“In the Viking era, they were already using skis…and over the centuries, the Norwegians have proved themselves good at little else.”

–John Cleese, Norway, Home of Giants.

With the 3-foot bookshelf of popular attacks on the low-fat-diet-heart idea it is pretty remarkable that there is only one defense. Daniel Steinberg’s Cholesterol Wars. The Skeptics vs. The Preponderance of Evidence is probably more accurately called a witness for the prosecution since low-fat, in some way or other is still the law of the land.

The Skeptics vs. the Preponderance of Evidence

The book is very informative, if biased, and it provides an historical perspective describing the difficulty of establishing the cholesterol hypothesis. Oddly, though, it still appears to be very defensive for a witness for the prosecution. In any case, Steinberg introduces into evidence the Oslo Diet-Heart Study [2] with a serious complaint:

“Here was a carefully conducted study reported in 1966 with a statistically significant reduction in reinfarction [recurrence of heart attack] rate. Why did it not receive the attention it deserved?”

“The key element,” he says, “was a sharp reduction in saturated fat and cholesterol intake and an increase in polyunsaturated fat intake. In fact. each experimental subject had to consume a pint of soybean oil every week, adding it to salad dressing or using it in cooking or, if necessary, just gulping it down!”

Whatever it deserved, the Oslo Diet-Heart Study did receive a good deal of attention. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), liked it. The WHI was the most expensive failure to date. It found that “over a mean of 8.1 years, a dietary intervention that reduced total fat intake and increased intakes of vegetables, fruits, and grains did not significantly reduce the risk of CHD, stroke, or CVD in postmenopausal women.” [3]

The WHI, adopted a “win a few, lose a few” attitude, comparing its results to the literature, where some studies showed an effect of reducing dietary fat and some did not — this made me wonder: if the case is so clear, whey are there any failures. Anyway, it cited the Oslo Diet-Heart Study as one of the winners and attributed the outcome to the substantial lowering of plasma cholesterol.

So, “cross-examination” would tell us why, if “a statistically significant reduction in reinfarction rate” it did “not receive the attention it deserved?”

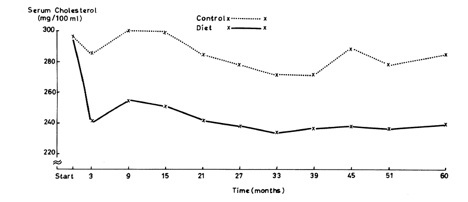

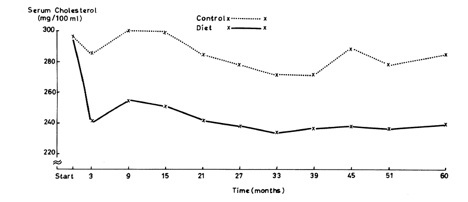

First, the effect of diet on cholesterol over five years:

The results look good although, since all the numbers are considered fairly high, and since the range of values is not shown, it is hard to tell just how impressive the results really are. But we will stipulate that you can lower cholesterol on a low-fat diet. But what about the payoff? What about the outcomes?

The results are shown in Table 5 of the original paper: Steinberg described how in the first 5 years: “58 patients of the 206 in the control group (28%) had a second heart attack” (first 3 lines under first line of blue-highlighting) but only

“… 32 of the 206 in the diet (16%)…” which does sound pretty good.

In the end, though, it’s really the total deaths from cardiac disease. The second blue-highlighted line in Table 5 shows the two final outcome. How should we compare these.

1. The odds ratio or relative risk is just the ratio of the two outcomes (since there are the same number of subjects) = CHD mortality (diet)/ CHD mortality control) = 94/79 = 1.19. This seems strikingly close to 1.0, that is, flip of a coin. These days the media, or the report itself, would report that there was a 19 % reduction in total CHD mortality.

2, If you look at the absolute values, however, the mortality in the controls is 94/206 = 45.6 % but the diet group had reduced this to 79/206 = 38.3 % so the change in absolute risk is 45.6 % – 38.3 % or only 7.3 % which is less impressive but still not too bad.

