The SBU (Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment) is charged by the Swedish government with assessing health care treatments. Their recent acceptance of low-carbohydrate diets as best for weight loss is one of the signs of big changes in nutrition policy. I am happy to reveal the next bombshell, this time from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) which will finally recognize the importance of reducing carbohydrate as the primary therapy in type 2 diabetes and as an adjunct in type 1. Long holding to a very reactionary policy — while there were many disclaimers, the ADA has previously held 45 – 60 % carbohydrate as some kind of standard — the agency has been making slow progress. A member of the writing committee who wishes to remain anonymous has given me a copy of the 2014 nutritional guidelines due to be released next year, an excerpt from which, I reproduce below. (more…)

Posts Tagged ‘dietary guidelines’

American Diabetes Association Embraces Low-Carbohydrate Diets. Can You Believe It?

Posted: December 27, 2013 in American Diabetes Association, diabetes, glucose, saturated fatTags: ADA, carbohydrate, diabetes, dietary guidelines, Gannon and Nuttall, low carbohydrate, nutrition

Health risks of low-carbohydrate diets.

Posted: September 26, 2013 in ACCORD, American Diabetes Association, diabetes, low-carbohydrate diet, statins, TZDTags: ACCORD, ADA, dietary guidelines, low carbohydrate, low-carbohydrate diets, statins, T2 diabetes, TZDs

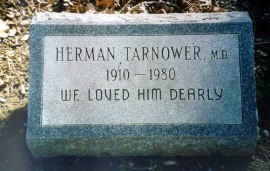

The only person definitely known to have died as a consequence of an association with a low-carbohydrate diet is Dr. Herman Tarnower, author of the Scarsdale diet, although, as they used to say on the old TV detective shows, the immediate cause of death was lead poisoning. His girlfriend shot him. Not that folks haven’t been looking for other victims. The Atkins diet is still the bête noire of physicians, at least those who aren’t on it — a study published a few years ago said that physicians were more likely to follow a low carbohydrate diet when trying to lose weight themselves, while recommending a low fat diets for their patients.

The only person definitely known to have died as a consequence of an association with a low-carbohydrate diet is Dr. Herman Tarnower, author of the Scarsdale diet, although, as they used to say on the old TV detective shows, the immediate cause of death was lead poisoning. His girlfriend shot him. Not that folks haven’t been looking for other victims. The Atkins diet is still the bête noire of physicians, at least those who aren’t on it — a study published a few years ago said that physicians were more likely to follow a low carbohydrate diet when trying to lose weight themselves, while recommending a low fat diets for their patients.

Targeting insulin inhibition as a metabolic therapy in advanced cancer

Posted: October 15, 2012 in Cancer, Cell Signaling, ketogenic diet, low-carbohydrate dietTags: Cancer, carbohydrate, dietary guidelines, ketogenic diet, low carbohydrate

Dr. Eugene J. Fine. Dr. Feinman invited me to contribute a guest blog on our recently published cancer research study: “Targeting insulin inhibition as a metabolic therapy in advanced cancer: A pilot safety and feasibility dietary trial in 10 patients” which has now appeared in the October issue of the Elsevier journal Nutrition, with an accompanying editorial. Today’s post will focus on this dietary study, and its relation to the general problem of cancer and insulin inhibition. Part II, next week, will discuss in more detail, the hypothesis behind this study. Richard has already mentioned some of the important findings, but I will review them since the context of the study may shed additional light. (more…)

The Patient’s Voice Project. Your Diabetes Story.

Posted: October 30, 2011 in American Diabetes Association, low-carbohydrate diet, The Nutrition StoryTags: ADA, carbohydrate, diabetes, dietary guidelines, low carbohydrate, low-fat

Doctor: Therein the patient must minister to himself.

Macbeth: Throw physic [medicine] to the dogs; I’ll none of it.

— William Shakespeare, Macbeth

The epidemic of diabetes, if it can be contained at all, will probably fall to the efforts of the collective voice of patients and individual dedicated physicians. The complete abdication of responsibility by the American Diabetes Association (sugar is okay if you “cover it with insulin”) and by other agencies and individual experts, and the media’s need to keep market share with each day’s meaningless new epidemiologic breakthrough leaves the problem of explanation of the disease and its treatment in the hands of individuals.

