In the last post, I had proclaimed a victory for dietary carbohydrate restriction or, more precisely, recognition of its explicit connection with cell signaling. I had anointed the BMC Washington meeting as the historic site for this grand synthesis. It may have been a matter of perception — many researchers in carbohydrate restriction entered the field precisely because it came from the basic biochemistry where the idea was that the key player was the hormone insulin and glucose was the major stimulus for pancreatic secretion of insulin. We had largely ignored the hook-up with cell-biology because of the emphasis on calorie restriction, and it may have only needed getting everybody in the same room to see that the role of insulin in cancer was not separate from its role in carbohydrate restriction. (more…)

Posts Tagged ‘carbohydrate’

Suddenly last summer. Part II

Posted: October 2, 2012 in Cancer, Cell Signaling, low-carbohydrate dietTags: biochemistry, carbohydrate, cell biology, insulin, low carbohydrate, nutrition

Making Americans Afraid of Meat.

Posted: May 13, 2012 in Association and Causality, Crisis in Nutrition, Red Meat, saturated fatTags: carbohydrate, Meat Intake and Mortality, red meat,, statistics

TIME: You’re partnering with, among others, Harvard University on this. In an alternate Lady Gaga universe, would you have liked to have gone to Harvard?

Lady Gaga: I don’t know. I am going to Harvard today. So that’ll do.

— Belinda Luscombe, Time Magazine, March 12, 2012

There was a sense of déja-vu about the latest red meat scare and I thought that my previous post as well as those of others had covered the bases but I just came across a remarkable article from the Harvard Health Blog. It was entitled “Study urges moderation in red meat intake.” It describes how the “study linking red meat and mortality lit up the media…. Headline writers had a field day, with entries like ‘Red meat death study,’ ‘Will red meat kill you?’ and ‘Singing the blues about red meat.”’

What’s odd is that this is all described from a distance as if the study by Pan, et al (and likely the content of the blog) hadn’t come from Harvard itself but was rather a natural phenomenon, similar to the way every seminar on obesity begins with a slide of the state-by-state development of obesity as if it were some kind of meteorologic event.

When the article refers to “headline writers,” we are probably supposed to imagine sleazy tabloid publishers like the ones who are always pushing the limits of first amendment rights in the old Law & Order episodes. The Newsletter article, however, is not any less exaggerated itself. (My friends in English Departments tell me that self-reference is some kind of hallmark of real art). And it is not true that the Harvard study was urging moderation. In fact, it is admitted that the original paper “sounded ominous. Every extra daily serving of unprocessed red meat (steak, hamburger, pork, etc.) increased the risk of dying prematurely by 13%. Processed red meat (hot dogs, sausage, bacon, and the like) upped the risk by 20%.” That is what the paper urged. Not moderation. Prohibition. Who wants to buck odds like that? Who wants to die prematurely?

It wasn’t just the media. Critics in the blogosphere were also working over-time deconstructing the study. Among the faults that were cited, a fault common to much of the medical literature and the popular press, was the reporting of relative risk.

The limitations of reporting relative risk or odds ratio are widely discussed in popular and technical statistical books and I ran through the analysis in the earlier post. Relative risk destroys information. It obscures what the risks were to begin with. I usually point out that you can double your odds of winning the lottery if you buy two tickets instead of one. So why do people keep doing it? One reason, of course, is that it makes your work look more significant. But, if you don’t report the absolute change in risk, you may be scaring people about risks that aren’t real. The nutritional establishment is not good at facing their critics but on this one, they admit that they don’t wish to contest the issue.

Nolo Contendere.

“To err is human, said the duck as it got off the chicken’s back”

— Curt Jürgens in The Devil’s General

Having turned the media loose to scare the American public, Harvard now admits that the bloggers are correct. The Health NewsBlog allocutes to having reported “relative risks, comparing death rates in the group eating the least meat with those eating the most. The absolute risks… sometimes help tell the story a bit more clearly. These numbers are somewhat less scary.” Why does Dr. Pan not want to tell the story as clearly as possible? Isn’t that what you’re supposed to do in science? Why would you want to make it scary?

The figure from the Health News Blog:

|

Deaths per 1,000 people per year |

||

| 1 serving unprocessed meat a week | 2 servings unprocessed meat a day | |

| Women |

7.0 |

8.5 |

| 3 servings unprocessed meat a week | 2 servings unprocessed meat a day | |

| Men |

12.3 |

13.0 |

Unfortunately, the Health Blog doesn’t actually calculate the absolute risk for you. You would think that they would want to make up for Dr. Pan scaring you. Let’s calculate the absolute risk. It’s not hard.Risk is usually taken as probability, that is, number cases divided by total number of participants. Looking at the men, the risk of death with 3 servings per week is equal to the 12.3 cases per 1000 people = 12.3/1000 = 0.1.23 = 1.23 %. Now going to 14 servings a week (the units in the two columns of the table are different) is 13/1000 = 1.3 % so, for men, the absolute difference in risk is 1.3-1.23 = 0.07, less than 0.1 %. Definitely less scary. In fact, not scary at all. Put another way, you would have to drastically change the eating habits (from 14 to 3 servings) of 1, 429 men to save one life. Well, it’s something. Right? After all for millions of people, it could add up. Or could it? We have to step back and ask what is predictable about 1 % risk. Doesn’t it mean that if a couple of guys got hit by cars in one or another of the groups whether that might not throw the whole thing off? in other words, it means nothing.

Observational Studies Test Hypotheses but the Hypotheses Must be Testable.

It is commonly said that observational studies only generate hypotheses and that association does not imply causation. Whatever the philosophical idea behind these statements, it is not exactly what is done in science. There are an infinite number of observations you can make. When you compare two phenomena, you usually have an idea in mind (however much it is unstated). As Einstein put it “your theory determines the measurement you make.” Pan, et al. were testing the hypothesis that red meat increases mortality. If they had done the right analysis, they would have admitted that the test had failed and the hypothesis was not true. The association was very weak and the underlying mechanism was, in fact, not borne out. In some sense, in science, there is only association. God does not whisper in our ear that the electron is charged. We make an association between an electron source and the response of a detector. Association does not necessarily imply causality, however; the association has to be strong and the underlying mechanism that made us make the association in the first place, must make sense.

What is the mechanism that would make you think that red meat increased mortality. One of the most remarkable statements in the original paper:

“Regarding CVD mortality, we previously reported that red meat intake was associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease2, 14 and saturated fat and cholesterol from red meat may partially explain this association. The association between red meat and CVD mortality was moderately attenuated after further adjustment for saturated fat and cholesterol, suggesting a mediating role for these nutrients.” (my italics)

This bizarre statement — that saturated fat played a role in increased risk because it reduced risk— was morphed in the Harvard News Letters plea bargain to “The authors of the Archives paper suggest that the increased risk from red meat may come from the saturated fat, cholesterol, and iron it delivers;” the blogger forgot to add “…although the data show the opposite.” Reference (2) cited above had the conclusion that “Consumption of processed meats, but not red meats, is associated with higher incidence of CHD and diabetes mellitus.” In essence, the hypothesis is not falsifiable — any association at all will be accepted as proof. The conclusion may be accepted if you do not look at the data.