3. So for every 206 people, we save 94-79 = 15 lives, or dividing 206/15 = 14 people needed to treat to save one life. (Usually abbreviated NNT). That doesn’t sound too bad. Not penicillin but could be beneficial. I think…

Smoke and mirrors.

It’s what comes next that is so distressing. Table 10 pools the two groups, the diet and the control group and now compares the effect of smoking: on the whole population, the ratio of CHD deaths in smokers vs non-smokers is 119/54 = 2.2 (magenta highlight) which is somewhat more impressive than the 1.19 effect we just saw. Now,

1. The absolute difference in risk is (119-54)/206 = 31.6 % which sounds like a meaningful number.

2. The number needed to treat is 206/64 = 3.17 or only about 3 people need to quit smoking to see one less death

In fact, in some sense, the Oslo Diet-Heart Study provides smoking-CHD risk as an example of a meaningful association that one can take seriously. If only such a significant change had actually been found for the diet effect.

So what do the authors make of this? Their conclusion is that “When combining data from both groups, a three-fold greater CHD mortality rate is demonstrable among the hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive smokers than among those in whom these factors were low or absent.” Clever but sneaky. The “hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive” part is irrelevant since you combined the groups. In other words, what started out as a diet study has become a “lifestyle study.” They might has well have said “When combining data from fish and birds a significant number of wings were evident.” Members of the jury are shaking their heads.

Logistic regression. What is it? Can it help?

So they have mixed up smoking and diet. Isn’t there a way to tell which was more important? Well, of course, there are several ways. By coincidence, while I was writing this post, April Smith posted on facebook, the following challenge “The first person to explain logistic regression to me wins admission to SUNY Downstate Medical School!” I won although I am already at Downstate. Logistic regression is, in fact, a statistical method that asks what the relative contribution of different inputs would have to be to fit the outcome and this could have been done but in this case, I would use my favorite statistical method, the Eyeball Test. Looking at the data in Tables 5 and 10 for CHD deaths, you can see immediately what’s going on. Smoking is a bigger risk than diet.

If you really want a number, we calculated relative risk above. Again, we found for mortality, CHD (diet)/ CHD (control) = 94/79 = 1.19. But what happens if you took up smoking: Figure 10 shows that your chance of dying of heart disease would be increased by 119/54 = 2.2 or more than twice the risk. Bottom line: you decided to add saturated fat to your diet, your risk would be 1.19 what it was before which might be a chance you could take faced with authentic Foie Gras.

Daniel Steinberg’s question:

“Here was a carefully conducted study reported in 1966 with a statistically significant reduction in reinfarction rate. Why did it not receive the attention it deserved?”

Well, it did. This is not the first critique. Uffe Ravnskov described how the confusion of smoking and diet led to a new Oslo Trial which reductions in both were specifically recommended and, again, outcomes made diet look bad [4]. Ravnskov gave it the attention it deserved. But what about researchers writing in the scientific literature. Why do they not give the study the attention it deserves. Why do they not point out its status as a classic case of a saturated fat risk study with no null hypothesis. It certainly deserves attention for its devious style. Of course, putting that in print would guarantee that your grant is never funded and your papers will be hard to publish. So, why do researchers not give the Oslo-Diet-Heart study the attention it deserves? Good question, Dan.

Bibliography

1. Steinberg D: The cholesterol wars : the skeptics vs. the preponderance of evidence, 1st edn. San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press; 2007.

2. Leren P: The Oslo diet-heart study. Eleven-year report. Circulation 1970, 42(5):935-942.

3. Howard BV, Van Horn L, Hsia J, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kuller LH, LaCroix AZ, Langer RD, Lasser NL et al: Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. JAMA 2006, 295(6):655-666.

4. Ravnskov U: The Cholesterol Myths: Exposing the Fallacy that Cholesterol and Saturated Fat Cause Heart Disease. Washington, DC: NewTrends Publishing, Inc.; 2000.