Baseball is like church. Many attend. Few understand.

— Leo Durocher.

The movie Moneyball provides an affirmative answer to an important question in literature and drama: can you present a scene and bring out the character of a subject that is boring while, at the same time, not make the presentation boring? The movie, and Michael Lewis’sbook that it is based on, are about baseball and statistics! For fans, baseball is not boring so much as incredibly slow, providing a soothing effect like fishing, interspersed with an occasional big catch. The movie stars Brad Pitt as Billy Beane, the General Manager of the Oakland Athletics baseball team in the 1990s. A remarkably talented high school athlete, Billy Beane, for unknown reasons, was never able to play out his potential as an MLB player but, in the end, he had a decisive effect on the game at the managerial level. The question is how the A’s, with one-third of the budget of the Yankees, could have been in the play-offs three years in a row and, in 2001, could win 102 games. The movie is more or less faithful to the book and both are as much about organizations and psychology as about sports. The story was “an example of how an unscientific culture responds, or fails to respond, to the scientific method” and the science is substantially statistical.

In America, baseball is a metaphor for just about everything. Probably because it is an experience of childhood and adolescence, lessons learned from baseball stay with us. Baby-boomers who grew up in Brooklyn were taught by Bobby Thompson’s 1951 home-run, as by nothing later, that life isn’t fair. The talking heads in Ken Burns’s Baseball who found profound meaning in the sport are good examples. Former New York Governor Mario Cuomo’s comments were quite philosophical although he did add the observation that getting hit in the head with a pitched ball led him to go into politics.

One aspect of baseball that is surprising, especially when you consider the money involved, is the extent to which strategy and scouting practices have generally ignored hard scientific data in favor of tradition and lore. Moneyball tells us about group think, self-deception and adherence to habit in the face of science. For those of us who a trying to make sense of the field of nutrition, where people’s lives are at stake and where numerous professionals who must know better insist on dogma — low fat, no red meat — in the face of contradictory evidence, baseball provides some excellent analogies.

The real stars of the story are the statistics and the computer or, more precisely, the statistics and computer guys: Bill James an amateur analyzer of baseball statistics and Paul DePodesta, assistant General Manager of the A’s who provided information about the real nature of the game and how to use this information. James self-published a photocopied book called 1977 baseball abstract: featuring 18 categories of statistical information you just can’t find anywhere else. The book was not just about statistics but was in fact a critique of traditional statistics pointing out, for example, that the concept of an “error;” was antiquated, deriving from the early days of gloveless fielders and un-groomed playing fields of the 1850s. In modern baseball, “you have to do something right to get an error; even if the ball is hit right at you, and you were standing in the right place to begin with.” Evolving rapidly, the Abstracts became a fixture of baseball life and are currently the premium (and expensive) way to obtain baseball information.

It is the emphasis on statistics that made people doubt that Moneyball could be made into a movie and is probably why they stopped shooting the first time around a couple of years ago. Also, although Paul DePodesta (above) is handsome and athletic, Hollywood felt that they should cast him as an overweight geek type played by Jonah Hill. All of the characters in the film have the names of the real people except for DePodesta “for legal reasons,” he says. Paul must have no sense of humor.

The important analogy with nutrition research and the continuing thread in this blog, is that it is about the real meaning of statistics. Lewis recognized that the thing that James thought was wrong with the statistics was that they

“made sense only as numbers, not as a language. Language, not numbers, is what interested him. Words, and the meaning they were designed to convey. ‘When the numbers acquire the significance of language,’ he later wrote, ‘they acquire the power to do all the things which language can do: to become fiction and drama and poetry … . And it is not just baseball that these numbers through a fractured mirror, describe. It is character. It is psychology, it is history, it is power and it is grace, glory, consistency….’”