Jeff O’Connell’s recently published Sugar Nation provides the most compelling introduction to what diabetes really means to a patient, and the latest edition of Dr. Bernstein’s encyclopedic Diabetes Solution is the state-of-the art treatment from the patient-turned-physician. Although the nutritional establishment has been able to resist these individual efforts — the ADA wouldn’t even accept ads for Dr. Bernstein’s book in the early editions — practicing physicians are primarily interested in their patients and may not know or care what the expert nutritional panels say. You can send your diabetes story to Michael Turchiano (MTurchiano.PVP@gmail.com) and Jimmy Moore (livinlowcarbman@charter.net) at The Patient’s Voice Project.

The Patient’s Voice Project

The Patient’s Voice Project, which began soliciting input on Friday, is a research study whose results will be presented at the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) conference on Quest for Research Excellence, March 15-16 in Washington, D.C. The conference was originally scheduled for the end of August but there was a conflict with Hurricane Irene.

The Patients Voice Project is an outgrowth of the scheduled talk “Vox Populi,” the text for which is at the end of this post. A major stimulus was also our previous study on the Active Low-Carber Forums, an online support group. The March conference will present a session on “Crisis in Nutrition” that will include the results of the Patient’s Voice Project.

Official Notice from the Scientific Coordinator, Michael Turchiano

The Patient’s Voice Project is an effort to collect first hand accounts of the experience of people with diabetes (type 1 and type 2) with different diets. If you are a person with diabetes and would be willing to share your experiences with diet as a therapy for diabetes, please send information to Michael Turchiano (MTurchiano.PVP@gmail.com) and a copy to Jimmy Moore (livinlowcarbman@charter.net). Please include details of your diets and duration and whether you are willing to be cited by name in any publication.

It is important to point out that, whereas we think that the benefits of carbohydrate restriction have been greatly under-appreciated and under-recommended, the goal is to find out about people’s experiences:both benefits and limitations of different diets. If you have not had good success with low-carbohydrate diets, it is equally important to share these experiences.

- Indicate if you saw a physician or other health provider, what their attitudes were and whether you would be willing to share medical records.

- We are particularly interested in people who have switched diets and had different outcomes.

- Include any relevant laboratory or medical results that you think are relevant but we are primarily interested in your personal reactions to different diets and interaction with physicians and other health providers.

- Finally, please indicate what factors influenced your choices (physician or nutritionist recommendations, information on popular diets(?) or scientific publications).

Thanks for your help. The Patient’s Voice Project will analyze and publish conclusions in popular and scientific journals.

The Survey of the Active Low-Carber Forums

The Active Low-Carber Forums (ALCF) is an on-line support group that was started in 2000. At the time of our survey (2006), it had 86,000 members and currently has more than 130,000. Our original survey asked members of the forum to complete a 27-item questionnaire and to provide a narrative on any other health issues. Some of the narrative answers included in the published paper were as follows:

“I no longer have diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, joint pain, back pain and loss of energy.”

“I started low carbing for diabetes. My 3 month blood sugar was 8.9 when diagnosed. It is now 5.4. My doctor is thrilled with my diabetes control and as a side benefit, I lost all that weight!”

“I’m controlling my diabetes without meds or injecting insulin (with an a1c below 5), my lipid profile has improved, I’ve lost weight, I’ve gained both strength and endurance, and I’ve been able to discontinue one of my blood pressure meds.”

“I have much more energy, fewer colds or other health problems. I was able to go completely off oral diabetes medication.”

The survey covered a number of topics. We found that most respondents had the perception that they ate less food than before their low-carb diet, and most felt that the major change in their diet was a large increase in the consumption of green vegetables and a corresponding large decrease in fruit intake.

Physicians Attitudes in the ALCF survey

The Patient’s Voice Project is likely to tell us as much about physicians, or at least their interaction with patients, as about the patients themselves. We found in the ACLF survey that slightly more than half of the people who responded said that they had consulted a physician. We were surprised that about 55 % said that the physician or other health professional was supportive of their diet. Another 30 % or so fit the category of “did not have an opinion but was encouraging after seeing results.” Only 6 % of responders indicated that “they were discouraging even after I showed good results,” which may be a surprising result depending on your feeling about the rationality of doctors vs hostility to the Atkins diet. Perusal of patients’ opinions on diabetes websites, however, suggests that the story on people with diabetes will not be as encouraging.

