet has been charged by his father’s Ghost with avenging the father’s murder by Claudius, the current king. Hamlet has put on an “antic disposition” to hide his motives. At one point, mistaking him for the King, Hamlet kills Polonius, a pompous court official, who is hiding behind a wall-hanging. The king hears about it and is pissed and wants to know where the body is (Act 4,Scene 3):

CLAUDIUS: Where’s Polonius?

HAMLET: At supper.

CLAUDIUS: At supper where?

HAMLET: Not where he eats, but where he is eaten. A certain convocation of politic worms are e’en [now] at him. Your worm is your only emperor for diet. We fat all creatures else to fat us, and we fat ourselves for maggots. Your fat king and your lean beggar is but variable service—two dishes, but to one table. That’s the end.

CLAUDIUS: Alas, alas!

HAMLET: A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath fed of that worm.

CLAUDIUS: What dost thou mean by this?

HAMLET: Nothing but to show you how a king may go a progress through the guts of a beggar.

CLAUDIUS: Where is Polonius?

HAMLET: In heaven. Send hither to see. If your messenger find him not there, seek him i’ th’ other place yourself. But if indeed you find him not within this month, you shall nose him as you go up the stairs into the lobby.

CLAUDIUS (to attendants) Go seek him there.

(Exeunt some attendants)

HAMLET: He will stay till ye come.