The Data

In fact, the data are not available. The individual points for each people’s red meat intake are grouped together in quintiles ( broken up into five groups) so that it is not clear what the individual variation is and therefore what your real expectation of actually living longer with less meat is. Quintiles are some kind of anachronism presumably from a period when computers were expensive and it was hard to print out all the data (or, sometimes, a representative sample). If the data were really shown, it would be possible to recognize that it had a shotgun quality, that the results were all over the place and that whatever the statistical correlation, it is unlikely to be meaningful in any real world sense. But you can’t even see the quintiles, at least not the raw data. The outcome is corrected for all kinds of things, smoking, age, etc. This might actually be a conservative approach — the raw data might show more risk — but only the computer knows for sure.

Confounders

“…mathematically, though, there is no distinction between confounding and explanatory variables.”

— Walter Willett, Nutritional Epidemiology, 2o edition.

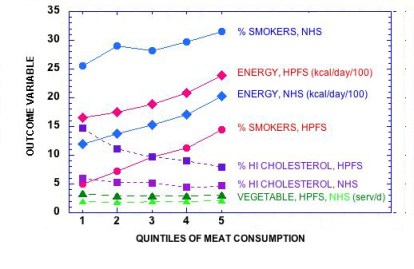

You make a lot of assumptions when you carry out a “multivariate adjustment for major lifestyle and dietary risk factors.” Right off , you assume that the parameter that you want to look at — in this case, red meat — is the one that everybody wants to look at, and that other factors can be subtracted out. However, the process of adjustment is symmetrical: a study of the risk of red meat corrected for smoking might alternatively be described as a study of the risk from smoking corrected for the effect of red meat. Given that smoking is an established risk factor, it is unlikely that the odds ratio for meat is even in the same ballpark as what would be found for smoking. The figure below shows how risk factors follow the quintiles of meat consumption. If the quintiles had been derived from the factors themselves we would have expected even better association with mortality.

The key assumption is that the there are many independent risk factors which contribute in a linear way but, in fact, if they interact, the assumption is not appropriate. You can correct for “current smoker,” but biologically speaking, you cannot correct for the effect of smoking on an increased response to otherwise harmless elements in meat, if there actually were any. And, as pointed out before, red meat on a sandwich may be different from red meat on a bed of cauliflower puree.

This is the essence of it. The underlying philosophy of this type of analysis is “you are what you eat.” The major challenge to this idea is that carbohydrates, in particular, control the response to other nutrients but, in the face of the plea of nolo contendere, it is all moot.

Who paid for this and what should be done.

We paid for it. Pan, et al was funded in part by 6 NIH grants. (No wonder there is no money for studies of carbohydrate restriction). It is hard to believe with all the flaws pointed out here and, in the end, admitted by the Harvard Health Blog and others, that this was subject to any meaningful peer review. A plea of no contest does not imply negligence or intent to do harm but something is wrong. The clear attempt to influence the dietary habits of the population is not justified by an absolute risk reduction of less than one-tenth of one per cent, especially given that others have made the case that some part of the population, particularly the elderly may not get adequate protein. The need for an oversight committee of impartial scientists is the most important conclusion of Pan, et al. I will suggest it to the NIH.

Saturated Fat. On your Plate or in your Blood?

Posted: February 22, 2012 in low-carbohydrate diet, saturated fat, triglycerides, Volek-Westman principleTags: biochemistry, carbohydrate, low carbohydrate, saturated fat, Volek-Westman principle

(Answers to last week’s organic puzzler at the end of this post).

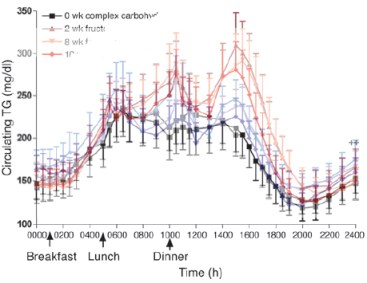

One of the more remarkable results from Jeff Volek’s laboratory in the past few years was the demonstration that when the blood of volunteers was assayed for saturated fatty acids (SFA), those subjects who had been on a very low-carbohydrate diet had lower levels than those on an isocaloric low-fat diet. This, despite the fact that the low-carbohydrate diet had three times the amount of saturated fat as the low-fat diet. How is this possible? What happened to the saturated fat in the low-carbohydrate diet? Well, that’s what metabolism does. The saturated fat in the low-carbohydrate arm was oxidized while (the real impact of the study) the low-fat arm is making new saturated fatty acid. Volek’s former student Cassandra Forsythe extended the idea by showing how, even under eucaloric conditions (no weight loss) dietary fat has relatively small impact on plasma fat.

The essential point of what I now call the Volek-Westman principle — we should be speaking of basic principles because the idea is more important than specific diets where it is impossible to get any agreement on definitions — the principle is that carbohydrate, directly or indirectly through insulin and other hormones, controls what happens to ingested (or stored) fatty acids. The motto of the Nutrition & Metabolism Society is: “A high fat diet in the presence of carbohydrate is different than a high fat diet in the presence of low carbohydrate.” Widely attributed to me, it is almost certainly something I once said although it has been said by others and the studies from Volek’s lab give you the most telling evidence.

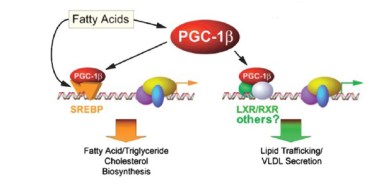

The question is critical. Whereas the scientific evidence now establishes that dietary saturated fat has no effect on cardiovascular disease, obesity or anything else, plasma saturated fatty acids can be a cellular signal and if you study the effect of dietary saturated fatty acids under conditions where carbohydrate is high and/or in rodents where plasma fat better correlates with dietary fat, then you will confuse plasma fat with dietary fat. An important study identified potential cellular elements in control of gene transcription that bear on lipid metabolism.

The question is critical. Whereas the scientific evidence now establishes that dietary saturated fat has no effect on cardiovascular disease, obesity or anything else, plasma saturated fatty acids can be a cellular signal and if you study the effect of dietary saturated fatty acids under conditions where carbohydrate is high and/or in rodents where plasma fat better correlates with dietary fat, then you will confuse plasma fat with dietary fat. An important study identified potential cellular elements in control of gene transcription that bear on lipid metabolism.