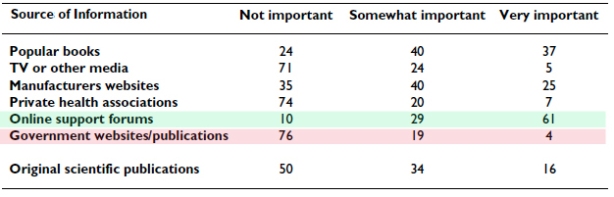

The Survey on Sources of Information

Given the contentious nature of the debate on diet in diabetes therapy, it is not surprising that a group following a low-carb strategy would not put much stock in official sources. The table below shows the breakdown on sources of information from the ALCF survey. Of the half of respondents who said that they relied on original scientific publications, 20 % felt they had generally inadequate access (important articles were not accessible) whereas 61 % felt that access was adequate and were able to see most articles that they wanted.

Voices of Dissatisfaction.

Posts on the ALCLF itself reinforced the idea that official recommendations were not only a limited source of information but that many were perceived as misleading. Typical posts cited in the paper:

“The ‘health experts’ are telling kids and parents the wrong foods to eat. Until we start beating the ‘health experts’ the kids won’t get any better. If health care costs are soaring and type 2 diabetes and its complications, as are most of these expenses why are we not putting a ‘sin’ tax on high glycemic foods to cut consumption and help pay for these cost? Beat the ‘health experts’ – not the kids!”

While I am not a fan of sin taxes, the dissatisfaction is clear, and…

“Until I researched it three years ago – I thought the most important thing was low fat. So I was eating the hell out of low fat products and my health continued to get worse.”

Similarly, the recent article in Diabetes Health by Hope Warshaw http://bit.ly/mYm2O3 with its bizarre recommendation for people with diabetes to increase their carbohydrate intake elicited a number of statements of dissatisfaction:

“Respectfully, this column is not helpful to diabetics and probably dangerous. I am going on 6 years of eating 30-35 carbs/day. My A1c has been in the “non-diabetic” range ever since I went this route and I feel better than I have in years. I am not an exception among the many folks I know who live a good life on restricted carb diets.”

“…carbohydrates are a very dangerous and should be consumed with caution and knowledge. i had awful lipids and blood sugar control on a low fat/high carb diet. now that i have switched to a lower carb diet – all my numbers are superb. and the diet is easy to follow and very satisfying!”

Summary:

The Project is intended to bring out the patient’s perspective on diet as therapy in diabetes. The goals are to document people’s experience in finding the right diet. In particular, we are interested in whether switching to a low-carbohydrate diet provided improvement over the recommended diet typical of the ADA. Or not. We are looking for a narrative that can bring out how people make decisions on choosing a diet and sticking with it: the influences of physicians, the media and personal experimentation. Your diabetes story.

Text of Abstract for the Original ORI Conference

Crisis in Nutrition: IV. Vox Populi

Authors: Tom Naughton, Jimmy Moore, Laura Dolson

Objective: Blogs and other social media provide insights into how a growing share of the population views the current state of nutrition science and the official dietary recommendations. We ask what can be learned from online discussions among people who dispute and distrust the official recommendations.

Main points: A growing share of the population no longer trusts the dietary advice offered by private and government health agencies. They believe the supposed benefits of the low-fat, grain-based diets promoted by those agencies are not based on solid science and that benefits of low-carbohydrate diets have been deliberately squelched. The following is typical of comments the authors (whose websites draw a combined 1.5 million visitors monthly) receive daily:

“The medical and pharmaceutical companies have no interest in us becoming healthy through nutrition. It is in their financial interest to keep us where we are so they can sell us medications.”

Similar distrust of the government’s dietary recommendations has been expressed by doctors and academics. The following comments, left by a physician on one of the authors’ blogs, are not unusual:

“You and Denise Minger should collaborate on a book about the shoddy analysis put out by hacks like the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee.”

“Sometimes I wonder if people making these statements even took a basic course in biochemistry and physiology.”

Many patients have given up on their health care professionals and turn to Internet sites for advice they trust. This is particularly true of diabetics who find that a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet is not helping them control their blood glucose. As one woman wrote about her experience with a diabetes center:

“I was so frustrated, I quit going to the center for check ups.”

The data suggest a serious problem in science-community interactions which needs to be explored.

Conclusions & recommendations: Our findings document a large number of such cases pointing to the need for public hearings and or conference. The community is not well served by an establishment that refuses to address its critics from within the general population as well as health professionals.