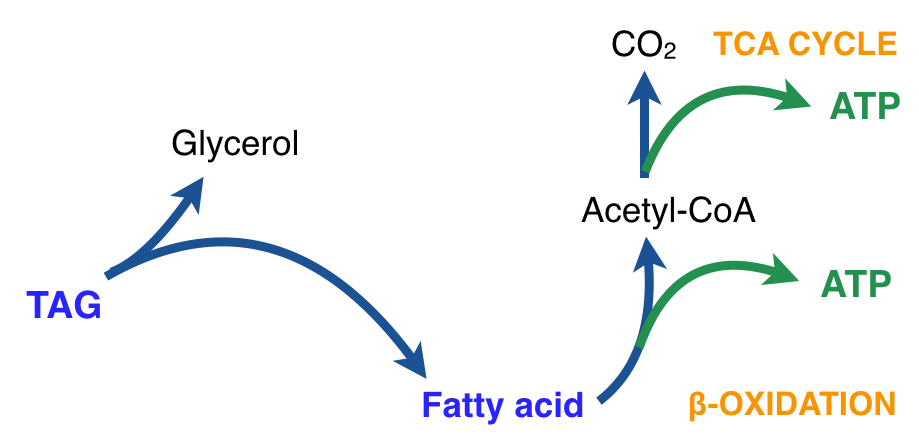

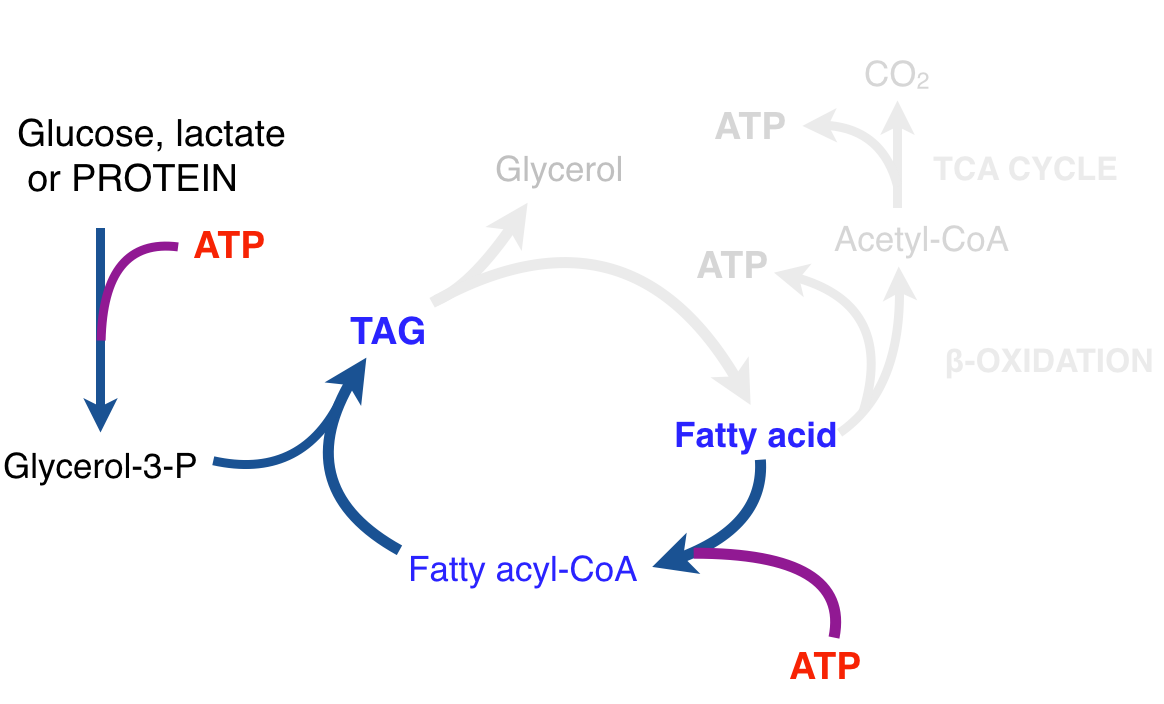

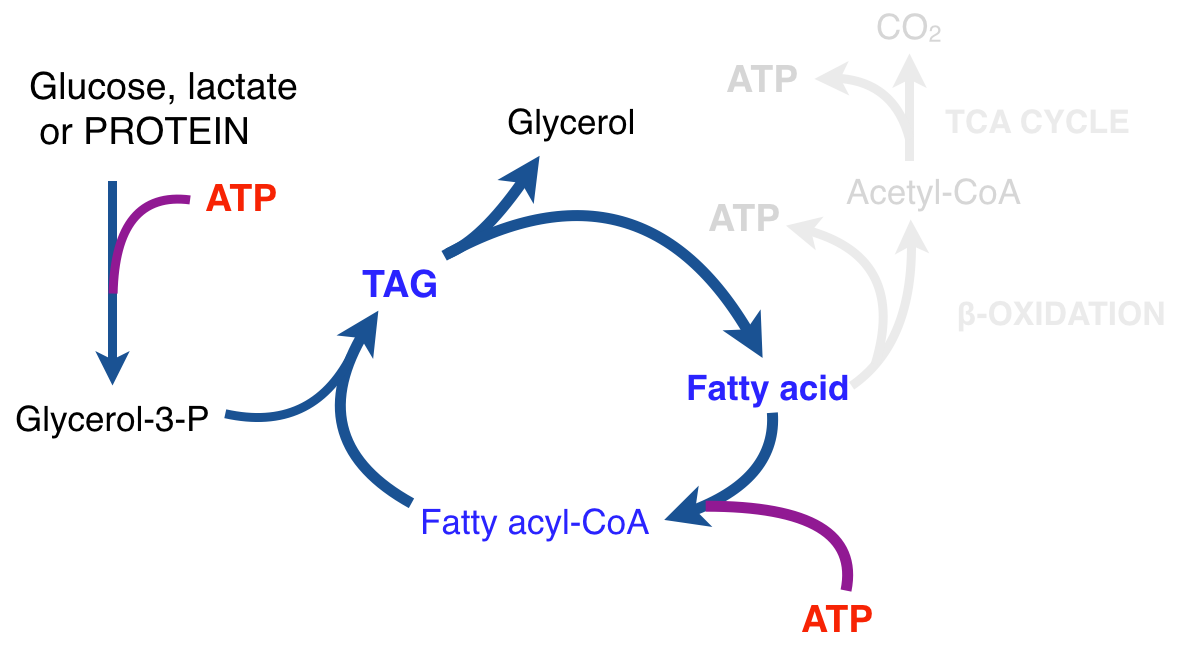

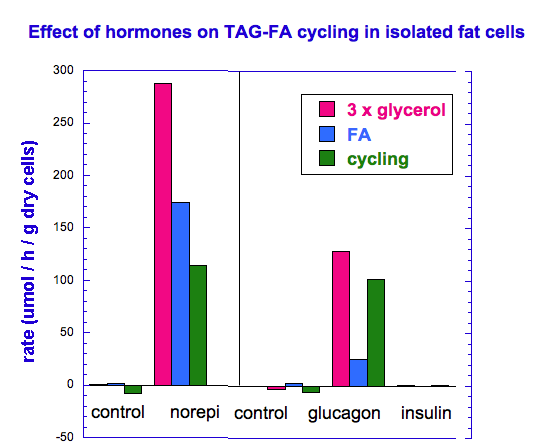

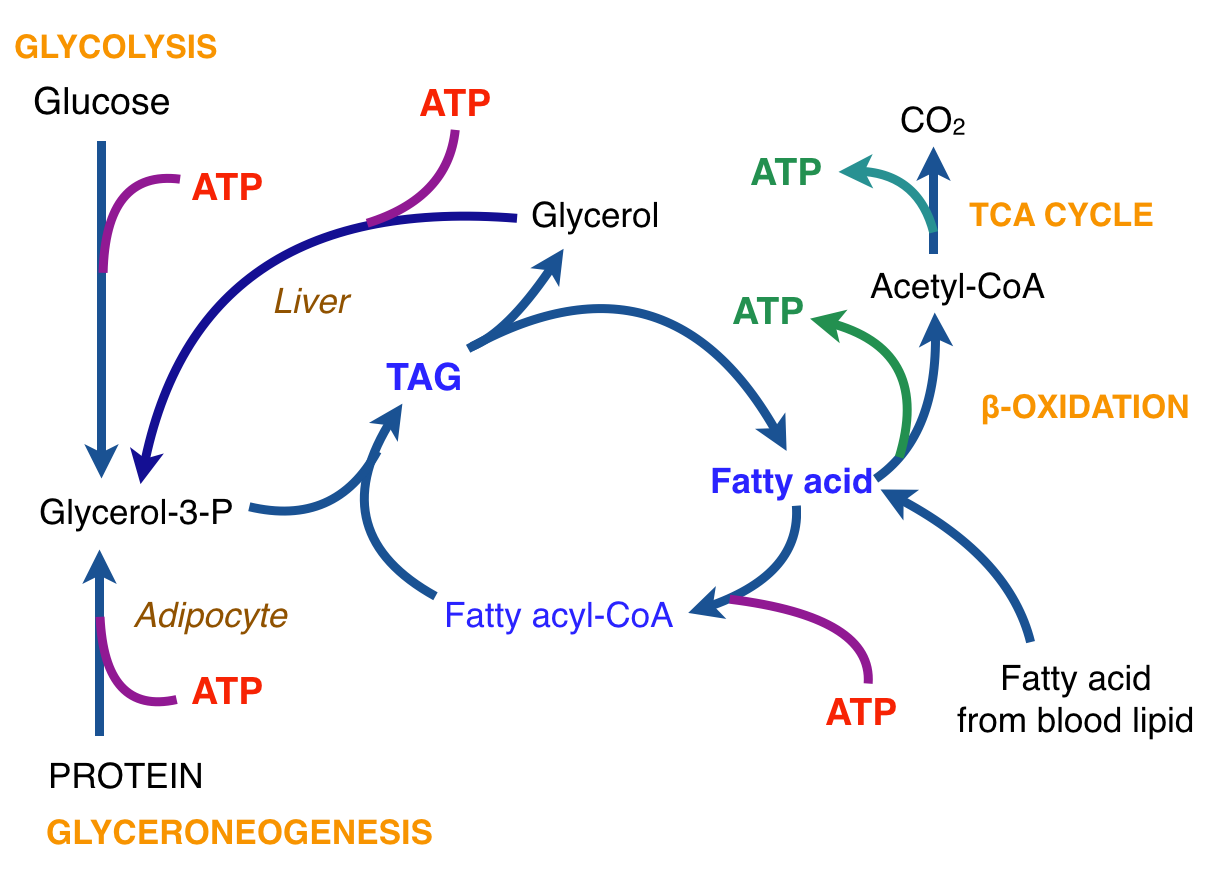

There is thus a steady-state that continuously readjusts levels of fat and fatty acid. The process will drift in the direction of oxidation when stored fat provides energy to other cells and will tend in the opposite direction — toward synthesis — when fat is stored. The important point is that the steady-state, like an equilibrium state, does not mean that everything has stopped. It means that the forward rate of breakdown is equal to the resynthesis rate. Every time there is a cycle, TAG → FA → TAG, however, energy is wasted — synthesis of TAG requires ATP, lipolysis is spontaneous and no ATP is re-syntesized. Why would such a thing evolve? The common name of the process is substrate cycle but because each cycle wastes ATP and accomplishes nothing — you get back the substrate that you started with — it has been referred to as a “futile cycle.” Why would the adipocyte waste energy in this way?

There is thus a steady-state that continuously readjusts levels of fat and fatty acid. The process will drift in the direction of oxidation when stored fat provides energy to other cells and will tend in the opposite direction — toward synthesis — when fat is stored. The important point is that the steady-state, like an equilibrium state, does not mean that everything has stopped. It means that the forward rate of breakdown is equal to the resynthesis rate. Every time there is a cycle, TAG → FA → TAG, however, energy is wasted — synthesis of TAG requires ATP, lipolysis is spontaneous and no ATP is re-syntesized. Why would such a thing evolve? The common name of the process is substrate cycle but because each cycle wastes ATP and accomplishes nothing — you get back the substrate that you started with — it has been referred to as a “futile cycle.” Why would the adipocyte waste energy in this way?

.

.

Junker Jörg aka Martin Luther.

Junker Jörg aka Martin Luther. Claire Hewat, head of DAA.

Claire Hewat, head of DAA.