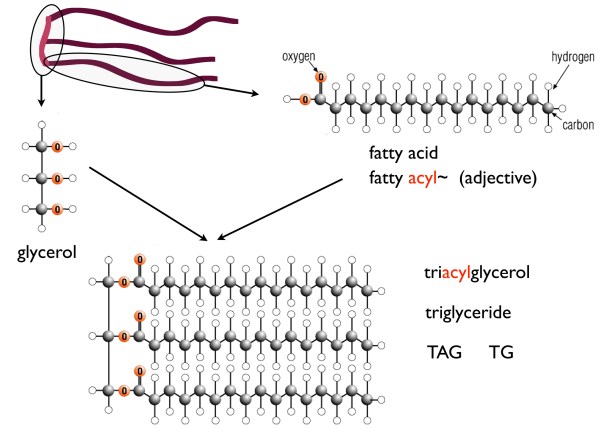

So, it is important to know about plasma saturated fatty acids. First, recall that strictly speaking there are only saturated fatty acids (SFA) — this is explained in detail in an earlier post. What is called saturated fats simply mean those fats that have a high percentage of SFAs — things that we identify as “saturated fats,” like butter, are usually only 50 % saturated fatty acids (coconut oil is probably the only fat that is almost entirely saturated fatty acids but because they are medium chain length, they are usually considered a special case).

In Volek’s study, 40 overweight subjects were randomly assigned either to a carbohydrate-restricted diet (abbreviated CRD; %CHO:fat:protein = 12:59:28) or to a low fat diet, (LFD; %CHO:fat:protein = 56:24:20). The group was unusual in that they were all overweight would be characterized as having metabolic syndrome, in particular they all had, atherogenic dyslipidemia, which is the term given to a poor lipid profile (high triacylglycerol (TAG), low HDL-C, high small-dense LDL (so-called pattern B)). Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is the predisposition to CVD and diabetes and is characterized by the constellation of overweight, atherogenic dyslipidemia and, by now, a dozen other markers.

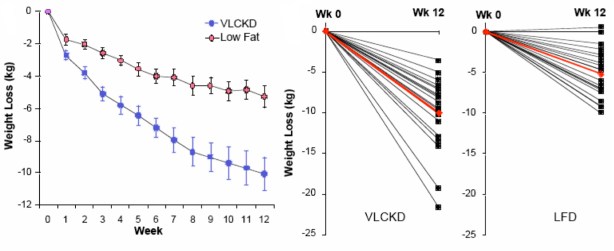

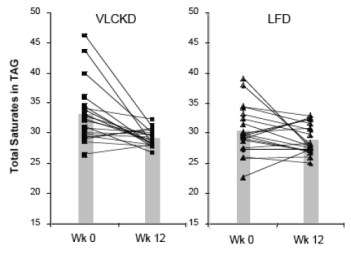

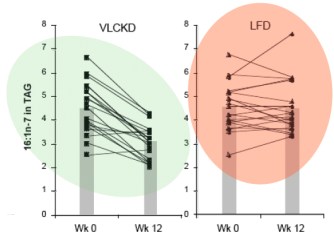

The paper is one of the more striking for the differences in weight loss between two diet regimens. Although participants were not specifically counseled to reduce calories, there was a reduction in total caloric intake in both two groups. The response in weight loss, however, due to the difference in macronutrient composition, was dramatically different in the two groups. The CRD group (labelled as very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet (VLCKD) in the figure) lost twice as much weight on average as the low-fat controls despite the similar caloric intake. Although there was substantial individual variation, 9 of 20 subjects in the CRD (VLCKD) group lost 10% of their starting weight. more than that lost by any of the subjects in the LFD group. In fact, nobody following the LFD lost as much weight as the average for the low-carbohydrate group and, unlike George Bray’s demonstration of caloric inefficiency, whole body fat mass was where the major differences between the CRD (VLCKD) and LF appeared (5.7 kg vs 3.7 kg). Of significance is the observation that fat mass in the abdominal region decreased more in subjects on the CRD than in subjects following the LFD (-828 g vs -506 g). This is one of the more dramatic effects of carbohydrate restriction on weight loss but many have preceded it and these have been frequently criticized for increasing the amount of saturated fat (whether or not any particular study actually increased saturated fat). Although the original “concern” was that this would lead to increased plasma cholesterol, eventually saturated fat became a generalized villain and, insofar as any science was involved, the effects of plasma saturated fat were assumed to be due to dietary saturated fat. The outcome of Volek’s study was surprising. Surprising because the effect was so clear cut (no statistics needed) and because an underlying mechanism could explain the results.

Saturated Fat

The dietary intake of saturated fat for the people on the VLCKD (36 g/day) was threefold higher than that of the people on the LFD (12 g/day). When the relative proportions of circulating SFAs in the triglyceride and cholesterol ester fractions were determined, they were actually lower in the low carb group. Seventeen of 20 subjects on the CRD (VLCKD) showed a decrease in total saturates (the others had low values at baseline) in comparison to half of the subjects consuming the LFD had a decrease in saturates. When the absolute fasting TAG levels are taken into account (low carbohydrate diets reliably reduce TAB=G), the absolute concentration of total saturates in plasma TAG was reduced by 57% in the low carbohydrate arm compared to 24% reduction in the low fat arm who had, in fact, reduced their saturated fat intake. One of the saturated fatty acids of greatest interest was palmitic acid or, in chemical short-hand, 16:0 (16 means that there are 16 carbons and 0 means there are no double bonds, that is, no unsaturation).

The dietary intake of saturated fat for the people on the VLCKD (36 g/day) was threefold higher than that of the people on the LFD (12 g/day). When the relative proportions of circulating SFAs in the triglyceride and cholesterol ester fractions were determined, they were actually lower in the low carb group. Seventeen of 20 subjects on the CRD (VLCKD) showed a decrease in total saturates (the others had low values at baseline) in comparison to half of the subjects consuming the LFD had a decrease in saturates. When the absolute fasting TAG levels are taken into account (low carbohydrate diets reliably reduce TAB=G), the absolute concentration of total saturates in plasma TAG was reduced by 57% in the low carbohydrate arm compared to 24% reduction in the low fat arm who had, in fact, reduced their saturated fat intake. One of the saturated fatty acids of greatest interest was palmitic acid or, in chemical short-hand, 16:0 (16 means that there are 16 carbons and 0 means there are no double bonds, that is, no unsaturation).

So how could this happen? The low fat group reduced their SFA intake by one-third, yet had more SFA in their blood than the low-carbohydrate group who had actually increased intake. Well, we need to look at the next thing in metabolism.

