(Answers to last week’s organic puzzler at the end of this post).

One of the more remarkable results from Jeff Volek’s laboratory in the past few years was the demonstration that when the blood of volunteers was assayed for saturated fatty acids (SFA), those subjects who had been on a very low-carbohydrate diet had lower levels than those on an isocaloric low-fat diet. This, despite the fact that the low-carbohydrate diet had three times the amount of saturated fat as the low-fat diet. How is this possible? What happened to the saturated fat in the low-carbohydrate diet? Well, that’s what metabolism does. The saturated fat in the low-carbohydrate arm was oxidized while (the real impact of the study) the low-fat arm is making new saturated fatty acid. Volek’s former student Cassandra Forsythe extended the idea by showing how, even under eucaloric conditions (no weight loss) dietary fat has relatively small impact on plasma fat.

The essential point of what I now call the Volek-Westman principle — we should be speaking of basic principles because the idea is more important than specific diets where it is impossible to get any agreement on definitions — the principle is that carbohydrate, directly or indirectly through insulin and other hormones, controls what happens to ingested (or stored) fatty acids. The motto of the Nutrition & Metabolism Society is: “A high fat diet in the presence of carbohydrate is different than a high fat diet in the presence of low carbohydrate.” Widely attributed to me, it is almost certainly something I once said although it has been said by others and the studies from Volek’s lab give you the most telling evidence.

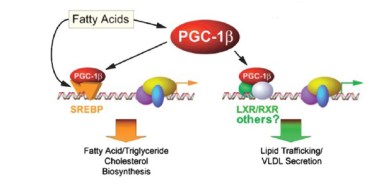

The question is critical. Whereas the scientific evidence now establishes that dietary saturated fat has no effect on cardiovascular disease, obesity or anything else, plasma saturated fatty acids can be a cellular signal and if you study the effect of dietary saturated fatty acids under conditions where carbohydrate is high and/or in rodents where plasma fat better correlates with dietary fat, then you will confuse plasma fat with dietary fat. An important study identified potential cellular elements in control of gene transcription that bear on lipid metabolism.

The question is critical. Whereas the scientific evidence now establishes that dietary saturated fat has no effect on cardiovascular disease, obesity or anything else, plasma saturated fatty acids can be a cellular signal and if you study the effect of dietary saturated fatty acids under conditions where carbohydrate is high and/or in rodents where plasma fat better correlates with dietary fat, then you will confuse plasma fat with dietary fat. An important study identified potential cellular elements in control of gene transcription that bear on lipid metabolism.

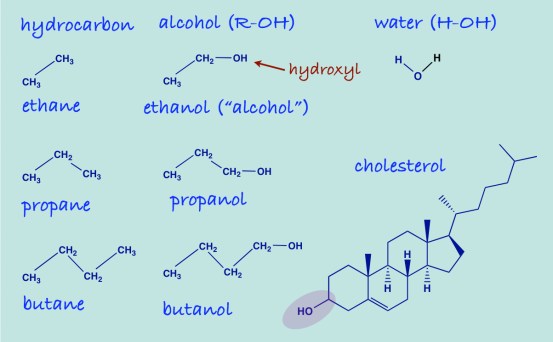

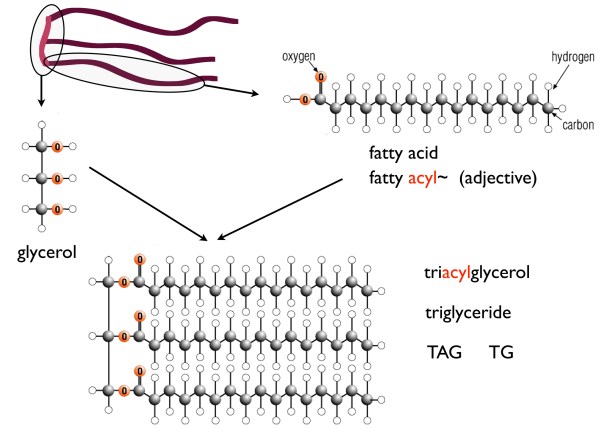

So, it is important to know about plasma saturated fatty acids. First, recall that strictly speaking there are only saturated fatty acids (SFA) — this is explained in detail in an earlier post. What is called saturated fats simply mean those fats that have a high percentage of SFAs — things that we identify as “saturated fats,” like butter, are usually only 50 % saturated fatty acids (coconut oil is probably the only fat that is almost entirely saturated fatty acids but because they are medium chain length, they are usually considered a special case).