Who says you cannot speak of reason to the Dane and lose your voice? Who says two wrongs don’t make a right?

Posted: October 11, 2011 in Association and Causality, Evidence Based Medicine, low-carbohydrate diet, Tax on FatTags: biochemistry, carbohydrate, dietary guidelines

The King in Hamlet says “you cannot speak of reason to the Dane and lose your voice” and most Americans do feel good about the Danes. We hold to the stereotype that they are friendly folk with a dry sense of humor like Victor Borge. That is why Reuben and Rose Mattus, the Polish-Jewish immigrant ice-cream makers from the Bronx who tried to find an angle that would allow them to compete with Sealtest® and other big guns, picked Häagen-Dazs® as the name for their up-scale ice cream, even including a map of Denmark on the early packaging. (Never mind that there is no Scandinavian language that has the odd-ball collection of foreign-looking spelling; Danish does not have an umlaut and I don’t think any Indo-European language has the combination “zs;” there is Zsa Zsa Gabor, of course, but Hungarian is a Uralic language related only to languages that you never heard of).

The original post here held that the Mattuses would have been very surprised to see that products like their high-butterfat ice cream are now a target of the Danish government which instituted a tax on foods containing saturated fat on October 1 of 2011. The tax, I am happy to say has since been repealed. In a brilliant turn-around that gives a great insight into the mind of the tax man, the Times reported that ” the tax raised $216 million in new revenue. To offset the loss of that money, the Legislature plans a small increase in income taxes and the elimination of some deductions.” Get it? They are going to increase taxes to cover the money that they hoped to have, never mind, that the intention was to stop people from buying the stuff that would bring in the revenue.

The original idea for collecting taxes on a number of items including “sugar, fat and tobacco,” came from Jakob Axel Nielsen (right), then Sundhedsminister. A graduate of the law school at Aarhus, Nielsen is reputed to know even more about science than Hizzona’ Michael Bloomberg. The LA Times points out, however, that “for those who may be tempted to call for Nielsen’s job, please note that he stepped down…last year.”

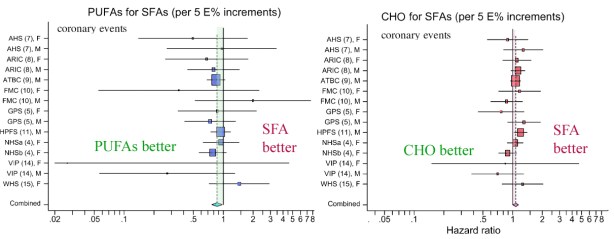

One of the things that is surprising about all this is that, in 2009, a combined Danish and American research group whose senior author was Dr. Marianne Jakobsen of Copenhagen University Hospital published a paper showing that there was virtually no effect of dietary saturated fatty acids (SFAs) on cardiovascular disease. The study was a meta-analysis which means a re-evaluation of many previous studies. The authors concluded that the results “suggest that replacing SFA intake with PUFA (polyunsaturated fatty acid) intake rather than MUFA (monounsaturated fatty acids) or carbohydrate intake prevents CHD (coronary heart disease) over a wide range of intakes.”

As in many nutritional papers, it is worthwhile to actually look at the data. The figure below, from Jakobsen’s paper shows the results from several studies in which the effect of substituting 5 % of energy from SFA with either carbohydrate (CHO) or PUFA or MUFA (not shown here) was measured. The outcome variable is the hazard ratio for incidence of coronary events (heart attack, sudden death). You can think of the hazard ratio as similar to an odds ratio which is what it sounds like: the comparative odds of different possible outcomes. The basic idea is that if 10 people in a group of 100 have a heart attack with saturated fat in their diet, the odds = 10 out of 100 or 1/10. If you now replace 5 % of energy with PUFAs for a different group of 100 and find only 8 people have an event, then the odds for the second group is 8/100 and the odds ratio is 0.8 (8/100 divided by 10/100). If the odds ratio were 1.0, then there would be no benefit either way, no difference if you keep SFAs or replace. So in the first figure below, most of the points are to the left of the point 1.0, suggesting that PUFA is better than SFA but the figure on the right suggests that SFA is better than CHO. But is this real?