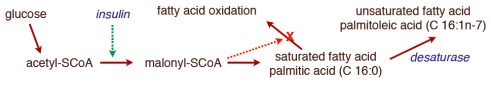

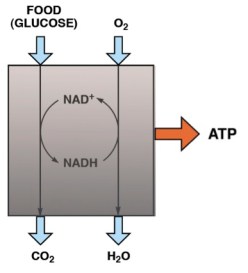

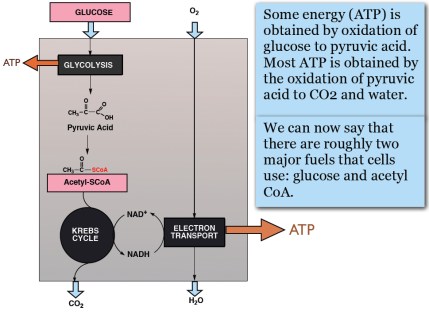

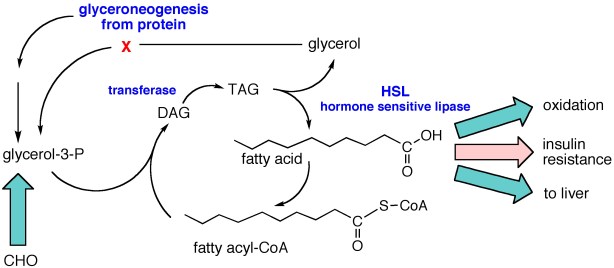

In the post on An Introduction to Metabolism, we made the generalization that there were roughly two kinds of fuel, glucose and acetyl-CoA (the two carbon derivative of acetic acid). The big principle in metabolism was that you could make acetyl-CoA from glucose, but (with some exceptions) you couldn’t make glucose from acetyl-CoA, or more generally, you can make fat from glucose but you can’t make glucose from fat. How do you make fat from glucose? Part of the picture is making new fatty acids, the process known as De Novo Lipogenesis (DNL) or more accurately de novo fatty acid synthesis. The mechanism then involves successively patching together two carbon acetyl-CoA units until you reach the chain length of 16 carbons, palmitic acid. The first step is formation of a three carbon compound, malonyl-CoA, a process which is under the control of insulin. Malonyl-CoA starts the process of DNL but simultaneously prevents oxidation of any fatty acid since, if you are making it, you don’t want to burn it. This can be further processed, among other things, can be elongated to stearic acid (18:0). So this is a reasonable explanation for the increased saturated fatty acid in the low-fat group: the higher carbohydrate diet has higher insulin levels on average, encouraging diversion of calories into fatty acid synthesis and repressing oxidation. How could this be tested?

It turns out that, in addition to elongation, the palmitic acid can be desaturated to make the unsaturated fatty acid, palmitoleic acid (16:1-n7, 16 carbons, one unsaturation at carbon 7) and the same enzyme that catalyzes this reaction will convert stearic acid (18:0) to the unsaturated fatty acid oleic acid (18:1n-7). The enzyme is named for the second reaction stearoyl desaturase-1 (SCD-1; medical students always hate seeing a “-1” since they know 2 and 3 may will have to be learned although, in this case, they are less important). SCD-1 is a membrane-bound enzyme and it seems that it is not swimming around the cell looking for fatty acids but is, rather, closely tied to DNL, that is, it preferentially de-saturates newly formed palmitic acid to palmitoleic acid.

It turns out that, in addition to elongation, the palmitic acid can be desaturated to make the unsaturated fatty acid, palmitoleic acid (16:1-n7, 16 carbons, one unsaturation at carbon 7) and the same enzyme that catalyzes this reaction will convert stearic acid (18:0) to the unsaturated fatty acid oleic acid (18:1n-7). The enzyme is named for the second reaction stearoyl desaturase-1 (SCD-1; medical students always hate seeing a “-1” since they know 2 and 3 may will have to be learned although, in this case, they are less important). SCD-1 is a membrane-bound enzyme and it seems that it is not swimming around the cell looking for fatty acids but is, rather, closely tied to DNL, that is, it preferentially de-saturates newly formed palmitic acid to palmitoleic acid.

There is very little palmitoleic acid in the diet so its presence in the blood is an indication of SCD-1 activity. The data show a 31% decrease in palmitoleic acid (16:1n-7) in the blood of subjects on the low-carb arm with little overall change in the average response in the low fat group. Saturated fat, in your blood or on your plate?

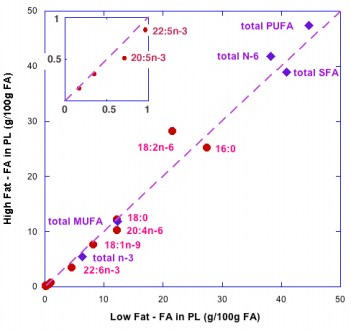

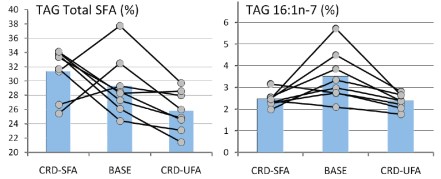

Forsythe’s paper extended the work by putting men on two different weight-maintaining low-carbohydrate diets for 6 weeks. One of the diets was designed to be high in SFA (high in dairy fat and eggs), and the other, was designed to be higher in unsaturated fat from both polyunsaturated (PUFA) and monounsaturated (MUFA) fatty acids (high in fish, nuts, omega-3 enriched eggs, and olive oil). The relative percentages of SFA:MUFA: PUFA were, for the SFA-carbohydrate-restricted diet, 31: 21:5, and for the UFA diet, 17:25:15. The results showed that the major changes in plasma SFA and MUFA were in the plasma TAG fraction although probably much less than might be expected given the nearly two-fold difference in dietary saturated fat and, as the authors point out: “the most striking finding was the lack of association between dietary SFA intake and plasma SFA concentrations.”

So although it is widely said that the type of fat is more important than the amount, the type is not particularly important. But, what about the amount? A widely cited paper by Raatz, et al. suggested, as indicated by the title, that ‘‘Total fat intake modifies plasma fatty acid composition in humans”, but the data in the paper shows that differences between high fat and low fat were in fact minimal (figure below).

So although it is widely said that the type of fat is more important than the amount, the type is not particularly important. But, what about the amount? A widely cited paper by Raatz, et al. suggested, as indicated by the title, that ‘‘Total fat intake modifies plasma fatty acid composition in humans”, but the data in the paper shows that differences between high fat and low fat were in fact minimal (figure below).

The bottom line is that distribution of types of fatty acid in plasma is more dependent on the level of carbohydrate then the level or type of fat. Volek and Forsythe give you a good reason to focus on the carbohydrate content of your diet. What about the type of carbohydrate? In other words, is glycemic index important? Is fructose as bad as they say? We will look at that in a future post in which I will conclude that no change in the type of carbohydrate will ever have the same kind of effect as replacing carbohydrate across the board with fat. I’ll prove it.

====================================================================

Answers to the organic quiz.

Slouching toward Low-Carb. “We Thought of This First.”