In Volek’s study, 40 overweight subjects were randomly assigned either to a carbohydrate-restricted diet (abbreviated CRD; %CHO:fat:protein = 12:59:28) or to a low fat diet, (LFD; %CHO:fat:protein = 56:24:20). The group was unusual in that they were all overweight would be characterized as having metabolic syndrome, in particular they all had, atherogenic dyslipidemia, which is the term given to a poor lipid profile (high triacylglycerol (TAG), low HDL-C, high small-dense LDL (so-called pattern B)). Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is the predisposition to CVD and diabetes and is characterized by the constellation of overweight, atherogenic dyslipidemia and, by now, a dozen other markers.

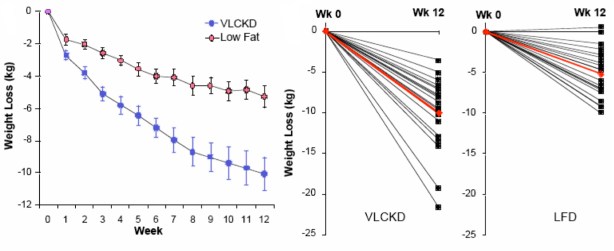

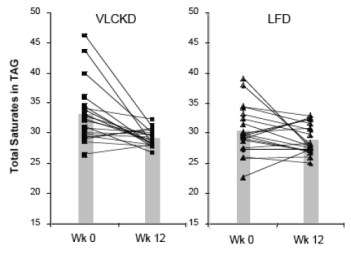

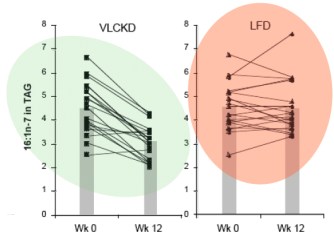

The paper is one of the more striking for the differences in weight loss between two diet regimens. Although participants were not specifically counseled to reduce calories, there was a reduction in total caloric intake in both two groups. The response in weight loss, however, due to the difference in macronutrient composition, was dramatically different in the two groups. The CRD group (labelled as very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet (VLCKD) in the figure) lost twice as much weight on average as the low-fat controls despite the similar caloric intake. Although there was substantial individual variation, 9 of 20 subjects in the CRD (VLCKD) group lost 10% of their starting weight. more than that lost by any of the subjects in the LFD group. In fact, nobody following the LFD lost as much weight as the average for the low-carbohydrate group and, unlike George Bray’s demonstration of caloric inefficiency, whole body fat mass was where the major differences between the CRD (VLCKD) and LF appeared (5.7 kg vs 3.7 kg). Of significance is the observation that fat mass in the abdominal region decreased more in subjects on the CRD than in subjects following the LFD (-828 g vs -506 g). This is one of the more dramatic effects of carbohydrate restriction on weight loss but many have preceded it and these have been frequently criticized for increasing the amount of saturated fat (whether or not any particular study actually increased saturated fat). Although the original “concern” was that this would lead to increased plasma cholesterol, eventually saturated fat became a generalized villain and, insofar as any science was involved, the effects of plasma saturated fat were assumed to be due to dietary saturated fat. The outcome of Volek’s study was surprising. Surprising because the effect was so clear cut (no statistics needed) and because an underlying mechanism could explain the results.