You probably noticed that you would have the same odds ratio if the sample sizes were 1000. In other words, a ratio gives relative values and obscures some information. If there were a large number of people and the real numbers were actually 8 and 10, you wouldn’t put much stock in the hazard ratio; decreasing your chances of a low probability event is not a big deal; you double your chances of winning the lottery by buying two tickets. In fact, whereas heart disease is a big killer, if you study a thousand people for 5 years there will be only a small number of coronary events. I discussed this in a previous post, but giving Jakobsen the benefit of the doubt that there were really differences on outcomes, we need to know whether the hazard ratios are really reliable. In this case, Jakobsen showed the variability in the results with “95% confidence intervals,” which are represented by the horizontal bars in the figure.

The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) is a measure of the spread of values around the average. It tells you how reliable the data is. Technically, the term means that if you calculate the size of the interval over and over, 95% of the time the interval will contain the true value. Although not technically precise, you could think of it as meaning that there is a 95% chance of the interval containing the true value.

There is one important point here. It is a statistical rule that if the 95% CI bar crosses the line for hazard ratio = 1.0 then this is taken as indiction that there is no significant difference between the two conditions, in this case, SFAs or a replacement. Looking at the figure from Jakobsen, we are struck by the fact that, in the list of 15 different studies for two replacements, all but one cross the hazard ratio = 1.0 line; one study found that keeping SFAs in the diet provides a lower risk than replacement with carbohydrate. For all the others it was a wash. At this point, one has to ask why a combined value was calculated. How could 15 studies that show nothing add up to a new piece of information. Who says two wrongs, or even 15, can’t make a right? The remarkable thing is that some of the studies in this meta-analysis are more than 20 years old. How could these have had so little impact? Why did we keep believing that saturated fat was bad?

Taxing Saturated Fat.

Now the main thing that taxes do is bring in money. That’s why it is not a good idea to tie it to a health strategy unless you are really sure (as in the case of cigarettes). For one thing, there is something contradictory (or pessimistic) about trying to raise money from a behavior that you want people to stop doing. In any case, given that during the epidemic of obesity and diabetes, saturated fat intake went down (for men, the absolute amount went down by 14%), and that there was no effect on the incidence of heart disease (although survival was better due to treatment), there is every reason to consider the possibility of unexpected negative outcomes (think margarine and trans-fat). Although now repealed, it is worth considering possible unintended consequences (since the sugar tax is still alive). Suppose that the Danes had reduced consumption of saturated fat but still ate enough to bring in money. And suppose that this had the opposite effect — after all, if you believe the Jakobsen study, substituting carbohydrate for saturated fat will increase cardiovascular risk. So now there would be a revenue stream that was associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease. What would they have done? What would we do? Well, we’d stop it, of course. Yeah, right.

The Nutrition Mess. Lessons from Moneyball.

Posted: September 23, 2011 in Evidence Based Medicine, Lipophobes, low-carbohydrate diet, The Nutrition StoryTags: ADA, baseball, carbohydrate, dietary guidelines, In the face of contradictory evidence, low-fat, nutrition, USDA

Baseball is like church. Many attend. Few understand.

— Leo Durocher.

The movie Moneyball provides an affirmative answer to an important question in literature and drama: can you present a scene and bring out the character of a subject that is boring while, at the same time, not make the presentation boring? The movie, and Michael Lewis’sbook that it is based on, are about baseball and statistics! For fans, baseball is not boring so much as incredibly slow, providing a soothing effect like fishing, interspersed with an occasional big catch. The movie stars Brad Pitt as Billy Beane, the General Manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team in the 1990s. A remarkably talented high school athlete, Billy Beane, for unknown reasons, was never able to play out his potential as an MLB player but, in the end, he had a decisive effect on the game at the managerial level. The question is how the A’s, with one-third of the budget of the Yankees, could have been in the play-offs three years in a row and, in 2001, could win 102 games. The movie is more or less faithful to the book and both are as much about organizations and psychology as about sports. The story was “an example of how an unscientific culture responds, or fails to respond, to the scientific method” and the science is substantially statistical.

In America, baseball is a metaphor for just about everything. Probably because it is an experience of childhood and adolescence, lessons learned from baseball stay with us. Baby-boomers who grew up in Brooklyn were taught by Bobby Thompson’s 1951 home-run, as by nothing later, that life isn’t fair. The talking heads in Ken Burns’s Baseball who found profound meaning in the sport are good examples. Former New York Governor Mario Cuomo’s comments were quite philosophical although he did add the observation that getting hit in the head with a pitched ball led him to go into politics.