Posted: January 3, 2012 in American Diabetes Association, low-carbohydrate diet, Research Integrity, The Nutrition StoryTags: ADA, carbohydrate, diabetes, low carbohydrate, nutrition

The joke in academic circles is that there are three responses to a new idea. First, “This is wrong,” second, “There’s nothing new in this,” and third, the sub-title of this post. Priority in a scientific discovery is fundamental in science, however, and “we thought of this first” is not always that funny. Getting “scooped” can have serous practical consequences like jeopardizing your grant renewal and, if nothing else, most of us are motivated by a desire to solve the problem and don’t like the feeling that, by analogy, somebody came along and filled in our crossword puzzle. In dietary carbohydrate, all three of the responses co-exist. While an army of dietitians is still claiming that people with diabetes need ever more carbohydrate, in the background the low-fat paradigm crumbles and, somewhat along the lines of the predictions in A Future History of Diabetes , the old guard are coming forward to tell us that they have been recommending low-carb all along.

The latest discoverer of the need to reduce dietary carbohydrate is David Jenkins whose recent paper is entitled “Nuts as a Replacement for Carbohydrates in the Diabetic Diet.” [1] The title is crazy enough, following the tradition of getting away from nutrients, that is, well-defined variables, and replacing it with “food,” that is, mixtures of everything. It is, in fact, not really a low carbohydrate study but the experimental design is not the problem. It is the background and rationale for the study which recognizes the disintegration of the low-fat diet paradigm but, at the same time, fails to cite any of the low-carbohydrate studies that have been instrumental in showing the need to replace carbohydrates in the diabetic diet. Given forty years of studies showing the benefits of low carbohydrate diets and forty years of unrestrained attacks on the method, it will be interesting to see how Jenkins shows that it is actually the nutritional establishment that invented carbohydrate restriction.

Disputes over priority are well known in the history of science. Newton’s frequently quoted statement that he had seen farther than others because he had “stood on the shoulders of giants” has been interpreted by some historians as a sarcastic comment aimed at Robert Hooke with whom he had, among other things, a dispute over the priority for the inverse square law (force of gravity varies as the inverse of the square of the distance: F = GmM/g2). Hooke was short and suffered from kyphosis and is assumed not to have shoulders you would profitably stand on.

Even Einstein had trouble. His dispute with the mathematician David Hilbert about priority for the field equations of general relativity (also about gravity) is still going on, a dispute that I prefer to stay out of. Cited by his biographer, Abraham Pais, Einstein had apparently made up the verb to nostracize (nostrazieren) which he accused Hilbert of doing. (He meant that Hilbert had made Einstein’s idea community knowledge. Googling the word gives you only “ostracize” and “Cosa Nostra.”)

It is not the priority dispute, per se — the original low carbohydrate diet is usually attributed to William Banting who published the Letter on Corpulence in 1863, although Brillat-Savarin’s 1825 Physiologie du goût understood the principle. He said that some people were carbophores and admitted to being one himself. It is not just priority but that the people who are now embracing carbohydrate restriction were previously unrestrained in their attacks on the dietary approach and were adamant in denying the strategy to their patients.

David Jenkins: “Nuts.”

In trying to find an appropriate answer to the recent bit of balderdash by the redoubtable Hope Warshaw, Tom Naughton recounted the story of the Battle of the Bulge of WWII. Towards the end of the war, Hitler launched a massive winter attack around the city of Bastogne where, at one point, American Forces were surrounded. When the Germans demanded surrender, the American General, Anthony McAuliffe, sent the one-word reply: “Nuts!” I always thought it was a euphemism and that he actually went “Vice-presidential” as it was called in the last administration, but it turns to have been a common expression with him and he really did write “nuts” which, of course, had to be explained to the German couriers. (There is a “Nuts” Museum in Bastogne commemorating the battle which the Americans won somewhat as described in the movie Patton).

For installation in the Nutritional Nuts Museum and as an example of the current attempts to co-opt carbohydrate restriction, one can hardly beat Jenkins’s recent paper [1].

Richard:…Who knows not that the gentle duke is dead? ….

King Edward: Who knows not he is dead! Who knows he is?

Queen Elizabeth: All-seeing heaven, what a world is this!

— William Shakespeare, Richard III

The trick is to act as if the point you are making is already established. The Abstract of Jenkins study: “Fat intake, especially monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), has been liberalized in diabetic diets to preserve HDL cholesterol and improve glycemic control….” It has? Liberalized by whom? Although the American Diabetes Association guidelines are traditionally all over the place, few would consider that there is any sense of substantial liberalization on replacing carbohydrate with fat from them or any health agency.

“Replacement of carbohydrate by healthy fat … has been increasingly recognized as a possible therapeutic strategy in the treatment of diabetes [2] as concerns emerge over the impact of refined carbohydrate foods in increasing postprandial glycemia and reducing HDL cholesterol.” Reference [2] ((1) in the original) actually “emerged” in 2002 and is ambiguous at best: “Carbohydrate and monounsaturated fat together should provide 60–70% of energy intake.” (It is not my style of humor, but the behavioral therapists call this “shoulding on people.”) The paper admits that the evidence “is based on expert consensus” and contains what might be called the theme song of the American Diabetes Association:

“Sucrose and sucrose-containing food do not need to be restricted by people with diabetes based on a concern about aggravating hyperglycemia. However, if sucrose is included in the food/meal plan, it should be substituted for other carbohydrate sources or, if added, be adequately covered with insulin or other glucose-lowering medication.” (my italics)

In fact, one emerging piece of evidence is Jenkins 2008 study comparing a diet high in cereal with a low glycemic index diet [3]. The glycemic index is a measure of the actual effect of dietary glucose on blood glucose. Pioneered by Jenkins and coworkers, a low-GI diet is based on the same rationale as a low-carbohydrate diet, that glycemic and insulin fluctuations pose a metabolic risk but it emphasizes “the type of carbohydrate,” that is, it is a politically correct form of low-carbohydrate diet and as stated in the 2008 study: “We selected a high–cereal fiber diet treatment for its suggested health benefits for the comparison so that the potential value of carbohydrate foods could be emphasized equally for both high–cereal fiber and low–glycemic index interventions.” (my emphasis) The Conclusion of the 24-week study was: “In patients with type 2 diabetes, 6-month treatment with a low–glycemic index diet resulted in moderately lower HbA1c levels compared with a high–cereal fiber diet.” The figure below shows the results for HbA1c and weight loss and just looking at the figures, the results are certainly modest enough.

By coincidence, on almost the same day, Eric Westman’s group published a study that compared a low glycemic index diet with a true low carbohydrate diet [4]. The studies were comparable in duration and number of subjects and a direct comparison shows the potential of low carbohydrate diets (NOTE: in the figure, the units for the change are those of the individual parameters; an earlier version showed this as % which was an error):

Oddly, neither of these papers are cited in the current study by Jenkins, et al. In fact, according to the paper, the precedents go way back:

“Recently, there has been renewed interest in reducing carbohydrate content in the diet of diabetic patients. In 1994, on the basis of emerging evidence, the American Diabetes Association first suggested the possibility of exchanging dietary carbohydrate for MUFA in dietary recommendations for type 2 diabetes). Although not all studies have shown beneficial effects of MUFAs in diabetes, general interest has persisted, especially in the context of the Mediterranean diet.”