Saturated Fat

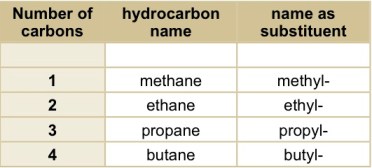

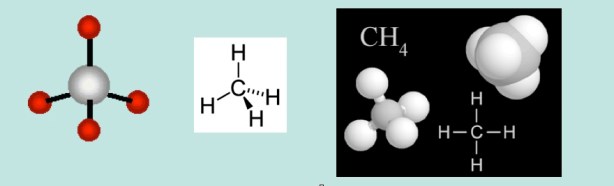

The dietary intake of saturated fat for the people on the VLCKD (36 g/day) was threefold higher than that of the people on the LFD (12 g/day). When the relative proportions of circulating SFAs in the triglyceride and cholesterol ester fractions were determined, they were actually lower in the low carb group. Seventeen of 20 subjects on the CRD (VLCKD) showed a decrease in total saturates (the others had low values at baseline) in comparison to half of the subjects consuming the LFD had a decrease in saturates. When the absolute fasting TAG levels are taken into account (low carbohydrate diets reliably reduce TAB=G), the absolute concentration of total saturates in plasma TAG was reduced by 57% in the low carbohydrate arm compared to 24% reduction in the low fat arm who had, in fact, reduced their saturated fat intake. One of the saturated fatty acids of greatest interest was palmitic acid or, in chemical short-hand, 16:0 (16 means that there are 16 carbons and 0 means there are no double bonds, that is, no unsaturation).

The dietary intake of saturated fat for the people on the VLCKD (36 g/day) was threefold higher than that of the people on the LFD (12 g/day). When the relative proportions of circulating SFAs in the triglyceride and cholesterol ester fractions were determined, they were actually lower in the low carb group. Seventeen of 20 subjects on the CRD (VLCKD) showed a decrease in total saturates (the others had low values at baseline) in comparison to half of the subjects consuming the LFD had a decrease in saturates. When the absolute fasting TAG levels are taken into account (low carbohydrate diets reliably reduce TAB=G), the absolute concentration of total saturates in plasma TAG was reduced by 57% in the low carbohydrate arm compared to 24% reduction in the low fat arm who had, in fact, reduced their saturated fat intake. One of the saturated fatty acids of greatest interest was palmitic acid or, in chemical short-hand, 16:0 (16 means that there are 16 carbons and 0 means there are no double bonds, that is, no unsaturation).

So how could this happen? The low fat group reduced their SFA intake by one-third, yet had more SFA in their blood than the low-carbohydrate group who had actually increased intake. Well, we need to look at the next thing in metabolism.