One aspect of baseball that is surprising, especially when you consider the money involved, is the extent to which strategy and scouting practices have generally ignored hard scientific data in favor of tradition and lore. Moneyball tells us about group think, self-deception and adherence to habit in the face of science. For those of us who a trying to make sense of the field of nutrition, where people’s lives are at stake and where numerous professionals who must know better insist on dogma — low fat, no red meat — in the face of contradictory evidence, baseball provides some excellent analogies.

The real stars of the story are the statistics and the computer or, more precisely, the statistics and computer guys: Bill James an amateur analyzer of baseball statistics and Paul DePodesta, assistant General Manager of the A’s who provided information about the real nature of the game and how to use this information. James self-published a photocopied book called 1977 baseball abstract: featuring 18 categories of statistical information you just can’t find anywhere else. The book was not just about statistics but was in fact a critique of traditional statistics pointing out, for example, that the concept of an “error;” was antiquated, deriving from the early days of gloveless fielders and un-groomed playing fields of the 1850s. In modern baseball, “you have to do something right to get an error; even if the ball is hit right at you, and you were standing in the right place to begin with.” Evolving rapidly, the Abstracts became a fixture of baseball life and are currently the premium (and expensive) way to obtain baseball information.

It is the emphasis on statistics that made people doubt that Moneyball could be made into a movie and is probably why they stopped shooting the first time around a couple of years ago. Also, although Paul DePodesta (above) is handsome and athletic, Hollywood felt that they should cast him as an overweight geek type played by Jonah Hill. All of the characters in the film have the names of the real people except for DePodesta “for legal reasons,” he says. Paul must have no sense of humor.

The important analogy with nutrition research and the continuing thread in this blog, is that it is about the real meaning of statistics. Lewis recognized that the thing that James thought was wrong with the statistics was that they

“made sense only as numbers, not as a language. Language, not numbers, is what interested him. Words, and the meaning they were designed to convey. ‘When the numbers acquire the significance of language,’ he later wrote, ‘they acquire the power to do all the things which language can do: to become fiction and drama and poetry … . And it is not just baseball that these numbers through a fractured mirror, describe. It is character. It is psychology, it is history, it is power and it is grace, glory, consistency….’”

By analogy, it is the tedious comparison of quintiles from the Harvard School of Public Health proving that white rice will give you diabetes but brown rice won’t or red meat is bad but white meat is not, odds ratio = 1.32. It is the bloodless, mindless idea that if the computer says so, it must be true, regardless of what common sense tells you. What Bill James and Paul DePodesta brought to the problem was understanding that the computer will only give you a meaningful answer if you ask the right question; asking what behaviors accumulated runs and won ball games, not which physical characteristics — runs fast, looks muscular — that seem to go with being a ball player… the direct analog of “you are what you eat,” or the relative importance of lowering you cholesterol vs whether you actually live or die.

As early as the seventies, the computer had crunched baseball stats and come up with clear recommendations for strategy. The one I remember, since it was consistent with my own intuition, was that a sacrifice bunt was a poor play; sometimes it worked but you were much better off, statistically, having every batter simply try to get a hit. I remember my amazement at how little effect the computer results had on the frequency of sacrifice bunts in the game. Did science not count? What player or manager did not care whether you actually won or lost a baseball game. The themes that are played out in Moneyball, is that tradition dies hard and we don’t like to change our mind even for our own benefit. We invent ways to justify our stubbornness and we focus on superficial indicators rather than real performance and sometimes we are just not real smart.

Among the old ideas, still current, was that the batting average is the main indicator of a batter’s strength. The batting average is computed by considering that a base-on-balls is not an official at bat whereas a moments thought tells you that the ability to avoid bad pitches is an essential part of the batter’s skill. Early on, even before he was hired by Billy Beane, Paul DePodesta had run the statistics from every twentieth century baseball team. There were only two offensive statistics that were important for a winning team percentage: on-base percentage (which included walks) and slugging percentage. “Everything else was far less important.” These numbers are now part of baseball although I am not enough of a fan to know the extent to which they are still secondary to the batting average.

One of the early examples of the conflict between tradition and science was the scouts refusal to follow up on the computer’s recommendation to look at a fat, college kid named Kevin Youkilis who would soon have the second highest on-base percentage after Barry Bonds. “To Paul, he’d become Euclis: the Greek god of walks.”