The ADA discovered low carbohydrate diets ? Did my blogpost see it coming, or what? But wait…

“low carbohydrate intakes have also been achieved on the Atkins diet by increasing animal fats and proteins. This influential dietary pattern is reflectedin the relatively lower pre-study carbohydrate intakes of ~ 45% in the current study rather than the 50–60% once recommended.

The researchers in this area might not feel that 45 % carbohydrate has much to do with the Atkins diet but, in any case, it appears not to have been “influential” enough to actually get the studies supporting it cited.

Again: “Fat intake, especially monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), has been liberalized…” but “… the exact sources have not been clearly defined. Therefore, we assessed the effect of mixed nut consumption as a source of vegetable fat on serum lipids and HbA1c in type 2 diabetes.” Therefore? Nuts? That’s going to clearly define the type of MUFA? Nuts have all kinds of nutrients. How do we know that it is the MUFA in the nuts? In fact, the real question is whether any benefit would not be due to the reduction in carbohydrate regardless of what it were replaced with. So what was the benefit? The figure above shows the effect on hemoglobin A1C. As described by the authors:

“The full-nut dose reduced HbA1c by two-thirds of the reduction recognized as clinically meaningful by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (.0.3% absolute HbA1c units) in the development of antihyperglycemic drugs…”

In other words, almost meaningful, and

“the number of participants who achieved an HbA1c concentration of <7% (19 pre-study participants, down to 13 post-study participants) was significantly greater on the nut treatment than on the muffin treatment (20 pre-study participants, remaining at 20 post-study participants…).”

This is some kind of accomplishment but the figure above shows that, in fact, the results were pretty poor. The statistics do show that the “full nut dose” was significantly different from the half-nut dose or the muffin. But is this what you want to know? After all, nobody has an average change in HbA1c. What most of us want to know is the betting odds. If I down all those nuts, what’s the chance that I’ll get better. How many of the people in the full-nut study did better than those in the half-nut study (did the authors not know that this would sound funny?). You can’t tell for sure because this information is buried in the statistics but the overlap of the error bars, highlighted in pink, suggests that not everybody gained anything — in fact, some may have gotten worse.

What kind of benefit is possible in a dietary intervention for people with diabetes? Well, the studies discussed above from Jenkins himself and from Westman show that, with a low-GI diet, it is possible to obtain an average reduction of about 4 %, more than ten times greater than with nuts and with a real low-carbohydrate diet much greater. I have added an inset to the Figure from Jenkins with data from a 2005 study by Yancy, et al. [5]. The red line shows the progress of the mean in Yancy’s studied. If you had diabetes, would you opt for this approach or go for the full-nut dose?

Bibliography

1. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Banach MS, Srichaikul K, Vidgen E, Mitchell S, Parker T, Nishi S, Bashyam B, de Souza R et al: Nuts as a replacement for carbohydrates in the diabetic diet. Diabetes Care 2011, 34(8):1706-1711.

2. Franz MJ, Bantle JP, Beebe CA, Brunzell JD, Chiasson JL, Garg A, Holzmeister LA, Hoogwerf B, Mayer-Davis E, Mooradian AD et al: Evidence-based nutrition principles and recommendations for the treatment and prevention of diabetes and related complications. Diabetes Care 2002, 25(1):148-198.

3. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, McKeown-Eyssen G, Josse RG, Silverberg J, Booth GL, Vidgen E, Josse AR, Nguyen TH, Corrigan S et al: Effect of a low-glycemic index or a high-cereal fiber diet on type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008, 300(23):2742-2753.

4. Westman EC, Yancy WS, Mavropoulos JC, Marquart M, McDuffie JR: The Effect of a Low-Carbohydrate, Ketogenic Diet Versus a Low-Glycemic Index Diet on Glycemic Control in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2008, 5(36).

5. Yancy WS, Jr., Foy M, Chalecki AM, Vernon MC, Westman EC: A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet to treat type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2005, 2:34.

The Patient’s Voice Project. Your Diabetes Story.

Posted: October 30, 2011 in American Diabetes Association, low-carbohydrate diet, The Nutrition StoryTags: ADA, carbohydrate, diabetes, dietary guidelines, low carbohydrate, low-fat

Doctor: Therein the patient must minister to himself.

Macbeth: Throw physic [medicine] to the dogs; I’ll none of it.

— William Shakespeare, Macbeth

The epidemic of diabetes, if it can be contained at all, will probably fall to the efforts of the collective voice of patients and individual dedicated physicians. The complete abdication of responsibility by the American Diabetes Association (sugar is okay if you “cover it with insulin”) and by other agencies and individual experts, and the media’s need to keep market share with each day’s meaningless new epidemiologic breakthrough leaves the problem of explanation of the disease and its treatment in the hands of individuals.

Jeff O’Connell’s recently published Sugar Nation provides the most compelling introduction to what diabetes really means to a patient, and the latest edition of Dr. Bernstein’s encyclopedic Diabetes Solution is the state-of-the art treatment from the patient-turned-physician. Although the nutritional establishment has been able to resist these individual efforts — the ADA wouldn’t even accept ads for Dr. Bernstein’s book in the early editions — practicing physicians are primarily interested in their patients and may not know or care what the expert nutritional panels say. You can send your diabetes story to Michael Turchiano (MTurchiano.PVP@gmail.com) and Jimmy Moore (livinlowcarbman@charter.net) at The Patient’s Voice Project.

The Patient’s Voice Project

The Patient’s Voice Project, which began soliciting input on Friday, is a research study whose results will be presented at the Office of Research Integrity (ORI) conference on Quest for Research Excellence, March 15-16 in Washington, D.C. The conference was originally scheduled for the end of August but there was a conflict with Hurricane Irene.

The Patients Voice Project is an outgrowth of the scheduled talk “Vox Populi,” the text for which is at the end of this post. A major stimulus was also our previous study on the Active Low-Carber Forums, an online support group. The March conference will present a session on “Crisis in Nutrition” that will include the results of the Patient’s Voice Project.

Official Notice from the Scientific Coordinator, Michael Turchiano

The Patient’s Voice Project is an effort to collect first hand accounts of the experience of people with diabetes (type 1 and type 2) with different diets. If you are a person with diabetes and would be willing to share your experiences with diet as a therapy for diabetes, please send information to Michael Turchiano (MTurchiano.PVP@gmail.com) and a copy to Jimmy Moore (livinlowcarbman@charter.net). Please include details of your diets and duration and whether you are willing to be cited by name in any publication.

It is important to point out that, whereas we think that the benefits of carbohydrate restriction have been greatly under-appreciated and under-recommended, the goal is to find out about people’s experiences:both benefits and limitations of different diets. If you have not had good success with low-carbohydrate diets, it is equally important to share these experiences.