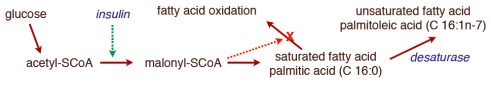

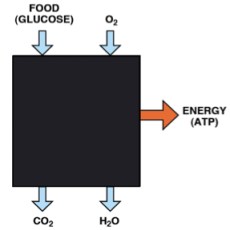

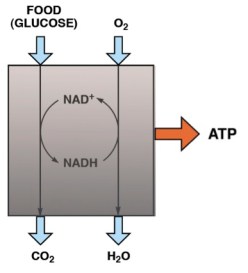

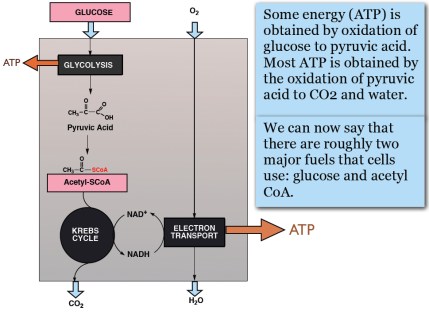

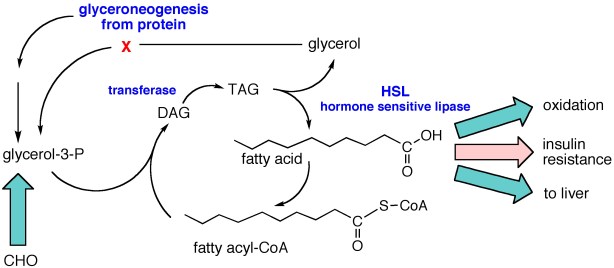

In the post on An Introduction to Metabolism, we made the generalization that there were roughly two kinds of fuel, glucose and acetyl-CoA (the two carbon derivative of acetic acid). The big principle in metabolism was that you could make acetyl-CoA from glucose, but (with some exceptions) you couldn’t make glucose from acetyl-CoA, or more generally, you can make fat from glucose but you can’t make glucose from fat. How do you make fat from glucose? Part of the picture is making new fatty acids, the process known as De Novo Lipogenesis (DNL) or more accurately de novo fatty acid synthesis. The mechanism then involves successively patching together two carbon acetyl-CoA units until you reach the chain length of 16 carbons, palmitic acid. The first step is formation of a three carbon compound, malonyl-CoA, a process which is under the control of insulin. Malonyl-CoA starts the process of DNL but simultaneously prevents oxidation of any fatty acid since, if you are making it, you don’t want to burn it. This can be further processed, among other things, can be elongated to stearic acid (18:0). So this is a reasonable explanation for the increased saturated fatty acid in the low-fat group: the higher carbohydrate diet has higher insulin levels on average, encouraging diversion of calories into fatty acid synthesis and repressing oxidation. How could this be tested?

It turns out that, in addition to elongation, the palmitic acid can be desaturated to make the unsaturated fatty acid, palmitoleic acid (16:1-n7, 16 carbons, one unsaturation at carbon 7) and the same enzyme that catalyzes this reaction will convert stearic acid (18:0) to the unsaturated fatty acid oleic acid (18:1n-7). The enzyme is named for the second reaction stearoyl desaturase-1 (SCD-1; medical students always hate seeing a “-1” since they know 2 and 3 may will have to be learned although, in this case, they are less important). SCD-1 is a membrane-bound enzyme and it seems that it is not swimming around the cell looking for fatty acids but is, rather, closely tied to DNL, that is, it preferentially de-saturates newly formed palmitic acid to palmitoleic acid.

It turns out that, in addition to elongation, the palmitic acid can be desaturated to make the unsaturated fatty acid, palmitoleic acid (16:1-n7, 16 carbons, one unsaturation at carbon 7) and the same enzyme that catalyzes this reaction will convert stearic acid (18:0) to the unsaturated fatty acid oleic acid (18:1n-7). The enzyme is named for the second reaction stearoyl desaturase-1 (SCD-1; medical students always hate seeing a “-1” since they know 2 and 3 may will have to be learned although, in this case, they are less important). SCD-1 is a membrane-bound enzyme and it seems that it is not swimming around the cell looking for fatty acids but is, rather, closely tied to DNL, that is, it preferentially de-saturates newly formed palmitic acid to palmitoleic acid.

There is very little palmitoleic acid in the diet so its presence in the blood is an indication of SCD-1 activity. The data show a 31% decrease in palmitoleic acid (16:1n-7) in the blood of subjects on the low-carb arm with little overall change in the average response in the low fat group. Saturated fat, in your blood or on your plate?

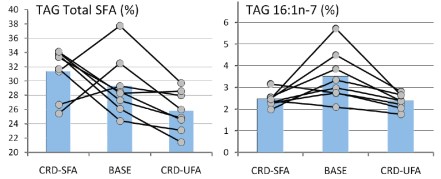

Forsythe’s paper extended the work by putting men on two different weight-maintaining low-carbohydrate diets for 6 weeks. One of the diets was designed to be high in SFA (high in dairy fat and eggs), and the other, was designed to be higher in unsaturated fat from both polyunsaturated (PUFA) and monounsaturated (MUFA) fatty acids (high in fish, nuts, omega-3 enriched eggs, and olive oil). The relative percentages of SFA:MUFA: PUFA were, for the SFA-carbohydrate-restricted diet, 31: 21:5, and for the UFA diet, 17:25:15. The results showed that the major changes in plasma SFA and MUFA were in the plasma TAG fraction although probably much less than might be expected given the nearly two-fold difference in dietary saturated fat and, as the authors point out: “the most striking finding was the lack of association between dietary SFA intake and plasma SFA concentrations.”

