The attack was quite sudden although it appeared to have been planned for many years. The paper was published last week (Augustin LS, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ, Willett WC, Astrup A, Barclay AW, Bjorck I, Brand-Miller JC, Brighenti F, Buyken AE et al: Glycemic index, glycemic load and glycemic response: An International Scientific Consensus Summit from the International Carbohydrate Quality Consortium (ICQC). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2015, 25(9):795-815.

As indicated by the title, responsibility was taken by the self-proclaimed ICQC. It turned out to be a continuation of the long-standing attempt to use the glycemic index to co-opt the obvious benefits in control of the glucose-insulin axis while simultaneously attacking real low-carbohydrate diets. The authors participated in training in Stresa, Italy.

The operation was largely passive aggressive. While admitting the importance of dietary carbohydrate in controlling post-prandial glycemic, low-carbohydrate diets were ignored. Well, not exactly. The authors actually had a strong attack. The Abstract of the paper said (my emphasis):

“Background and aims: The positive and negative health effects of dietary carbohydrates are of interest to both researchers and consumers.”

Methods: International experts on carbohydrate research held a scientific summit in Stresa, Italy, in June 2013 to discuss controversies surrounding the utility of the glycemic index (GI), glycemic load (GL) and glycemic response (GR).”

So, for the record, the paper is about dietary carbohydrate and about controversies.

The Results in Augustin, et al were simply

“The outcome was a scientific consensus statement which recognized the importance of postprandial glycemia in overall health, and the GI as a valid and reproducible method of classifying carbohydrate foods for this purpose…. Diets of low GI and GL were considered particularly important in individuals with insulin resistance.”

A definition is always a reproducible way of classifying things, and the conclusion is not controversial: glycemia is important. Low-GI diets are a weak form of low-carbohydrate diet and they are frequently described as a politically correct form of carbohydrate restriction. It is at least a subset of carbohydrate restriction and one of the “controversies” cited in the Abstract is sensibly whether it is better or worse than total carbohydrate restriction. Astoundingly, this part of the controversy was ignored by the authors. Our recent review of carbohydrate restriction in diabetes had this comparison:

A question of research integrity.

It is considered normal scientific protocol that, in a scientific field, especially one that is controversial, that you consider and cite alternative or competing points of view. So how do the authors see low-carbohydrate diets fitting in? If you search the pdf of Augustin, et al on “low-carbohydrate” or “low carbohydrate,” there are only two in the text:

“Very low carbohydrate-high protein diets also have beneficial effects on weight control and some cardiovascular risk factors (not LDL-cholesterol) in the short term, but are associated with increased mortality in long term cohort studies [156],”

and

“The lowest level of postprandial glycemia is achieved using very low carbohydrate-high protein diets, but these cannot be recommended for long term use.”

There are no references for the second statement but very low carbohydrate diets can be and frequently are recommended for long term use and have good results. I am not aware of “increased mortality in long term cohort studies” as in the first statement. In fact, low-carbohydrate diets are frequently criticized for not being subjected to long-term studies. So it was important to check out the studie(s) in reference 156:

[156] Pagona L, Sven S, Marie L, Dimitrios T, Hans-Olov A, Elisabete W. Low carbohydrate-high protein diet and incidence of cardiovascular diseases in Swedish women: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;344.

Documenting increased mortality.

The paper is not about mortality but rather about cardiovascular disease and, oddly, the authors are listed by their first names. (Actual reference: Lagiou P, Sandin S, Lof M, Trichopoulos D, Adami HO, Weiderpass E: …. BMJ 2012, 344:e4026). This minor error probably reflects the close-knit “old boys” circle that functions on a first name basis although it may also indicate that the reference was not actually read so it was not discovered what the reference was really about.

Anyway, even though it is about cardiovascular disease, it is worth checking out. Who wants increased risk of anything. So what does Lagiou, et al say?

The Abstract of Lagiou says (my emphasis) “Main outcome measures: Association of incident cardiovascular diseases … with decreasing carbohydrate intake (in tenths), increasing protein intake (in tenths), and an additive combination of these variables (low carbohydrate-high protein score, from 2 to 20), adjusted for intake of energy, intake of saturated and unsaturated fat, and several non-dietary variables.”