The big question in nutrition is how the cholesterol-diet-heart paradigm can persist in the face of the consistent failures of experimental and clinical trials to provide support. The story of these failures and the usurpation of the general field by idealogues has been told many times. Gary Taubes’s Good Calories, Bad Calories is the most compelling and, as I pointed out in a previous post, there seems to have been only one rebuttal, Steinberg’s Cholesterol Wars. The Skeptics vs. the Preponderance of Evidence. At least within the past ten year, a small group have tried to introduce new ideas, in particular that it is excessive consumption of dietary carbohydrate, not dietary fat, that is the metabolic component of the problems in obesity, diabetes and heart disease and have provided extensive, if generally un-referenced, experimental support. An analogous group tried to influence baseball in the years before Billy Beane. Larry Lucchino, an executive of the San Diego Padres described the group in baseball as being perceived as something of a cult and therefore easily dismissed. “There was a profusion of new knowledge and it was ignored.” As described in Moneyball “you didn’t have to look at big-league baseball very closely to see its fierce unwillingness to rethink any it was as if it had been inoculated against outside ideas.”

“Grady Fuson, the A’s soon to be former head of scouting, had taken a high school pitcher named Jeremy Bonderman and the kid had a 94 mile-per-hour fastball, a clean delivery, and a body that looked as if it had been created to wear a baseball uniform. He was, in short, precisely the kind of pitcher Billy thought he had trained the scouting department to avoid…. Taking a high school pitcher in the first round — and spending 1.2 million bucks to sign — that was exactly this sort of thing that happened when you let scouts have their way. It defied the odds; it defied reason. Reason, even science, was what Billy Beane was intent on bringing to baseball.”

The analogy is to the deeply ingrained nutritional tradition, the continued insistence on cholesterol and dietary fat that are assumed to have evolved in human history in order to cause heart disease. The analogy is the persistence of the lipophobes, in the face of scientific results showing, at every turn, that these were bad ideas, that, in fact, dietary saturated fat does not cause heart disease. It leads, in the end, to things like Steinberg’s description of the Multiple risk factor intervention trial. (MRFIT; It’s better not to be too clever on acronyms lest the study really bombs out): “Mortality from CHD was 17.9 deaths per 1,000 in the [intervention] group and 19.3 per 1,000 in the [control] group, a statistically nonsignificant difference of 7.1%”). Steinberg’s take on MRFIT:

“The study failed to show a significant decrease in coronary heart disease and is often cited as a negative study that challenges the validity of the lipid hypothesis. However, the difference in cholesterol level between the controls and those on the lipid lowering die was only about 2 per cent. This was clearly not a meaningful test of the lipid hypothesis.”

In other words, cholesterol is more important than outcome or at least a “diet designed to lower cholesterol levels, along with advice to stop smoking and advice on exercise” may still be a good thing.

Similarly, the Framingham study which found a strong association between cholesterol and heart disease found no effect of dietary fat, saturated fat or cholesterol on cardiovascular disease. Again, a marker for risk is more important than whether you get sick. “Scouts” who continued to look for superficial signs and ignore seemingly counter-intuitive conclusions from the computer still hold sway on the nutritional team.

“Grady had no way of knowing how much Billy disapproved of Grady’s most deeply ingrained attitude — that Billy had come to believe that baseball scouting was at roughly the same stage of development in the twenty-first century as professional medicine had been in the eighteenth.”

Professional medicine? Maybe not the best example.

What is going on here? Physicians, like all of us, are subject to many reinforcers but for humans power and control are usually predominant and, in medicine, that plays out most clearly in curing the patient. Defeating disease shines through even the most cynical analysis of physician’s motivations. And who doesn’t play baseball to win. “The game itself is a ruthless competition. Unless you’re very good, you don’t survive in it.”

Moneyball describes a “stark contrast between the field of play and the uneasy space just off it, where the executives in the Scouts make their livings.” For the latter, read the expert panels of the American Heat Association and the Dietary Guidelines committee, the Robert Eckels who don’t even want to study low carbohydrate diets (unless it can be done in their own laboratory with NIH money). In this

“space just off the field of play there really is no level of incompetence that won’t be tolerated. There are many reasons for this, but the big one is that baseball has structured itself less as a business and as a social club. The club includes not only the people who manage the team but also in a kind of women’s auxiliary many of the writers and commentators to follow and purport to explain. The club is selective, but the criteria for admission and retention and it is there many ways to embarrass the club, but being bad at your job isn’t one of them. The greatest offense a club member can commit is not ineptitude but disloyalty.”

