Following the government’s nutritional advice can make you fat and sick.

by STEVEN MALANGA

City Journal, May 10, 2011

Last October, embarrassing e-mails leaked from New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene disclosed that officials had stretched the limits of credible science in approving a 2009 antiobesity ad, which depicted a stream of soda pop transforming into human fat as it left the bottle. “The idea of a sugary drink becoming fat is absurd,” a scientific advisor warned the department in one of the e-mails, a view echoed by other experts whom the city consulted. Nevertheless, Gotham’s health commissioner, Thomas Farley, saw the ad as an effective way to scare people into losing weight, whatever its scientific inaccuracies, and overruled the experts. The dustup, observed the New York Times, “underlined complaints that Dr. Farley’s more lifestyle-oriented crusades are based on common-sense bromides that may not withstand strict scientific scrutiny.”

Under Farley and Mayor Michael Bloomberg, New York’s health department has been notoriously aggressive in pursuing such “lifestyle-oriented” campaigns (see the sidebar below). But America’s public-health officials have long been eager to issue nutrition advice ungrounded in science, and nowhere has this practice been more troubling than in the federal government’s dietary guidelines, first issued by a congressional committee in 1977 and updated every five years since 1980 by the United States Department of Agriculture. Controversial from the outset for sweeping aside conflicting research, the guidelines have come under increasing attack for being ineffective or even harmful, possibly contributing to a national obesity problem. Unabashed, public-health advocates have pushed ahead with contested new recommendations, leading some of our foremost medical experts to ask whether government should get out of the business of telling Americans what to eat—or, at the very least, adhere to higher standards of evidence.

Until the second half of the twentieth century, public medicine, which concerns itself with community-wide health prescriptions, largely focused on the germs that cause infectious diseases. Advances in microbiology led to the development of vaccines and antibiotics that controlled—and, in some cases, eliminated—a host of killers, including smallpox, diphtheria, and polio. These advances dramatically increased life expectancy in industrialized countries. In the United States, average life expectancy improved from 49 years at the beginning of the twentieth century to nearly 77 by the century’s end.

As the threat of communicable diseases receded, public medicine began to turn its attention to treating and preventing health problems that weren’t germ-caused, such as chronic heart disease and strokes, the death rates for which seemed to be soaring after World War II. Some observers cautioned that the apparent increase might be the result of diagnostic advances, which had improved doctors’ ability to detect heart ailments. This possibility, however, failed to deter the press and advocacy groups like the American Heart Association from declaring the arrival of a frightening epidemic.

One theory blamed the problem on the American diet, and in particular on cholesterol—both the kind that you ingest when you eat animal products and the kind that your body produces when you eat saturated fats. It wasn’t an unreasonable idea; cholesterol is, after all, one component of the plaque that clogs arteries and causes heart attacks and strokes. But isolating the true causes of coronary disease proved elusive. Multiple factors—not just diet but other personal habits, such as smoking, and genetics as well—were potential contributors. And measuring the influence of diet was especially difficult because of big variations among individuals in everything from blood composition to their response to different foods. Numerous studies on diet proved so inconclusive that in 1969, the National Institutes of Health found no hard evidence that what people ate had a significant impact on heart disease.

Nevertheless, in the 1970s, Democratic senator George McGovern’s Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs decided to fight the apparent epidemic by making recommendations on nutrition. “Our diets have changed radically within the past 50 years,” McGovern declared, “with great and very often harmful effects on our health.” As science writer Gary Taubes notes in Good Calories, Bad Calories, the McGovern committee, in coming up with its diet plan, had to choose among very different nutritional regimes that scientists and doctors were studying as potentially beneficial to those at risk for heart disease. Settling on the unproven theory that cholesterol was behind heart disease, the committee issued its guidelines in 1977, urging Americans to reduce the fat that they consumed from 40 percent to 30 percent of their daily calories, principally by eating less meat and fewer dairy products. The committee also advised raising carbohydrate intake to 60 percent of one’s calories and slashing one’s intake of cholesterol by a quarter.

Some of the country’s leading researchers spoke out against the guidelines and against population-wide dietary recommendations in general. Edward Ahrens, an expert in the chemistry of fatty substances at Rockefeller University, characterized the guidelines as “simplistic and a promoter of false hopes” and complained that they treated the population as “a homogenous group of [laboratory] rats while ignoring the wide variation” in individual diet and blood chemistry. The Food and Nutrition Board of the National Academy of Sciences released its own dietary suggestions, which saw “no reason for the average healthy American to restrict consumption of cholesterol, or reduce fat intake,” and just encouraged people to keep their weight within a normal range.