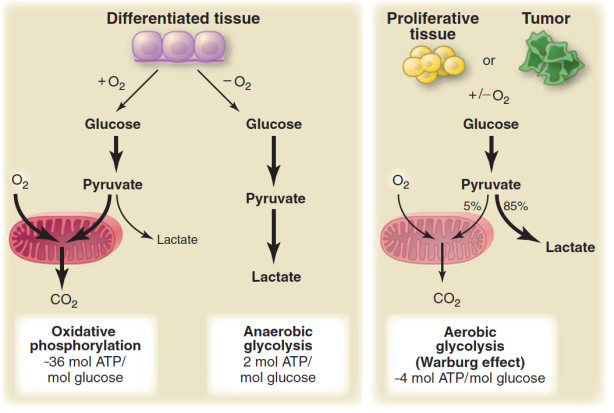

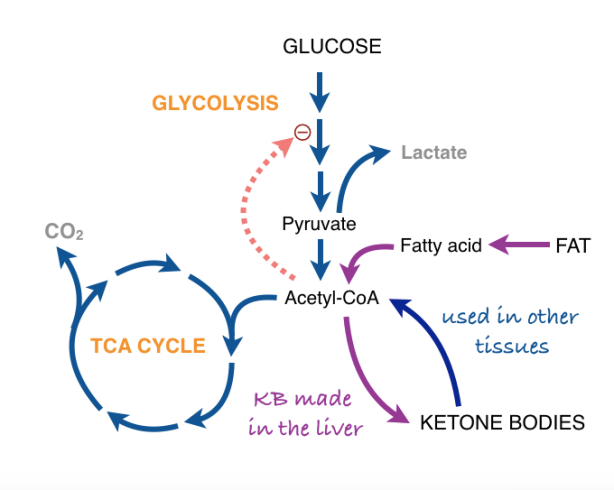

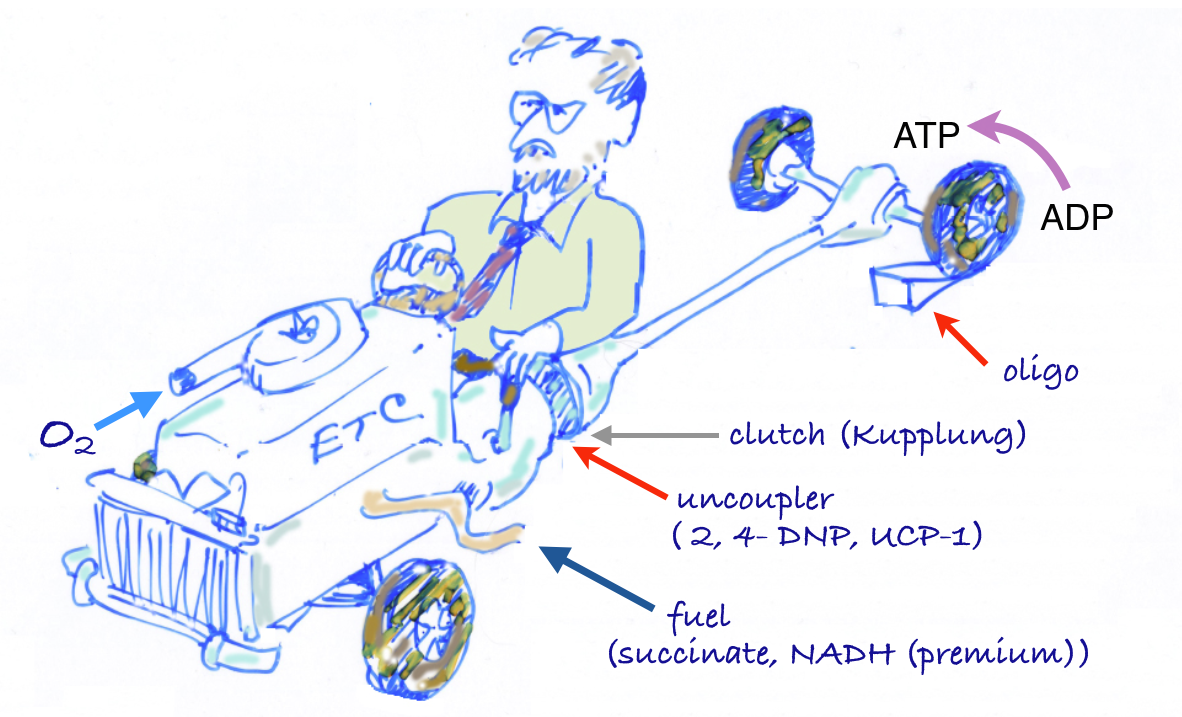

The car analogy of metabolic inhibitors. Figure from my lectures. Energy is generated in the TCA cycle and electron transport chain (ETC). The clutch plays the role of the membrane proton gradient, transmitting energy to the wheels which produce forward motion (phosphorylation of ADP). Uncouplers allow oxidation to continue — the TCA cycle is “racing” but to no effect. Other inhibitors (called oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors) include oligomycin which blocks the ATP synthase, analogous to a block under the wheels: no phosphorylation, no utilization of the gradient; no utilization, no gradient formation; no gradient, no oxidation. The engine “stalls.”

The car analogy of metabolic inhibitors. Figure from my lectures. Energy is generated in the TCA cycle and electron transport chain (ETC). The clutch plays the role of the membrane proton gradient, transmitting energy to the wheels which produce forward motion (phosphorylation of ADP). Uncouplers allow oxidation to continue — the TCA cycle is “racing” but to no effect. Other inhibitors (called oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors) include oligomycin which blocks the ATP synthase, analogous to a block under the wheels: no phosphorylation, no utilization of the gradient; no utilization, no gradient formation; no gradient, no oxidation. The engine “stalls.”