- Indicate if you saw a physician or other health provider, what their attitudes were and whether you would be willing to share medical records.

- We are particularly interested in people who have switched diets and had different outcomes.

- Include any relevant laboratory or medical results that you think are relevant but we are primarily interested in your personal reactions to different diets and interaction with physicians and other health providers.

- Finally, please indicate what factors influenced your choices (physician or nutritionist recommendations, information on popular diets(?) or scientific publications).

Thanks for your help. The Patient’s Voice Project will analyze and publish conclusions in popular and scientific journals.

The Survey of the Active Low-Carber Forums

The Active Low-Carber Forums (ALCF) is an on-line support group that was started in 2000. At the time of our survey (2006), it had 86,000 members and currently has more than 130,000. Our original survey asked members of the forum to complete a 27-item questionnaire and to provide a narrative on any other health issues. Some of the narrative answers included in the published paper were as follows:

“I no longer have diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, joint pain, back pain and loss of energy.”

“I started low carbing for diabetes. My 3 month blood sugar was 8.9 when diagnosed. It is now 5.4. My doctor is thrilled with my diabetes control and as a side benefit, I lost all that weight!”

“I’m controlling my diabetes without meds or injecting insulin (with an a1c below 5), my lipid profile has improved, I’ve lost weight, I’ve gained both strength and endurance, and I’ve been able to discontinue one of my blood pressure meds.”

“I have much more energy, fewer colds or other health problems. I was able to go completely off oral diabetes medication.”

The survey covered a number of topics. We found that most respondents had the perception that they ate less food than before their low-carb diet, and most felt that the major change in their diet was a large increase in the consumption of green vegetables and a corresponding large decrease in fruit intake.

Physicians Attitudes in the ALCF survey

The Patient’s Voice Project is likely to tell us as much about physicians, or at least their interaction with patients, as about the patients themselves. We found in the ACLF survey that slightly more than half of the people who responded said that they had consulted a physician. We were surprised that about 55 % said that the physician or other health professional was supportive of their diet. Another 30 % or so fit the category of “did not have an opinion but was encouraging after seeing results.” Only 6 % of responders indicated that “they were discouraging even after I showed good results,” which may be a surprising result depending on your feeling about the rationality of doctors vs hostility to the Atkins diet. Perusal of patients’ opinions on diabetes websites, however, suggests that the story on people with diabetes will not be as encouraging.

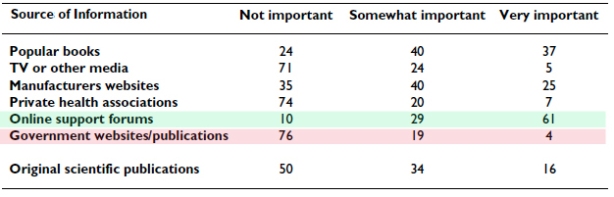

The Survey on Sources of Information

Given the contentious nature of the debate on diet in diabetes therapy, it is not surprising that a group following a low-carb strategy would not put much stock in official sources. The table below shows the breakdown on sources of information from the ALCF survey. Of the half of respondents who said that they relied on original scientific publications, 20 % felt they had generally inadequate access (important articles were not accessible) whereas 61 % felt that access was adequate and were able to see most articles that they wanted.

Voices of Dissatisfaction.

Posts on the ALCLF itself reinforced the idea that official recommendations were not only a limited source of information but that many were perceived as misleading. Typical posts cited in the paper:

“The ‘health experts’ are telling kids and parents the wrong foods to eat. Until we start beating the ‘health experts’ the kids won’t get any better. If health care costs are soaring and type 2 diabetes and its complications, as are most of these expenses why are we not putting a ‘sin’ tax on high glycemic foods to cut consumption and help pay for these cost? Beat the ‘health experts’ – not the kids!”

While I am not a fan of sin taxes, the dissatisfaction is clear, and…

“Until I researched it three years ago – I thought the most important thing was low fat. So I was eating the hell out of low fat products and my health continued to get worse.”

Similarly, the recent article in Diabetes Health by Hope Warshaw http://bit.ly/mYm2O3 with its bizarre recommendation for people with diabetes to increase their carbohydrate intake elicited a number of statements of dissatisfaction:

“Respectfully, this column is not helpful to diabetics and probably dangerous. I am going on 6 years of eating 30-35 carbs/day. My A1c has been in the “non-diabetic” range ever since I went this route and I feel better than I have in years. I am not an exception among the many folks I know who live a good life on restricted carb diets.”

“…carbohydrates are a very dangerous and should be consumed with caution and knowledge. i had awful lipids and blood sugar control on a low fat/high carb diet. now that i have switched to a lower carb diet – all my numbers are superb. and the diet is easy to follow and very satisfying!”

Summary:

The Project is intended to bring out the patient’s perspective on diet as therapy in diabetes. The goals are to document people’s experience in finding the right diet. In particular, we are interested in whether switching to a low-carbohydrate diet provided improvement over the recommended diet typical of the ADA. Or not. We are looking for a narrative that can bring out how people make decisions on choosing a diet and sticking with it: the influences of physicians, the media and personal experimentation. Your diabetes story.

Text of Abstract for the Original ORI Conference

Crisis in Nutrition: IV. Vox Populi

Authors: Tom Naughton, Jimmy Moore, Laura Dolson

Objective: Blogs and other social media provide insights into how a growing share of the population views the current state of nutrition science and the official dietary recommendations. We ask what can be learned from online discussions among people who dispute and distrust the official recommendations.

Main points: A growing share of the population no longer trusts the dietary advice offered by private and government health agencies. They believe the supposed benefits of the low-fat, grain-based diets promoted by those agencies are not based on solid science and that benefits of low-carbohydrate diets have been deliberately squelched. The following is typical of comments the authors (whose websites draw a combined 1.5 million visitors monthly) receive daily:

“The medical and pharmaceutical companies have no interest in us becoming healthy through nutrition. It is in their financial interest to keep us where we are so they can sell us medications.”

Similar distrust of the government’s dietary recommendations has been expressed by doctors and academics. The following comments, left by a physician on one of the authors’ blogs, are not unusual:

“You and Denise Minger should collaborate on a book about the shoddy analysis put out by hacks like the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee.”

“Sometimes I wonder if people making these statements even took a basic course in biochemistry and physiology.”

Many patients have given up on their health care professionals and turn to Internet sites for advice they trust. This is particularly true of diabetics who find that a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet is not helping them control their blood glucose. As one woman wrote about her experience with a diabetes center:

“I was so frustrated, I quit going to the center for check ups.”

The data suggest a serious problem in science-community interactions which needs to be explored.

Conclusions & recommendations: Our findings document a large number of such cases pointing to the need for public hearings and or conference. The community is not well served by an establishment that refuses to address its critics from within the general population as well as health professionals.