Even members of McGovern’s committee demurred. In a supplemental foreword to the second edition of the guidelines, ranking Republican senator Charles Percy acknowledged that the scientific record included “extreme diversity of opinion.” Canada’s Department of National Health and Welfare, Percy noted, had recently declared that “evidence is mounting that dietary cholesterol may not be important to the great majority of people”; Great Britain’s Department of Health and Social Security had reached a similar conclusion in 1974. Percy concluded that it was important to inform the public “not only about what is known, but what is controversial.”

Still, the low-fat guidelines gained traction in an era when food advocacy and vegetarianism were rising, as Taubes relates. In 1968, Paul Ehrlich had published his apocalyptic bestseller, The Population Bomb, prophesying mass starvation because the earth could no longer provide enough food for humanity. Ehrlich’s book was out of date as soon as it appeared, thanks to scientific advances that made agriculture more productive worldwide. But it nevertheless gave ammunition to advocates who urged people in developed countries to eat fewer animal products so that the world’s poor, supposedly hungrier and hungrier, could consume more of the grain that wealthy nations turned into feed for domestic animals. In 1971, Frances Moore Lappé’s vegetarian manifesto Diet for a Small Planet hit the bestseller list.

A new kind of health-care advocate, evincing a passion far removed from disinterested scientific inquiry, also took up the campaign for a vegetable-based, low-fat diet. A good example was the Center for Science in the Public Interest, which in 1975 organized a National Food Day that included, the New York Times reported, an “all-out attack” on foods that it considered harmful. On the hit list: prime beef, high in fat and cholesterol.

When the McGovern committee issued its guidelines, these advocacy groups attacked opponents as shills for the food industry—dismissing the National Research Council’s more restrained dietary recommendations, for instance, because some of the scientists who worked on them also served as consultants to industry groups like the Egg Council. By contrast, the advocates noted, the McGovern guidelines were largely the work of a committee staffer, a former newspaper reporter whose very lack of scientific expertise meant that he had no such conflicts.

But the line between advocate and policymaker was blurring on both sides of the debate. One of the important figures promoting the dietary guidelines was Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Carol Foreman, who had formerly been director of the Consumer Federation of America, a cosponsoring organization of National Food Day. “People were getting sick and dying because we ate too much,” she told Taubes. She urged government scientists to tell Americans what to eat, even if “it’s not the final answer.”

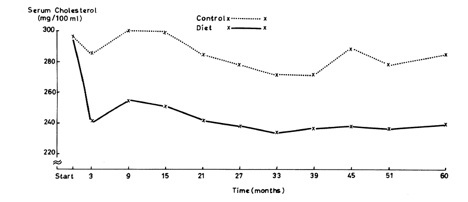

The McGovern dietary recommendations weren’t just ahead of the science, though; they were racing ahead of it. Two of the most important U.S. government–sponsored studies on the role of fat and cholesterol in heart disease didn’t appear until the early 1980s, long after the committee had promulgated its advice. The results hardly cleared things up. The first study, known as the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial, followed 12,866 people between the ages of 35 and 57 at risk for heart disease. Some of these subjects were placed on a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet; others were merely told to keep seeing the family doctor. The study found no statistically significant difference in mortality rates between the two groups.

The results of the second study, the Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial, appeared in 1984 and continue to spark debate. Using the drug cholestyramine to reduce high cholesterol rates in a group of male test subjects, the study reported a lower death rate for those on the drug than for subjects who took a placebo. Did this mean that cholesterol was to blame for heart disease, after all? Some observers, including Ahrens, cautioned that the average cholesterol level of the American public was far lower than that of the test group taking cholestyramine, meaning that there was nothing in the study to suggest that a nationwide effort to change citizens’ diets would make much difference in public health. But the press seemed to prefer a narrative that made diet a major cause of heart attacks. A 1984 Time cover story about cholesterol showed a dinner plate turned into an unhappy face, with two sunny-side-up eggs the frazzled-looking eyes above a frowning strip of bacon.

The scientific controversy grew more intense. In 1992, an authoritative review of 19 cholesterol studies worldwide found that, while men with cholesterol levels above 240 were disproportionately likely to suffer heart attacks, men with cholesterol levels below 160 were disproportionately likely to die from all causes, including lung cancer, respiratory disease, and digestive disease—an outcome that suggested a relationship between lowcholesterol levels and disease, something that scientists had never considered. The study also showed no difference in mortality rates for men with cholesterol levels between 160 and 240, even though the guidelines advised keeping levels below 200. Perhaps most surprisingly, the study also found that cholesterol levels made no difference at all in death rates among women. There was little doubt that some public-health researchers wished such research would go away. “Some people don’t want to talk about it,” said Michael Criqui, an epidemiologist at the University of California at San Diego and an associate editor of Circulation, which published the review. “They think it is going to impede public-health measures.”