Low-carbohydrate score? There were no low-carbohydrate diets. There were no diets at all. This was an analysis of “43, 396 Swedish women, aged 30-49 years at baseline, [who] completed an extensive dietary questionnaire and were followed-up for an average of 15.7 years.” The outcome variable, however, was only the “score” which the authors made up and which, as you might guess, was not seen and certainly not approved, by anybody with actual experience with low-carbohydrate diets. And, it turns out that “Among the women studied, carbohydrate intake at the low extreme of the distribution was higher and protein intake at the high extreme of the distribution was lower than the respective intakes prescribed by many weight control diets.” (In social media, this is called “face-palm”).

Whatever the method, though, I wanted to know how bad it was? The 12 years or so that I have been continuously on a low-carbohydrate diet might be considered pretty long term. What is my risk of CVD?

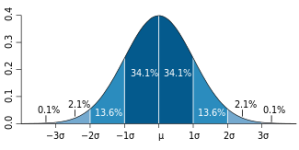

“Results: A one tenth decrease in carbohydrate intake or increase in protein intake or a 2 unit increase in the low carbohydrate-high protein score were all statistically significantly associated with increasing incidence of cardiovascular disease overall (n=1270)—incidence rate ratio estimates 1.04 (95% confidence interval 1.00 to 1.08), 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06), and 1.05 (1.02 to 1.08).”

Rate ratio 1.04? And that’s an estimate. That’s odds of 51:49. That’s what I am supposed to be worried about. But that’s the relative risk. What about the absolute risk? There were 43 396 women in the study with 1270 incidents, or 2.9 % incidence overall. So the absolute difference is about 1.48-1.42% = 0.06 % or less than 1/10 of 1 %.

Can such low numbers be meaningful? The usual answers is that if we scale them up to the whole population, we will save thousands of lives. Can we do that? Well, you can if the data are strong, that is, if we are really sure of the reliability of the independent variable. The relative risk in the Salk vaccine polio trial, for example, was in this ballpark but scaling up obviously paid off. In the Salk vaccine trial, however, we knew who got the vaccine and who didn’t. In distinction, food questionnaire’s have a bad reputation. Here is Lagiou’s description (you don’t really have to read this):

“We estimated the energy adjusted intakes of protein and carbohydrates for each woman, using the ‘residual method.’ This method allows evaluation of the “effect” of an energy generating nutrient, controlling for the energy generated by this nutrient, by using a simple regression of that nutrient on energy intake.…” and so on. I am not sure what it means but it certainly sounds like an estimate. So is the data itself any good? Well,

“After controlling for energy intake, however, distinguishing the effects of a specific energy generating nutrient is all but impossible, as a decrease in the intake of one is unavoidably linked to an increase in the intake of one or several of the others. Nevertheless, in this context, a low carbohydrate-high protein score allows the assessment of most low carbohydrate diets, which are generally high protein diets, because it integrates opposite changes of two nutrients with equivalent energy values.”

And “The long interval between exposure and outcome is a source of concern, because certain participants may change their dietary habits during the intervening period.”

Translation: we don’t really know what we did here.

In the end, Lagiou, et al admit “Our results do not answer questions concerning possible beneficial short term effects of low carbohydrate or high protein diets in the control of body weight or insulin resistance. Instead, they draw attention to the potential for considerable adverse effects on cardiovascular health of these diets….” Instead? I thought insulin resistance has an effect on CVD but if less than 1/10 of 1 % is “considerable adverse effects” what would something “almost zero” be.?

Coming back to the original paper by Augustin, et al, what about the comparison between low-GI diets and low-carbohydrate diets. The comparison in the figure above comes from Eric Westman’s lab. What do they have to say about that?

They missed this paper. Note: a comment I received suggested that I should have searched on “Eric” instead of “Westman.” Ha.

Overall, this is the evidence used by ICQC to tell you that low-carbohydrate diets would kill you. In the end, Augustin, et al is a hatchet-job, citing a meaningless paper at random. It is hard to understand why the journal took it. I will ask the editors to retract it.