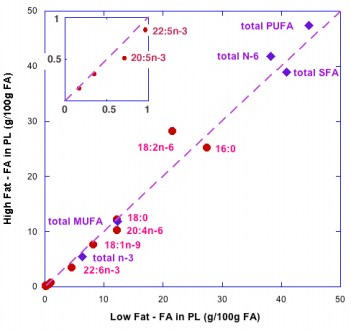

So although it is widely said that the type of fat is more important than the amount, the type is not particularly important. But, what about the amount? A widely cited paper by Raatz, et al. suggested, as indicated by the title, that ‘‘Total fat intake modifies plasma fatty acid composition in humans”, but the data in the paper shows that differences between high fat and low fat were in fact minimal (figure below).

So although it is widely said that the type of fat is more important than the amount, the type is not particularly important. But, what about the amount? A widely cited paper by Raatz, et al. suggested, as indicated by the title, that ‘‘Total fat intake modifies plasma fatty acid composition in humans”, but the data in the paper shows that differences between high fat and low fat were in fact minimal (figure below).

The bottom line is that distribution of types of fatty acid in plasma is more dependent on the level of carbohydrate then the level or type of fat. Volek and Forsythe give you a good reason to focus on the carbohydrate content of your diet. What about the type of carbohydrate? In other words, is glycemic index important? Is fructose as bad as they say? We will look at that in a future post in which I will conclude that no change in the type of carbohydrate will ever have the same kind of effect as replacing carbohydrate across the board with fat. I’ll prove it.

====================================================================

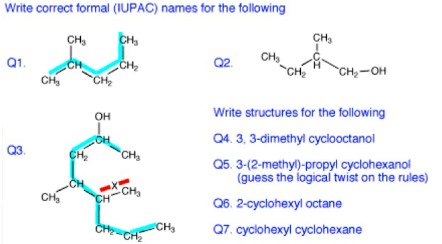

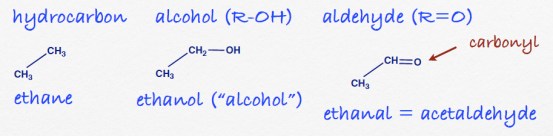

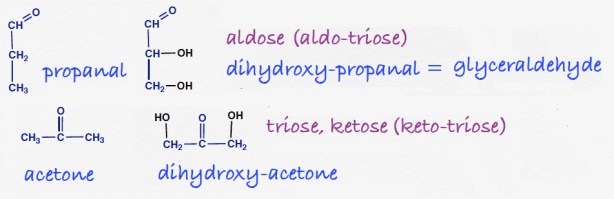

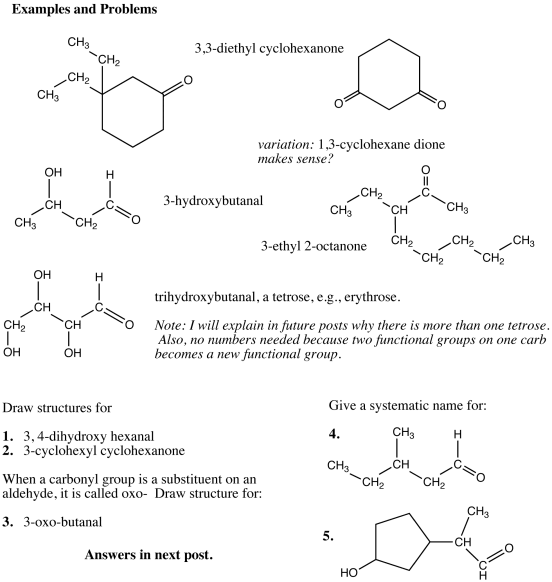

Answers to the organic quiz.