More recent research has further undermined the cholesterol-as-bad-guy hypothesis. Scientific American summed up the disturbing state of the evidence in April 2010. The magazine cited a meta-analysis—that is, a combination of data from several large studies—of the dietary habits of 350,000 people worldwide, published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, which found no association between the consumption of saturated fats and heart disease. Another recent study noted by Scientific American, by Harvard nutrition and epidemiology professor Meir Stampfer and associates and published in The New England Journal of Medicine, tracked 322 moderately obese people, each following one of three diets: a low-fat, calorie-restricted diet of the sort that the American Heart Association recommends; a so-called Mediterranean diet, rich in vegetables and low in red meat; and a low-carbohydrate diet without any calorie restrictions. Not only did the low-carb dieters lose the most weight, the study found; they also had the healthiest ratio of HDL (so-called good) cholesterol to LDL (bad) cholesterol.

The latest nutritional thinking has indeed zeroed in on carbohydrates as a likely cause of heart disease. Easily digestible carbs, in particular—starches like potatoes, white rice, and bread from processed flour, as well as refined sugar—make it hard to burn fat and also increase inflammations that can cause heart attacks, several studies have concluded. A 2007 Dutch study of 15,000 women found that those who ate foods with the highest “glycemic load,” a measure of portion sizes and of how easily digestible a food is, had the greatest risk of heart disease.

Looking at such evidence, several top medical scientists have concluded that the government’s carb-heavy guidelines may actually have harmed public health. In 2008, three researchers from the Albert Einstein School of Medicine—including the associate dean of clinical research, Paul Marantz, and a former president of the International Hypertension Society, Michael Alderman—observed in The American Journal of Preventive Medicine that since 1977, Americans have largely followed the government’s advice, doubtless as conveyed by the doctors they consulted. Men, for instance, cut their fat intake from 37 percent of their daily calories to 32 percent and increased their carbohydrate intake from 42 percent to 49 percent. Yet over the same three decades, the fraction of American men who were overweight or obese increased from 53 percent of the population to about 69 percent. The doctors wondered whether this correlation was an unintended consequence of telling the entire population to change its eating patterns. “In general,” the doctors wrote, “weak evidentiary support has been accepted as adequate justification for [the U.S. dietary] guidelines. This low standard of evidence is based on several misconceptions, most importantly the belief that such guidelines could not cause harm.” But, they concluded, “it now seems that the U.S. dietary guidelines recommending fat restriction might have worsened rather than helped the obesity epidemic and, by so doing, possibly laid the groundwork for a future increase in CVD,” cardiovascular disease.

It’s true that the particular kind of carbohydrates that the government has always recommended are carbs rich in fiber, which aren’t as quickly digested as those starches implicated by the latest research. But it’s difficult to tell an entire population to change its dietary habits without sowing confusion about such fine points. Further, as an October 2010 article in Nutrition points out, the government’s definition of what constitutes a fiber-rich grain is so broad as to include many foods that might actually promote heart disease because they are too easily digestible. “At a minimum,” says one of the authors of the Nutrition piece, SUNY Downstate Medical Center biologist Richard Feinman, “if you have an area of controversy or ambiguity in the science, you shouldn’t be issuing guidelines to the entire population.”

The guidelines themselves quietly acknowledge that they may have worsened public health. The 2000 version eliminated the recommendation to reduce intake of overall fat in favor of carbs, noting “the possibility that overconsumption of carbohydrates may contribute to obesity.” But that was as far as the government would go. It retained the advice to limit consumption of saturated fat and to keep intake of cholesterol to 300 milligrams per day, for example, even though dietary cholesterol—that is, the cholesterol we ingest by eating animal products—has been discounted by many researchers as a source of plaque buildup. (It was this advice about dietary cholesterol that led doctors, starting in the 1970s, to counsel patients to avoid eggs. Subsequent studies have concluded that any restrictions on eating them are “unwarranted for the majority of people and are not supported by scientific data,” as a 2004 article in The Journal of Nutrition put it.)