By analogy, it is the tedious comparison of quintiles from the Harvard School of Public Health proving that white rice will give you diabetes but brown rice won’t or red meat is bad but white meat is not, odds ratio = 1.32. It is the bloodless, mindless idea that if the computer says so, it must be true, regardless of what common sense tells you. What Bill James and Paul DePodesta brought to the problem was understanding that the computer will only give you a meaningful answer if you ask the right question; asking what behaviors accumulated runs and won ball games, not which physical characteristics — runs fast, looks muscular — that seem to go with being a ball player… the direct analog of “you are what you eat,” or the relative importance of lowering you cholesterol vs whether you actually live or die.

As early as the seventies, the computer had crunched baseball stats and come up with clear recommendations for strategy. The one I remember, since it was consistent with my own intuition, was that a sacrifice bunt was a poor play; sometimes it worked but you were much better off, statistically, having every batter simply try to get a hit. I remember my amazement at how little effect the computer results had on the frequency of sacrifice bunts in the game. Did science not count? What player or manager did not care whether you actually won or lost a baseball game. The themes that are played out in Moneyball, is that tradition dies hard and we don’t like to change our mind even for our own benefit. We invent ways to justify our stubbornness and we focus on superficial indicators rather than real performance and sometimes we are just not real smart.

Among the old ideas, still current, was that the batting average is the main indicator of a batter’s strength. The batting average is computed by considering that a base-on-balls is not an official at bat whereas a moments thought tells you that the ability to avoid bad pitches is an essential part of the batter’s skill. Early on, even before he was hired by Billy Beane, Paul DePodesta had run the statistics from every twentieth century baseball team. There were only two offensive statistics that were important for a winning team percentage: on-base percentage (which included walks) and slugging percentage. “Everything else was far less important.” These numbers are now part of baseball although I am not enough of a fan to know the extent to which they are still secondary to the batting average.

One of the early examples of the conflict between tradition and science was the scouts refusal to follow up on the computer’s recommendation to look at a fat, college kid named Kevin Youkilis who would soon have the second highest on-base percentage after Barry Bonds. “To Paul, he’d become Euclis: the Greek god of walks.”

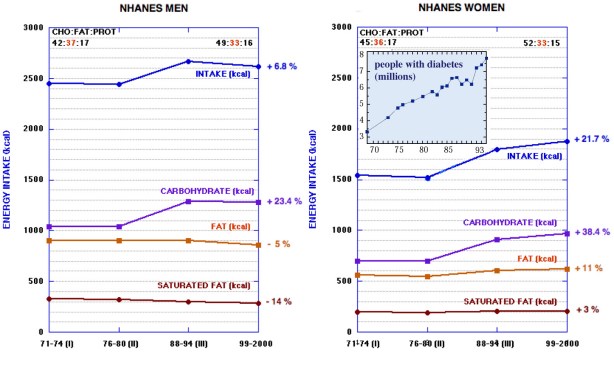

The big question in nutrition is how the cholesterol-diet-heart paradigm can persist in the face of the consistent failures of experimental and clinical trials to provide support. The story of these failures and the usurpation of the general field by idealogues has been told many times. Gary Taubes’s Good Calories, Bad Calories is the most compelling and, as I pointed out in a previous post, there seems to have been only one rebuttal, Steinberg’s Cholesterol Wars. The Skeptics vs. the Preponderance of Evidence. At least within the past ten year, a small group have tried to introduce new ideas, in particular that it is excessive consumption of dietary carbohydrate, not dietary fat, that is the metabolic component of the problems in obesity, diabetes and heart disease and have provided extensive, if generally un-referenced, experimental support. An analogous group tried to influence baseball in the years before Billy Beane. Larry Lucchino, an executive of the San Diego Padres described the group in baseball as being perceived as something of a cult and therefore easily dismissed. “There was a profusion of new knowledge and it was ignored.” As described in Moneyball “you didn’t have to look at big-league baseball very closely to see its fierce unwillingness to rethink any it was as if it had been inoculated against outside ideas.”

“Grady Fuson, the A’s soon to be former head of scouting, had taken a high school pitcher named Jeremy Bonderman and the kid had a 94 mile-per-hour fastball, a clean delivery, and a body that looked as if it had been created to wear a baseball uniform. He was, in short, precisely the kind of pitcher Billy thought he had trained the scouting department to avoid…. Taking a high school pitcher in the first round — and spending 1.2 million bucks to sign — that was exactly this sort of thing that happened when you let scouts have their way. It defied the odds; it defied reason. Reason, even science, was what Billy Beane was intent on bringing to baseball.”