Who says you cannot speak of reason to the Dane and lose your voice? Who says two wrongs don’t make a right?

Posted: October 11, 2011 in Association and Causality, Evidence Based Medicine, low-carbohydrate diet, Tax on FatTags: biochemistry, carbohydrate, dietary guidelines

The King in Hamlet says “you cannot speak of reason to the Dane and lose your voice” and most Americans do feel good about the Danes. We hold to the stereotype that they are friendly folk with a dry sense of humor like Victor Borge. That is why Reuben and Rose Mattus, the Polish-Jewish immigrant ice-cream makers from the Bronx who tried to find an angle that would allow them to compete with Sealtest® and other big guns, picked Häagen-Dazs® as the name for their up-scale ice cream, even including a map of Denmark on the early packaging. (Never mind that there is no Scandinavian language that has the odd-ball collection of foreign-looking spelling; Danish does not have an umlaut and I don’t think any Indo-European language has the combination “zs;” there is Zsa Zsa Gabor, of course, but Hungarian is a Uralic language related only to languages that you never heard of).

The original post here held that the Mattuses would have been very surprised to see that products like their high-butterfat ice cream are now a target of the Danish government which instituted a tax on foods containing saturated fat on October 1 of 2011. The tax, I am happy to say has since been repealed. In a brilliant turn-around that gives a great insight into the mind of the tax man, the Times reported that ” the tax raised $216 million in new revenue. To offset the loss of that money, the Legislature plans a small increase in income taxes and the elimination of some deductions.” Get it? They are going to increase taxes to cover the money that they hoped to have, never mind, that the intention was to stop people from buying the stuff that would bring in the revenue.

The original idea for collecting taxes on a number of items including “sugar, fat and tobacco,” came from Jakob Axel Nielsen (right), then Sundhedsminister. A graduate of the law school at Aarhus, Nielsen is reputed to know even more about science than Hizzona’ Michael Bloomberg. The LA Times points out, however, that “for those who may be tempted to call for Nielsen’s job, please note that he stepped down…last year.”

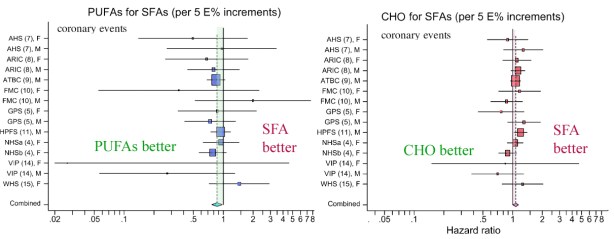

One of the things that is surprising about all this is that, in 2009, a combined Danish and American research group whose senior author was Dr. Marianne Jakobsen of Copenhagen University Hospital published a paper showing that there was virtually no effect of dietary saturated fatty acids (SFAs) on cardiovascular disease. The study was a meta-analysis which means a re-evaluation of many previous studies. The authors concluded that the results “suggest that replacing SFA intake with PUFA (polyunsaturated fatty acid) intake rather than MUFA (monounsaturated fatty acids) or carbohydrate intake prevents CHD (coronary heart disease) over a wide range of intakes.”

As in many nutritional papers, it is worthwhile to actually look at the data. The figure below, from Jakobsen’s paper shows the results from several studies in which the effect of substituting 5 % of energy from SFA with either carbohydrate (CHO) or PUFA or MUFA (not shown here) was measured. The outcome variable is the hazard ratio for incidence of coronary events (heart attack, sudden death). You can think of the hazard ratio as similar to an odds ratio which is what it sounds like: the comparative odds of different possible outcomes. The basic idea is that if 10 people in a group of 100 have a heart attack with saturated fat in their diet, the odds = 10 out of 100 or 1/10. If you now replace 5 % of energy with PUFAs for a different group of 100 and find only 8 people have an event, then the odds for the second group is 8/100 and the odds ratio is 0.8 (8/100 divided by 10/100). If the odds ratio were 1.0, then there would be no benefit either way, no difference if you keep SFAs or replace. So in the first figure below, most of the points are to the left of the point 1.0, suggesting that PUFA is better than SFA but the figure on the right suggests that SFA is better than CHO. But is this real?

You probably noticed that you would have the same odds ratio if the sample sizes were 1000. In other words, a ratio gives relative values and obscures some information. If there were a large number of people and the real numbers were actually 8 and 10, you wouldn’t put much stock in the hazard ratio; decreasing your chances of a low probability event is not a big deal; you double your chances of winning the lottery by buying two tickets. In fact, whereas heart disease is a big killer, if you study a thousand people for 5 years there will be only a small number of coronary events. I discussed this in a previous post, but giving Jakobsen the benefit of the doubt that there were really differences on outcomes, we need to know whether the hazard ratios are really reliable. In this case, Jakobsen showed the variability in the results with “95% confidence intervals,” which are represented by the horizontal bars in the figure.

The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) is a measure of the spread of values around the average. It tells you how reliable the data is. Technically, the term means that if you calculate the size of the interval over and over, 95% of the time the interval will contain the true value. Although not technically precise, you could think of it as meaning that there is a 95% chance of the interval containing the true value.

There is one important point here. It is a statistical rule that if the 95% CI bar crosses the line for hazard ratio = 1.0 then this is taken as indiction that there is no significant difference between the two conditions, in this case, SFAs or a replacement. Looking at the figure from Jakobsen, we are struck by the fact that, in the list of 15 different studies for two replacements, all but one cross the hazard ratio = 1.0 line; one study found that keeping SFAs in the diet provides a lower risk than replacement with carbohydrate. For all the others it was a wash. At this point, one has to ask why a combined value was calculated. How could 15 studies that show nothing add up to a new piece of information. Who says two wrongs, or even 15, can’t make a right? The remarkable thing is that some of the studies in this meta-analysis are more than 20 years old. How could these have had so little impact? Why did we keep believing that saturated fat was bad?

Taxing Saturated Fat.

Now the main thing that taxes do is bring in money. That’s why it is not a good idea to tie it to a health strategy unless you are really sure (as in the case of cigarettes). For one thing, there is something contradictory (or pessimistic) about trying to raise money from a behavior that you want people to stop doing. In any case, given that during the epidemic of obesity and diabetes, saturated fat intake went down (for men, the absolute amount went down by 14%), and that there was no effect on the incidence of heart disease (although survival was better due to treatment), there is every reason to consider the possibility of unexpected negative outcomes (think margarine and trans-fat). Although now repealed, it is worth considering possible unintended consequences (since the sugar tax is still alive). Suppose that the Danes had reduced consumption of saturated fat but still ate enough to bring in money. And suppose that this had the opposite effect — after all, if you believe the Jakobsen study, substituting carbohydrate for saturated fat will increase cardiovascular risk. So now there would be a revenue stream that was associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease. What would they have done? What would we do? Well, we’d stop it, of course. Yeah, right.