Supporters of the guidelines have increasingly resorted to ad hoc, even political, justifications for them. In a 2008 American Journal of Preventive Medicine article, for example, two influential nutritionists, Marion Nestle of New York University and Steven Woolf of the Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center, admit that “whether the evidence is good enough to recommend population-based dietary changes comes down to a matter of subjective judgment.” But developing dietary recommendations is still a crucial government responsibility, they argue, in part because the government is already heavily involved in food policies. “Dietary guidelines have implications at every level of government, from federal agencies such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to the local school board,” they write, and without clear guidelines, big food industries and special interests could lobby political leaders and shape policy in unhealthy ways. But this argument makes sense only if you assume that the government’s guidelines will be any healthier.

Nestle and Woolf also argue that government’s success in persuading people to stop smoking justifies its efforts to change American eating habits. “If it was paternalistic for the government to advise people how to eat,” they ask rhetorically, “was it equally paternalistic . . . to alert the public about the hazards of tobacco use and to recommend in 1964 that smokers give up cigarette smoking?” But the major scientific dissenters from government dietary policy don’t accuse it of paternalism, though that’s a legitimate argument; they dissent because they find the government’s evidence inadequate and its recommendations potentially harmful.

The government’s response to the growing controversy has been to keep issuing the guidelines—and call for more research. Asked last year about whether the 2010 update would reflect the latest studies challenging previous recommendations, a USDA spokesperson merely suggested that the controversial areas be “put on the list of things to do with regard to more research.” In other words, more research is needed to overturn or withdraw the current recommendations, even though they were based on inconclusive evidence from the start.

Mike Bloomberg, Food Cop

In his 2005 book Prescription for a Healthy Nation, Dr. Thomas Farley wondered why “Americans behave in such an unhealthy way” and concluded that we don’t have the will to overcome the temptations around us, like easy access to junk food. Publishers Weekly noted that the book had “a pervasive tone of puritanical disapproval” and that Farley and his coauthor, Dr. Deborah Cohen, sounded like a “pair of scolds.” In 2008, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg made the first of the scolds the city’s health commissioner, and Farley hasn’t disappointed. He’s carried on a tradition—begun by Bloomberg and his first health commissioner, Thomas Frieden, now director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—of pursuing population-wide dietary policies that are aggressive, questionable, and born from the belief that government should regulate Americans’ indulgent behavior.

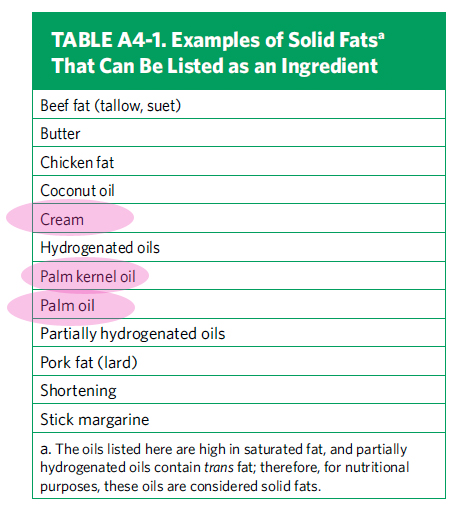

Early in his tenure, Frieden had his hands full, confronting everything from a SARS scare to a drug-resistant form of HIV. He nonetheless expanded his portfolio beyond these classic public-health threats into the more controversial area of lifestyle recommendations. In 2005, he began a campaign against man-made trans fats of the sort that appear in partially hydrogenated oils, which ultimately led to a ban on them—the first of its kind—in the city’s restaurants. Then the city mandated that chain restaurants include calorie counts in their menus. In 2009, Frieden and then Farley began a nationwide campaign to get food companies to use less sodium. Most recently, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has waged a campaign against sugared soda pop, aggressively linking it to human fat in a cause-and-effect relationship that even the city’s own scientific advisors have rejected.

Bloomberg’s interest in the field predates his mayoralty; the nation’s largest school of public-health medicine, at Johns Hopkins University, is named after him in gratitude for his large donations. But the health campaigns that he has run from city hall have made him a national influence. The Harvard School of Public Health Medicine awarded him its top honor in 2007. The 2009 federal health-care legislation commonly known as Obamacare, following New York’s lead, will require chain restaurants nationwide to post calorie counts, while the dietary guidelines issued by the United States Department of Agriculture, picking up where New York left off, are now targeting sodium as a health risk, too.