The analogy is to the deeply ingrained nutritional tradition, the continued insistence on cholesterol and dietary fat that are assumed to have evolved in human history in order to cause heart disease. The analogy is the persistence of the lipophobes, in the face of scientific results showing, at every turn, that these were bad ideas, that, in fact, dietary saturated fat does not cause heart disease. It leads, in the end, to things like Steinberg’s description of the Multiple risk factor intervention trial. (MRFIT; It’s better not to be too clever on acronyms lest the study really bombs out): “Mortality from CHD was 17.9 deaths per 1,000 in the [intervention] group and 19.3 per 1,000 in the [control] group, a statistically nonsignificant difference of 7.1%”). Steinberg’s take on MRFIT:

“The study failed to show a significant decrease in coronary heart disease and is often cited as a negative study that challenges the validity of the lipid hypothesis. However, the difference in cholesterol level between the controls and those on the lipid lowering die was only about 2 per cent. This was clearly not a meaningful test of the lipid hypothesis.”

In other words, cholesterol is more important than outcome or at least a “diet designed to lower cholesterol levels, along with advice to stop smoking and advice on exercise” may still be a good thing.

Similarly, the Framingham study which found a strong association between cholesterol and heart disease found no effect of dietary fat, saturated fat or cholesterol on cardiovascular disease. Again, a marker for risk is more important than whether you get sick. “Scouts” who continued to look for superficial signs and ignore seemingly counter-intuitive conclusions from the computer still hold sway on the nutritional team.

“Grady had no way of knowing how much Billy disapproved of Grady’s most deeply ingrained attitude — that Billy had come to believe that baseball scouting was at roughly the same stage of development in the twenty-first century as professional medicine had been in the eighteenth.”

Professional medicine? Maybe not the best example.

What is going on here? Physicians, like all of us, are subject to many reinforcers but for humans power and control are usually predominant and, in medicine, that plays out most clearly in curing the patient. Defeating disease shines through even the most cynical analysis of physician’s motivations. And who doesn’t play baseball to win. “The game itself is a ruthless competition. Unless you’re very good, you don’t survive in it.”

Moneyball describes a “stark contrast between the field of play and the uneasy space just off it, where the executives in the Scouts make their livings.” For the latter, read the expert panels of the American Heat Association and the Dietary Guidelines committee, the Robert Eckels who don’t even want to study low carbohydrate diets (unless it can be done in their own laboratory with NIH money). In this

“space just off the field of play there really is no level of incompetence that won’t be tolerated. There are many reasons for this, but the big one is that baseball has structured itself less as a business and as a social club. The club includes not only the people who manage the team but also in a kind of women’s auxiliary many of the writers and commentators to follow and purport to explain. The club is selective, but the criteria for admission and retention and it is there many ways to embarrass the club, but being bad at your job isn’t one of them. The greatest offense a club member can commit is not ineptitude but disloyalty.”

The vast NIH-USDA-AHA social club does not tolerate dissent. And the media, WebMD, Heart.org and all the networks from ABCNews to Huffington Post will be there to support the club. The Huffington Post, who will be down on the President of the United States in a moment, will toe the mark when it comes to a low carbohydrate story.

The lessons from money ball are primarily in providing yet another precedent for human error, stubbornness and, possibly even stupidity, even in an area where the stakes are high. In other words, the nutrition mess is not in our imagination. The positive message is that there is, as they say in political science, validator satisfaction. Science must win out. The current threat is that the nutritional establishment is, as I describe it, slouching toward low-carb, doing small experiments, and easing into a position where they will say that they never were opposed to the therapeutic value of carbohydrate restriction. A threat because they will try to get their friends funded to repeat, poorly, studies that have already been done well. But that is another story, part of the strange story of Medicineball.