The vast NIH-USDA-AHA social club does not tolerate dissent. And the media, WebMD, Heart.org and all the networks from ABCNews to Huffington Post will be there to support the club. The Huffington Post, who will be down on the President of the United States in a moment, will toe the mark when it comes to a low carbohydrate story.

The lessons from money ball are primarily in providing yet another precedent for human error, stubbornness and, possibly even stupidity, even in an area where the stakes are high. In other words, the nutrition mess is not in our imagination. The positive message is that there is, as they say in political science, validator satisfaction. Science must win out. The current threat is that the nutritional establishment is, as I describe it, slouching toward low-carb, doing small experiments, and easing into a position where they will say that they never were opposed to the therapeutic value of carbohydrate restriction. A threat because they will try to get their friends funded to repeat, poorly, studies that have already been done well. But that is another story, part of the strange story of Medicineball.

Portion Control and the Language of Food.

Posted: September 5, 2011 in Dietary Fiber, Intention to Treat, low-carbohydrate diet, The Nutrition Story, USDA Dietary GuidelinesTags: carbohydrate, dietary guidelines, low carbohydrate, USDA

“Portion Control” is a popular buzz-word in nutrition. It has a serious and somewhat quantitative sound as if it were recently discovered and transcends what it really means which is, of course, self-control. Self-control has been around for long time and has a poor history as a dieting strategy. Lip service is paid to how we no longer think that overeating means that you are a bad person but “portion control” is just the latest version of the moralistic approach to dieting; the sense of deprivation that accompanies traditional diets may be one of the greatest barriers to success. Getting away from this attitude is probably the main psychological benefit of low-carbohydrate diets. “Eat all the meat you want” sounds scary to the blue-stockings at the USDA but most people who actually use such diets know that the emphasis is on “want” and by removing the nagging, people usually find that they have very little desire to clean their plate and don’t eat any more meat than they ever did. Coupled with the satiety of fat and protein compared to carbohydrate, this is surely a major factor in the success of carbohydrate restriction. In the big comparison trials, the low-fat trials are constrained to fix calories while the low-carbohydrate group is allowed to eat ad-libitum, and the two groups usually come out about the same total calories.

On the other hand, there is an obvious benefit to having a lean and hungry feel if not look and, as Woody Allen might have put it: eating less is good if only for caloric reasons. So, one tactic in a low carbohydrate diet is to eat a small portion — say, one fried egg, a small hamburger — and then see if you are still hungry before having the second or third portion which while not forbidden, is also not required. The longer you wait between portions, the more satiety sets in.

Intention-to-treat II: Foster, et al: Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years

Posted: August 28, 2011 in Evidence Based Medicine, Intention to Treat, low-carbohydrate diet, The Nutrition StoryTags: carbohydrate, dietary guidelines, In the face of contradictory evidence, JAMA, low-fat, nutrition, statistics

“Doctors prefer large studies that are bad to small studies that are good.”

— anon.

The paper by Foster and coworkers entitled Weight and Metabolic Outcomes After 2 Years on a Low-Carbohydrate Versus Low-Fat Diet, published in 2010, had a surprisingly limited impact, especially given the effect of their first paper in 2003 on a one-year study. I have described the first low carbohydrate revolution as taking place around that time and, if Gary Taubes’s article in the New York Times Magazine was the analog of Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, Foster’s 2003 paper was the shot hear ’round the world.

The paper showed that the widely accepted idea that the Atkins diet, admittedly good for weight loss, was a risk for cardiovascular disease, was not true. The 2003 Abstract said “The low-carbohydrate diet was associated with a greater improvement in some risk factors for coronary heart disease.” The publication generated an explosive popularity of the Atkins diet, ironic in that Foster had said publicly that he undertook the study in order to “once and for all,” get rid of the Atkins diet. The 2010 paper by extending the study to 2 years would seem to be very newsworthy. So what was wrong? Why is the new paper more or less forgotten? Two things. First, the paper was highly biased and its methods were so obviously flawed — obvious even to the popular press — that it may have been a bit much even for the media. It remains to be seen whether it will really be cited but I will suggest here that it is a classic in misleading research and in the foolishness of intention-to-treat (ITT).