Among scientists, however, the Bloomberg administration’s crusades are controversial, because they push the limits of what research has shown and ignore the potential unintended consequences of advising entire populations on how to change their diets. In an article titled “The Panic Du Jour: Trans Fats,” New York Times nutrition columnist Gina Kolata noted that studies show trans fats to be no more dangerous than saturated fats. The authors of a 2008 article in The American Journal of Preventive Medicine, “A Call for Higher Standards of Evidence for Dietary Guidelines,” worried that “the net of effects of legal restrictions” on trans fats was unknown and that a ban could backfire if it led Americans to assume that foods without trans fats were healthful. Meanwhile, a study by researchers at New York University of the city’s calorie-posting law found that it had no effect on what consumers bought. Though a quarter of parents in the study claimed to consult the calorie postings before buying food for their kids, their receipts showed no calorie difference between the meals that they’d purchased and those purchased by parents who didn’t look at the postings.

Apparently, none of these controversies gave the Bloomberg administration pause. The city undertook its 2009 campaign against salt despite decades of scientific uncertainty about whether lowering sodium consumption matters to anyone except those few Americans highly sensitive to salt.

The mayor and his health commissioners have exaggerated the potential health benefits of their campaigns, in the process raising fundamental questions about the point at which a government should intervene in public-health matters. Bloomberg himself estimated, for instance, that the trans-fat ban would save “a couple of hundred lives a year in New York City,” a completely untested statement that failed to take into account a host of possibilities—for example, that people might start to consume an alternative to trans fats that would do just as much harm. But such exaggerations are increasingly common in public-health medicine because overstating the beneficial effects of policies helps get them enacted.

As if all this weren’t troubling enough, the USDA, again with uncertain scientific warrant, is now targeting sodium as a public-health menace. Following the lead of New York City’s health department, which is prodding food manufacturers to make their products less salty, the 2010 guidelines recommend that sodium consumption fall as low as 1,500 milligrams a day for those over 51, more than a one-third reduction from the amount that the previous version of the guidelines suggested.

For the general population of healthy Americans, however, that advice may be pointless or, again, even harmful. Decades of research have yielded continuing controversy over the benefits of lowering salt consumption. The science remains so inconclusive that Alderman recently described calls to reduce sodium intake as merely “opinion or common practice,” not science. Experts like the authors of the October 2010 Nutrition article argue that people with particular health problems, such as hypertension, may indeed suffer from excessive sodium intake. But that’s a far cry from saying that everybody should cut down on salt. Alderman, an expert on hypertension, worries that the war on salt may have unintended consequences; diets that reduce salt intake produce a host of physiological changes, including decreased insulin sensitivity, which can raise the risk of heart disease. None of these concerns has stopped the Center for Science in the Public Interest from waging a zealous public-health crusade denouncing salt as “the deadly white powder you already snort.”

It’s all the more important to understand the problems with the dietary guidelines as the federal government embarks on its new campaign against obesity, which research and clinical experience have shown to be a major factor in ailments like diabetes and chronic heart disease. When the White House announced late last year that First Lady Michelle Obama would lead the fight against childhood obesity and she observed that “we can’t just leave it up to parents,” some prominent conservatives, including columnist Michelle Malkin and former vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin, accused the administration of entering an arena where parents, not the government, should be making decisions.

Opponents of the administration’s plans, however, shouldn’t just debate the government’s proper role in people’s health; they should also point out that its population-wide diet advice goes well beyond what science has established. “Some people in this field act more like zealots with a passion for a cause than scientists waiting for the evidence to support their conclusions,” complains California Polytechnic public-health economist Michael Marlow. As Marlow notes, America’s obesity rate was far lower back when nutrition was largely a parental responsibility, before government became widely involved in the diet-advice business.

The best thing government can encourage Americans to do on the health front may well be to develop their own diet and exercise programs, based on their individual circumstances, in consultation with health-care professionals. Otherwise, public-health medicine risks violating the central principle of medical ethics: First, do no harm.

Steven Malanga is the senior editor of City Journal and a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute. He is the author of Shakedown: The Continuing Conspiracy Against the American Taxpayer.

City Journal offers a stimulating mix of hard-headed practicality and cutting-edge theory, with articles on everything from school financing, policing strategy, and welfare policy to urban architecture, family policy, and the latest theorizing emanating from the law schools, the charitable foundations, even the schools of public health. Since urban policy encompasses almost all domestic policy questions, as well as the largest issues of our culture and society, the magazine views its canvas as very broad indeed. The magazine holds itself to the highest intellectual, journalistic, and literary standards, aiming to produce intelligent and absorbing reading for intelligent and discerning readers.

Journal Nutrition Article: In the face of contradictory evidence: Report of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans Committee